Dinger's Aviation Pages

A short overview of British aircraft weapons of WWII.

There are some excellent online references that go into great detail about individual weapons (see a list of links at the foot of the page). However, I felt there was a need for a simpler, short overview that put the weapons into some historical context. Here is the result.

The Gloster Gladiator preserved at the Shuttleworth Collection. When first introduced, the Gladiator had two Vickers guns in the fuselage and a Lewis gun in the blisters under each wing. The Vickers guns were later replaced by Brownings and the Lewis guns by Vickers "K" guns. Then the Vickers "K"s were themselves replaced by Brownings, giving the Gladiator an armament of four Browning machine guns.

In the forground is the muzzle of the .303 Browning machine gun protruding from the blister under the wing of the Gloster Gladiator. Behind, firing through a channel in the side of the fuselage and then through the inside of the Townsend Ring surrounding the engine is another Browning. The fuselage Brownings were synchronised to be able to fire through the propeller disk.

There are some excellent online references that go into great detail about individual weapons (see a list of links at the foot of the page). However, I felt there was a need for a simpler, short overview that put the weapons into some historical context. Here is the result.

The Gloster Gladiator preserved at the Shuttleworth Collection. When first introduced, the Gladiator had two Vickers guns in the fuselage and a Lewis gun in the blisters under each wing. The Vickers guns were later replaced by Brownings and the Lewis guns by Vickers "K" guns. Then the Vickers "K"s were themselves replaced by Brownings, giving the Gladiator an armament of four Browning machine guns.

In the forground is the muzzle of the .303 Browning machine gun protruding from the blister under the wing of the Gloster Gladiator. Behind, firing through a channel in the side of the fuselage and then through the inside of the Townsend Ring surrounding the engine is another Browning. The fuselage Brownings were synchronised to be able to fire through the propeller disk.

At the end of the First World War, the Royal Air Force was using an air-cooled variant of the belt-fed Vickers machine gun and the Mark III version of the Lewis drum-fed machine gun. The Vickers gun was used in installations where the gun had to fire through the spinning propeller, its closed-bolt system being compatible with the synchronisation system that entailed. The rate of fire of the aircraft Vickers gun was increased to nearly double that of the infantry gun by the addition of a "muzzle booster" (invented by Lt Cdr George Hazelton RN). The Vickers gun came in two versions, the most common one firing the standard British .303 calibre rounds and another, available in only limited numbers, built by Colt in the USA that fired larger French 11mm rounds that were used for "balloon bursting" (shooting down enemy observation balloons). The Lewis gun fired from an open bolt and was unable to be used with synchronisation gear so it was most often used on movable mounts by observers and dedicated gunners or was fixed to fire outside the arc of the propeller. One method that allowed a pilot to use a Lewis gun was the "Foster mount", where the gun was mounted on top of the wing but could be slid back on a rail until it was vertical. The British had developed a series of incendiary bullets to bring down Zeppelin airships and observation balloons. The most common was the "Buckingham", which also had a tracer effect, leaving a smoke trail behind it.

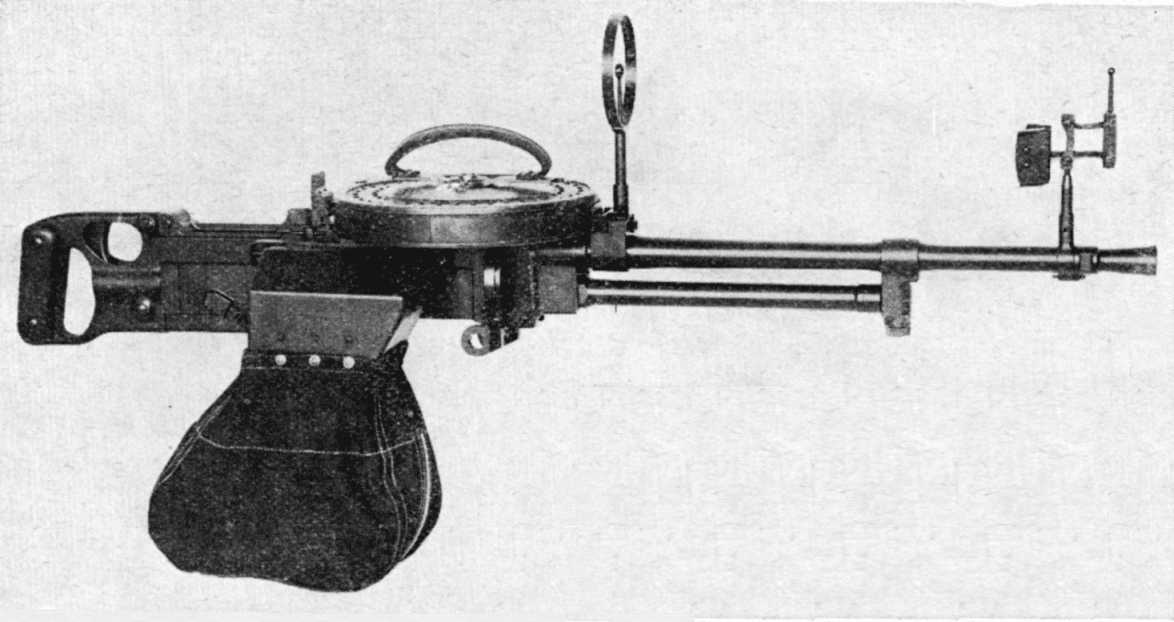

The Lewis gun, as used on aircraft during WW1. Note the pistol grip and the bag to hold spent cartridges. The large, ridged magazine could hold up to 100 rounds (Usually only 96 were loaded to avoid stoppages caused by the magazine spring being over-compressed). This example has a "muzzle booster" on the end of the barrel to increase the rate of fire. The Mark III gun, introduced in 1918, did away with the booster, achieving an increased rate of fire without it.

The rear gun position of a Vickers Wellesley showing a Mk III Lewis gun with magazine fitted. By the start of WW2, the Lewis gun had been replaced by the Vickers "K" gun in RAF service in the UK and Northern Europe but it continued to be used in the Middle and Far East and by the Royal Navy.

The rear gun position of a Vickers Wellesley showing a Mk III Lewis gun with magazine fitted. By the start of WW2, the Lewis gun had been replaced by the Vickers "K" gun in RAF service in the UK and Northern Europe but it continued to be used in the Middle and Far East and by the Royal Navy.

This combination of the Vickers and the Lewis saw the RAF through the 1920s and into the mid-1930s. In the early 1930s the need for increased fire-power to bring down larger aircraft, built primarily of metal, was recognised. A first step in this direction was the mounting of Lewis guns in the wings of some prototype British aircraft in the 1930s and their adoption for use mounted in blisters below the wings of the Gladiator fighter. Meanwhile, trials led to the adoption of a variant of the American 0.30 M1919 Browning machine gun as the fixed machine gun for the next generation of British fighters. This was slightly lighter than the Vickers and had a much greater rate-of-fire. It was recognised that batteries of at least 6, (then increased to 8)¹ of these guns would be required (some marks of Hurricane could mount up to 12 guns). Built in the UK by BSA (Birmingham Small Arms), the Browning was redesigned for British use, changing to .303 calibre and being altered to fire from an open bolt to avoid "cook-offs" (something that the cordite-filled British rounds were more prone to than the nitrocellulose US .30 rounds). Using an open bolt would normally preclude a guns use with synchronisation gear, but the British Browning could use a mechanism that closed the bolt when the trigger was pulled but only fired the round when the synchronisation gear engaged. In the event, this was only put to use in late production Gladiator biplane fighters (early ones used the older Vickers gun) and in RAF Brewster Buffalos converted to use them instead of .50 Brownings. All other British fighters that used the gun had them fitted in the wings to fire outside the propeller arc.² The Browning was also used in the new enclosed turrets for the next generation of British bombers, the Wellington and Whitley (along with the Defiant turret fighter), with up to four guns in some turrets. The old Vickers gun was still in use in older designs, such as the Fairey Swordfish, into the Second World War. Australian Wirraway two-seat army support aircraft were still fitted with them at the end of the war in the Pacific.

Browning .303 machine gun, in the care of the Spitfire Society, on display at the Sywell Airshow in 2024.

The Lewis gun was replaced by a new drum-fed design from Vickers called the Vickers "K" gun, also known as the "VGO" (Vickers Gas Operated). This had a higher rate of fire than the old Lewis gun, was more reliable, and if stoppages did occur they were much easier to clear. The Vickers K fired from an open bolt and so could not be used with synchronisation gear. It was used primarily as a moveable machine gun for observers and gunners although the turrets of the Avro Anson, Bristol Bombay, HP Harrow and early Bristol Blenheim bombers also mounted them. At the outbreak of World War Two, the RAF was switching from the Lewis to the Vickers K and it was rare for the earlier Lewis to be used in combat by the RAF in Northern Europe (some were still used on Wellesley bombers and older biplane types operating in East Africa). However, the Royal Navy retained the Lewis gun for use until the end of 1940.³

Vickers "K" or "VGO" gun; note there is no pistol grip, instead the trigger is built into the spade grip. This picture shows the slim, smooth-sided, 60-round magazine. In service, the larger 100-round magazine would have been more commonly used (again, only loaded with 96 rounds to avoid stoppages). This example has a ring-and-bead back sight with a forward Norman vane sight that helped with deflection shooting. The bag below the gun collected spent cartridge cases. The Vickers K had a higher rate of fire than the earlier Lewis and was less prone to stoppages. It was used extensively by the RAF for the first two years of World War Two. It was coveted by gunners on Royal Navy aircraft such as the Swordfish and Skua because the Royal Navy did not adopt it until the end of 1940.

Early experience in World War Two showed that the need to change the magazine on the Vickers K when under sustained attack was a big drawback, so wherever space permitted a belt-fed Browning was substituted, indeed where possible a pair of Brownings were used instead. The Hampden and the Lysander were two aircraft so upgraded. The turret of the Blenheim was also redesigned to accommodate two Brownings instead of the single "K" gun. Many of the Vickers "K" guns were then passed on to Commando units, the Parachute Regiment and the SAS. Some were even used by the American Rangers that seized the German gun battery at Pointe Du Hoc on D-Day.

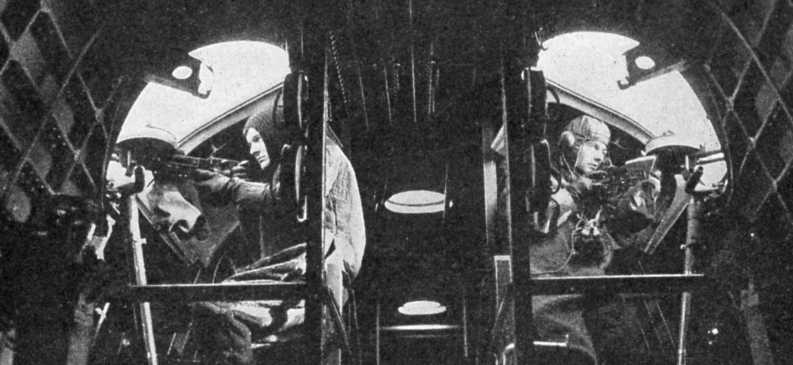

The two mid-upper gunners of a Short Sunderland flying boat, equipped with Vickers "K" guns.

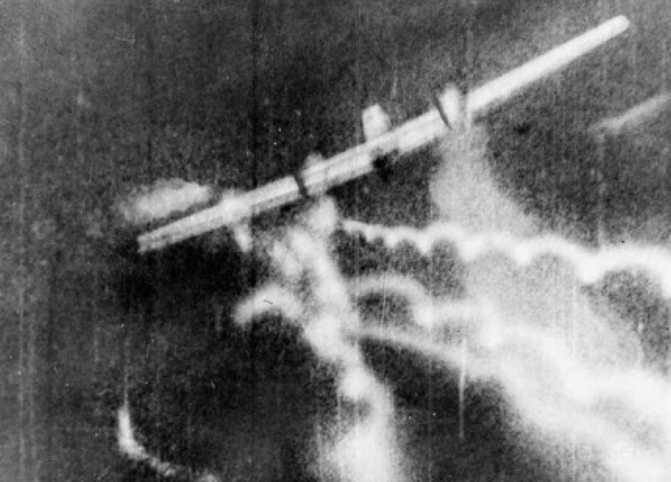

All these British machine guns used a combination of normal "ball", tracer and armour-piercing rounds (the latter only of use against thin armour). The lethality of the British guns was greatly increased by the introduction of "de Wilde" incendiary rounds. These had been developed in secret at Woolwich Arsenal and were only just ready in time for the Battle of Britain. They were much more effective than the old Buckingham rounds in setting fire to ruptured fuel tanks. Named "de Wilde" ammunition by the British this was a ruse to make the Germans think it was based on the work of a Mr de Wilde (a Belgian living in Switzerland). In fact, it had been found that "proper" de Wilde bullets could only be made by hand, whereas the British design could be mass-produced by machine. The British "de Wilde" bullets were the invention of C. Aubrey Dixon, a Captain in the Bedfordshire and Hertfordshire Regiment (he retired with the rank of Brigadier). The "de Wilde" ammunition produced a small explosion that would ignite anything flammable being particularly effective against fuel tanks. The speckles of light it produced when hitting its target confirmed that a pilot's aim was true. During the Battle of Britain, supplies of "de Wilde" were low, so it was supplemented by the older Buckingham incendiary/tracer rounds. The Buckingham rounds left a smoke trail behind them, these spiral trails were often captured on gun-camera footage. As the war progressed the Buckingham rounds were used less and less, replaced by the more deadly "de Wilde" type.

Gun-camera still of a Messerschmitt Me110 under attack, showing the spiral smoke trails left by the old WWI design "Buckingham" incendiary/tracer rounds.

Spitfires and Hurricanes in the Battle of Britain carried 350 rounds for each Browning gun which gave only 18 seconds of firing time. The Royal Navy's Skua and Fulmar carried 600 rounds per gun which gave 31 seconds firing time. The Defiant's turret guns also used belts of 600 rounds. British pilots and gunners were taught to count the seconds of each burst of machine-gun fire to keep track of how much ammunition they had left, unlike German pilots who had ammunition counter gauges in the cockpit. It should be noted that none of these machine guns were designed to fire very long bursts of fire, they would overheat and risk damage. Bursts of 2-3 seconds were the norm with bursts longer than 6 seconds only in exceptional circumstances. During the early night blitz on the UK, the gunner in the turret of a Blenheim night fighter was surprised when the pitch black of the night sky was suddenly illuminated by the cockpit lights of a Heinkel 111 bomber that appeared out of clouds directly above him. He poured the entire contents of the 96 round drum magazine of his Vickers K gun into the cockpit of the bomber, causing it to crash to earth, but overheating his gun in the process. Night victories were rare at this stage of the war so the crew were feted when they landed. The celebration was cut short when one of the station armourers appeared brandishing the damaged barrel of the Vickers K gun and demanding the arrest of the gunner for damaging government property! ⁴

At the start of WW2, Britain was not alone in fielding rifle calibre guns in its aircraft, most of the major powers used them but increasingly the Germans, French, Russians and Dutch were supplementing them with the new cannon designs (although as many as a third of the German Messerschmitt Bf109s used in the Battle of Britain still had only machine guns for armament). What was not appreciated at the time was that the ShKAS rifle-calibre guns adopted by the Soviet Union were able to fire at twice the rate of the other nations guns (1,800 rounds per minute) while it still weighed about the same. Thus one ShKAS gun would have been worth two Browning .303 machine guns. However, its design was complicated and that complication could lead to jamming if not maintained properly or if there were inconsistencies in the ammunition used (the ammunition for the gun was specially made to a high standard).

Many of the US aircraft supplied to Britain came with the .50 calibre Browning. This large calibre gun had a longer range and the projectile did much more damage. However, it did weigh considerably more and had a lower rate of fire (a post-war development of the .50 did have a higher rate of fire). Some late-war Spitfires used a pair of .50 Brownings alongside 20 mm cannon. The .50 calibre Browning served the Americans well, providing their needs for both fighters and bombers throughout WW2 and even into the Korean war (the gun is still in widespread use today). These days there is a lot of online criticism of the British for not adopting the .50 Browning in place of the .303 before the war started. There are a few factors to take into consideration. Firstly, at the time that the .303 Browning was adopted (the early to mid-1930s) the prime consideration in British thinking was volume of fire, penetration and range were seen as secondary. The Air Ministry had a preoccupation with the brevity of modern aerial combat and the need to score as many hits in the minimum time was seen as paramount. It was only later that armour and self-sealing tanks became commonplace on military aircraft. Secondly, if they had considered a move to .50 calibre in the mid-1930s the British Vickers company already produced their own .50 calibre gun which they were trying to sell to foreign air forces. This gun had already been adopted by both the British Navy and Army. The Navy used it on quad mountings for anti-aircraft defence and the Army used it in light tanks and the Matilda I infantry tank. The Army and Navy had only adopted it after comparative tests with an early example of the American Browning .50 gun, in which the Vickers was deemed to be the better design. So if the RAF was going to adopt a .50 machine gun it is likely to have been the Vickers. This would have been a disaster, the Vickers .50 round was much less powerful than the American round resulting in a shorter range and less penetration. In service with the Navy and Army, it proved a troublesome, unreliable weapon and was soon abandoned by both services. The Vickers .50 round did give Britain one great service however, the Italians adopted it for their SAFAT and Scotti machine guns with a small explosive charge, where its lack of range and penetration no doubt saved many an Allied life! On top of that, the Japanese Army, in turn, adopted the same size of round with a small explosive charge for their Ho-103 machine gun which in all other respects was a copy of the Browning .50 gun. Thus again the reduced penetration and range made it inferior to the US original.⁵ As it was, when the British first received aircraft from the USA fitted with the Browning .50 there were problems with its ammunition. The cartridges on armour piercing rounds would split causing guns to jam, tracer rounds were in short supply and when used would damage the gun barrels. Finally, there was no .50 equivalent to the de Wilde round. Such was the frustration that some of the Brewster Buffalo fighters in the Far East were converted to use the rifle-calibre .303 Brownings. All the issues with the .50 calibre were resolved but by then it was too late for the RAF Brewster Buffalo pilots in Malaya and Singapore.⁶

Comparison of the sizes of a .50 bullet (top) and a .303 Bullet (bottom) from a display at the excellent City of Norwich Aviation Museum.

It turns out that there were earlier plans by the RAF to adopt a version of the Browning .50 gun. When the war started in 1939, there was a push to start standardising the equipment and production of the British and French air forces. It was decided that both should adopt the Belgian FN version of the big Browning machine gun with the manufacture of the type to be set up in both Britain and France. The FN version of the Browning had been slightly redesigned for a faster rate of fire and a slightly larger calibre (13.22 mm) to allow it to fire explosive shells, effectively making it a "cannon".⁷ During the invasion of Belgium in 1940, key personnel from FN were evacuated to the UK with hope of keeping the project alive, but it was easier to just accelerate production of the existing .303 Browning and await the availability of the 20mm Hispano.

Rolls Royce also developed a .50 calibre machine gun, hoping it would be adopted by the RAF. Testing threw up numerous problems and the project was halted in 1942. Another interesting side-note is that Vickers developed a .50 calibre round that was much more powerful than even the American Browning round. Meant to be used in their large "Commercial Mark D" water-cooled machine gun. It was seen primarily as an anti-aircraft weapon. Details of the round can be seen in this YouTube video by the Vickers MG Collection & Research Association. The Vickers D did not see service with British forces, although early in WW2 a couple were mounted on a light tank chassis as a prototype of a proposed anti-aircraft tank.

The four 20mm Hispano cannon with 60-round drum magazines mounted in the nose of a Westland Whirlwind fighter. Except for some trial experiments, the Whirlwind retained the drum magazines throughout its service career and never had the advantage of the longer firing time afforded by belt-fed ammunition.

As early as 1935, some 4 years before the Second World War started, the British had realised that the .303 calibre was going to be inadequate and started issuing specifications for fighter aircraft to be armed with the Hispano 20 mm cannon, and a quartet of these weapons became the standard weapons fit for all late-war British fighter designs. The slower rate of fire of the cannon was offset by their much-increased range and lethality. However, the Hispano's introduction into service was blighted by problems with its ammunition drum feed systems, which meant it did not start to produce consistently good results until the spring of 1941. No 19 Squadron flew cannon-armed Spitfires for a while during the Battle of Britain but flexing of the wing caused jams, and the squadron quickly returned to using machine guns. A couple of Hurricanes, one with a pair of cannons and another with four cannons, also saw service during the Battle of Britain, with better results, claiming some kills. When first used, the Hispano cannon used drums containing 60 rounds giving only 5 seconds of firing time. It was this early drum mechanism that often jammed in service but was later improved. Spitfires with the "B" wing, with a 20 mm gun with 60-round drum magazines, began to be used from November 1940. A belt feed mechanism was developed, copied from the French "Châtellerault" system, which was significantly more reliable and was typically used with belts of 120 rounds, providing a 10-seconds firing time (cannon-armed Hurricanes Mk IICs used belts with 91 rounds, resulting in a 7 to 8-seconds firing time). Spitfires with the "C" wing began to use the belt-feed mechanism from October 1941. The later de Havilland Mosquito, Hawker Typhoon, Tempest and Gloster Meteor also used the belt-feed system. The Bristol Beaufighter started off with drum magazines but switched to the Châtellerault system. The Westland Whirlwind fighter kept the drum magazines for its service career although one of them was experimentally fitted with the abortive "Hydran" pneumatic worm-drive ammunition feed system. In 1942, the Martin Baker company developed a superior "flat feed" ammunition belt system for their own MB3 six-cannon fighter prototype and this began to be used on other aircraft later in the war and went on to find widespread use post-war. The Hispano cannon's explosive shells would do extensive damage to aircraft structures. However, towards the end of the war, it was found that solid armour-piercing rounds were producing better results against the types of targets then being engaged, better-armoured German aircraft and ground vehicles.

A display of weapons at the Newark Air Museum (UK). At the top, number 1 is the Browning .303 machine gun, below it, number 2 is the .50 calibre Browning machine gun. Number 3 is the Hispano 20 mm Cannon, and lastly Number 4 is the post-war 30mm Aden Cannon.

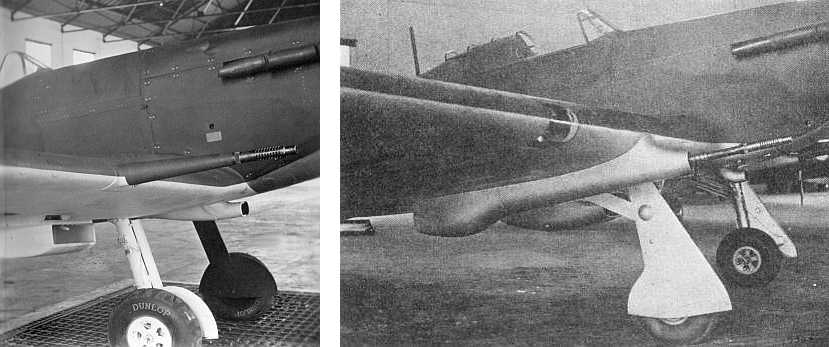

Two uses of 20mm cannon by the RAF during the Battle of Britain. On the left is one of the early installations into the wing of a Spitfire Mk I. They were used by No 19 Squadron, who did claim a few victories with them, but they were withdrawn because of constant jamming of the feed mechanism by flexing of the Spitfire's thin wing. On the right is the single Hurricane Mk I (L1750) fitted with 20mm cannons in "gondolas" beneath each wing. This was flown by Flt Lt Roddick Lee "Dick" Smith of 151 Squadron during June and August 1940, in which time he claimed a Bf109 and Do 17 "confirmed", a Bf109 "probable" and a Do 17 "damaged". Another experimental Mk I Hurricane, V7360, fitted with four cannons installed within the wings, was also flown by Flt Lt Smith in late August 1940, claiming a Bf109 "confirmed" and another "probable".

An informative video on the adoption of 20mm Cannons on the Spitfire can be found on the Fired Up! YouTube channel at <this link>.

In all the pre-war planning by the RAF for fighter armament one concept that kept repeating was that of "no-allowance sighting". You can read about this in the web page at the link below. As part of this concept, the RAF experimented with the large 37mm (1½ inches) cannon produced by the Coventry Ordnance Works (the so-called "COW" gun). It was used to fire upwards on a variety of experimental types and briefly used in service mounted in the bow position on the big Blackburn Perth flying boats.

In all the pre-war planning by the RAF for fighter armament one concept that kept repeating was that of "no-allowance sighting". You can read about this in the web page at the link below. As part of this concept, the RAF experimented with the large 37mm (1½ inches) cannon produced by the Coventry Ordnance Works (the so-called "COW" gun). It was used to fire upwards on a variety of experimental types and briefly used in service mounted in the bow position on the big Blackburn Perth flying boats.

<CLICK HERE TO READ ABOUT "NO-ALLOWANCE SIGHTING".>

The twin 40 mm Vickers "S" guns mounted under the wings of a Hurricane Mk IID in the Western Desert.

The COW gun was developed by Vickers into the 40mm "S" gun. First seen as a weapon for the defence of bombers (a turret for it was designed and tested on a Wellington bomber), it was later adopted as an anti-tank weapon, two being mounted under the wings of Hurricanes. It was used to great effect in the North African desert and the Far East. A gun with similar performance made by Rolls Royce was tested in a Beaufighter and Hurricane. It had problems coping with low temperatures and high "g" loads and was never adopted for use by the RAF, although it was used by the Royal Navy on Motor Gun Boats in the English Channel and Mediterranean. The ultimate heavy gun used by the RAF in WW2 was the 57mm "Molins Gun", an automatic version of the 6 pounder anti-tank gun used on the "Tsetse " version of the Mosquito.

The 57mm Molins gun installation in the "Tsetse" Mosquito showing the size of one of the rounds. Above it are a row of four Browning .303 machine guns.

It should be noted that in the 1920s and early 30s, with a background of international disarmament talks at the League of Nations, there was every chance that whole ranges of weapons would be banned. The use of explosive and incendiary rounds was a particular topic for debate. Indeed some interpretations of the St Petersburg Declaration of 1868 saw it as banning all such rounds under the size of 37 mm ⁸ (which is often cited as the reason for 37 and 40 mm being so prevalent for smaller calibre field pieces). So the use of explosive cannon shells of 20mm and explosive incendiary ammunition in rifle calibres could be viewed as illegal under international law. All parties seem to have just ignored the international legal ramifications of the new developments in armament once the rearmament of Germany was revealed by Hitler in 1935.

In the first months of the war, incursions by British Battle, Wellington and Hampden bombers met with heavy losses. It was realised that the defensive power of the .303 machine guns was inadequate against German Bf109 and Bf110 fighters. So the British largely switched to night bombing where the short range of the .303 was less of a disadvantage. Increasingly the gunners were seen to be there to give warning of German fighters to the pilot and the main defensive measure was the violent "corkscrew" the aircraft would enter into to escape, any German fighters shot down or damaged by the gunners were a welcome bonus.⁹ At this stage, the British did plan to return to the offensive in daytime, even before the war had started they had called on British industry to design turrets with four 20mm cannon in them, and the bomber designs to carry them (Air Ministry specification 1/39). This led to the Bristol 159 four-engined bomber armed with two of the four-cannon turrets (one dorsal, the other ventral). The Bristol 159 was one of the casualties of Lord Beaverbrook's decree that all production should be concentrated on existing types during the emergency period of 1940. American .50 calibre guns were in short supply to Britain and it was only in late 1944 that British built bombers started to use the "Rose" turret with twin .50 calibre guns. The Avro Lincoln bomber just coming into service at the end of the war was armed with a mixture of .50 Brownings (in tail and nose turrets) and 20mm cannon (in a dorsal turret). Some late versions of the Fairy Fulmar carrier fighter were fitted with four .50 browings in place of eight .303 guns.

Towards the end of the war, the Royal Navy's offensive fighters with the Pacific Fleet either used the American .50 machine guns (Hellcats and Corsairs) or 20 mm cannon (Fireflies). When the Fleet attacked the oil refineries in Japanese-held Sumatra (Operation Meridian) they were surprised to find they were defended by large numbers of barrage balloons. None of the incendiary ammunition available for these weapons had much effect on these balloons, so the attacking Avenger bombers had to thread their way through the balloon cables. Some pilots might have welcomed some .303 Brownings with old Buckingham incendiary rounds!

Table of RAF / FAA aircraft weapon specifications.

Best viewed on phones and tablets in "landscape" mode.

* The weight and rate of fire of the Mark III Lewis gun, adapted for aircraft use, was different to the standard infantry Lewis gun that is commonly quoted in descriptions in articles and websites.

** The Vickers K is sometimes listed as adjustable up to 1,200 rpm. My understanding is that this could only be done by the fitting of a non-standard gas-plug, something very unlikely to have been done in normal RAF service. The "No 4" version of the Vickers K, intended for use in armoured cars, had the rate of fire adjusted down to 700 rpm to conserve ammunition.

Weight of fire of 3-second burst from various marks of Spitfire and contemporary German fighters.

Duration of Fire - A Neglected Topic?

Discussions on the merits of different aircraft armament always seem to centre on the weight of fire of weapons, with a secondary consideration being the range. What is seldom considered is the duration of fire different aircraft could achieve (the amount of ammunition they carried and how long it lasted). While looking up details of different aircraft it is always possible to see what type of machine guns and cannons they carried, but it is much more difficult to find out the ammunition capacity (particularly for the less well-known fighter types).

It may seem a trite observation, to compare the life-and-death struggle of WW2 pilots with the experience of modern combat flight-sim players, but, as an avid flight-sim player once remarked to me, "The first cheat you enable is never another or more powerful gun, its always more ammunition!". Indeed, most combat flight-sims have a setting you can change to enable infinite ammunition!

This was bought home to me when I compared two combat histories recently. The first is "Flying Sailors at War" by Brian Cull, which covers Blackburn Skua operations over Norway in early 1940. The second is "Whirlwind - Westland's Enigmatic Fighter" By Niall Corduroy; it was Chapter 6 "Operational at Last" that interested me, concerning the Westland Whirlwind's early operations in the South-West of England. Both books have the benefit of the authors having cross-checked the claims of the British pilots against actual Luftwaffe losses. In both periods covered, British pilots were going after similar sorts of targets, Luftwaffe bombers without escorts. So in both cases, the pilots would have been able to concentrate on making a kill, without having to constantly worry they had a Bf109 on their tail. You would expect the Skua, with its "puny" four Browning rifle-calibre machine guns, poor performance and lack of armoured windscreen, to have put up a very poor showing. While the "devastating", longer-range, four cannon armament of the Whirlwind should surely have just blown the Luftwaffe bombers to smithereens, and the extra speed and armoured windscreen of the Whirlwind should have given it the edge in survivability.

Yet that is not what we see in the record. The Skua put up a surprising showing, downing many German bombers, while the Whirlwinds struggled to score and a number were lost to return fire. The one big difference between the Skua and Whirlwind is the duration of fire, the Skua carried 600 rounds for each of its machine guns, giving 31 seconds of firing time; the Whirlwind had 60 rounds per cannon, giving only some 5 seconds of fire. Reading the combat reports the Skuas seemed to take their time, making sure to kill the enemy rear gunner first, before going on to bring down the aircraft. Indeed, that was reportedly the maxim of Lieutenant W.P. Lucy, the only Skua ace. While time and again Luftwaffe bombers escaped when Whirlwinds ran out of ammunition. It may well be that the limited firing time of their cannon made the Whirlwind pilots feel the need to get in close to ensure a kill, which left them open to return fire from the Luftwaffe gunners.

Loading a belt of 600 rounds of .303 ammumition for the wing guns of a Blackburn Skua.

Duration of fire is also ignored in the Luftwaffe "ace" question. How could the German aces run up such phenomenal scores? There are many elements at play here, (I recommend reading Mike Spick's book "Aces of the Reich" for an analysis of the subject) but what is almost never mentioned is the amazingly superior duration of fire advantage enjoyed by Luftwaffe fighter pilots for much of the war, particularly those flying the Bf109. A whole fuselage cross-section of the Bf109E was devoted to ammunition storage with 1,000 rounds for each of its two machine guns, giving a firing time of about 55 seconds, (the action of the propeller interrupter gear slowed down the rate of fire of the MG17 machine guns) three times longer than a Spitfire or Hurricane. That is without taking into account the MG FF cannons which had about 7 seconds duration and could be fired instead of, or together with, the machine guns. The E-1 version of the Bf109 had machine guns in the wings, rather than cannons, with 500 rounds per gun. The late-war Bf109G had 25 seconds of fire from its heavy MG131 machine guns and 16 seconds from its MG151 cannon.

Bf109 E-1 of 2/JG52 shot down in 1940. The lack of cannons protruding from the front of the wings show it to have only machine gun armament. It's possible that up to a third of the Bf109s used in the Battle of Britain lacked cannon armament. Although they only had four machine guns compared to the Spitfire and Hurricane's eight, the Bf109 carried more ammunition. The British had 350 rounds per gun, 2,800 rounds in total, while the Bf109 had a 1,000 rounds for each fuselage gun and 500 rounds for each wing gun, a total of 3,000 rounds.

The question of duration of fire came up during the production of the F4F-4 Wildcat for both the US Navy and the British Royal Navy. The Americans wanted the number of guns reduced from six to four but with increased amounts of ammunition for each gun. This is understandable since in the swirling one-on-one dogfights with Japanese Zeros above the Pacific the first pilot to run out of ammunition would usually be the loser. Meanwhile, the British wanted the Wildcat to retain its six-gun armament, since they wanted to knock out large, long-range, four-engined Focke-Wulf Condors with a single firing pass. Many American F4F-4 pilots would deselect the outer two guns for initial combat, only enabling them once the inboard four guns had run out of ammunition as a way of extending firing time. Later production of the FM-1 and FM-2 versions of the Wildcat by the Eastern Aircraft Company switched to a four-gun armament.

Pat Pattle, arguably the top-scoring Commonwealth ace of the war, scored a lot of his victories in Gloster Gladiators, a type with 600 rounds for each of the fuselage guns, allowing almost twice the duration of fire of the Hurricane and Spitfire. Likewise, the two top-scoring American aces, Richard Bong and Thomas McGuire, flew the P-38 Lightning, the US fighter with the longest duration of fire (500 rounds of .50 calibre ammunition per gun giving 35 seconds duration).

YouTube is full of gun camera footage from WW2 and it is notable how many times pilots "walk" their rounds onto, or through a target on strafing attacks, using prolonged bursts of fire, another advantage of a large ammunition capacity.

Does an expert marksman benefit more from having a larger amount of ammunition or a heavier and more damaging round? Does having a larger ammunition capacity give a pilot confidence to try some "speculative" shooting at longer range? Does a novice pilot benefit from a longer duration of fire to get on target? Does a longer duration of fire enable a pilot to take advantage of those rare "target-rich environments" when they occur?

If you were given the choice, what would you choose; more or heavier guns, or more ammunition?

NOTES

¹ In most books and articles from the 1950s through to the 1990s, Air Marshal Sir Ralph Sorley is usually credited with the adoption of 8 machine guns in the Spitfire and Hurricane, however, the full story is a lot more complicated. I recommend reading chapter 5 "The Quest for Fighter Firepower" in Colin Sinnott's book "The RAF and Aircraft Design 1923-39" (ISBN 0-7146-5158-3). The Role of Frederick Hill, with the help of his 13 year old daughter Hazel, was also crucial <see link>.

² It had originally been planned that both the Hurricane and Spitfire would have housed two of their eight guns in the fuselage. A photograph of the fuselage installation in the prototype Hurricane appeared in a letter by David Lloyd in the Air Corresponence feature in issue 39 of The Aviation Historian magazine.

³ To confirm the Royal Navy continued to use the Lewis through the first year of WW2 see page 106 of Matthew Willis' book "Blackburn Skua and Roc" (ISBN 978-83-89450-44-9).

⁴ This incident happened on 31st October 1940, the gunner was W.S. "Sticks" Gregory (later Wing Commander) flying with Plt Off Rhodes. - Details can be found in Chapter 10 "Battle Day of an RAF Pilot" of "The Battle of Britain - The greatest battle in the history of air warfare" by various authors, this particular chapter by Richard Townshend Bickers. ISBN 1 85613 025 8.

⁵ When first introduced into service, the Japanese Army Ho-103 machine gun (the Japanese often referred to it as a "cannon") was extremely unreliable and would often jam. Worse still, it would also experience explosions in the breech. On installations above the engine of the Japanese Army Ki-43-1 "Hayabusa" (Oscar) fighter, this would disable the engine! The Ki-43-1 had to have a sheet of metal installed to protect the engine from such occurrences (this at a time when the Ki-43-1 carried no armour to protect the pilot!). Although the Ki-43-1c were capable of mounting two Ho-103, most flew with only a single one installed, the place of the other taken by a Type 89 rifle-calibre gun so that the pilot still had at least one weapon when the Ho-103 inevitably jammed. The defects in the Ho-103 seem to have been resolved by the time they were installed in the later Ki-43-2 and Ki-43-3 variants. See the article "Falcons on Every Front - Nakajima's Ki-43-I Hayabusa in Combat" by Mark Huggins in issue 131 (Sept/Oct 2007) of Air Enthusiast Quarterly Magazine.

⁶ For details of the problems with the .50 calibre gun on the Brewster Buffalo see the early chapters of "Buffaloes over Singapore" by Brian Cull, Paul Sortenhaug and Mark Haselden. ISBN - 1-904010 32 6

⁷ See Matt Willis' article "The Many Behind the Few" in the September 2020 edition of Aeroplane Monthly magazine, also his article "The Missing Link?" in issue 40 (July 2022) of The Aviation Historian magazine.

⁸ The St Petersburgh Declaration does not actually specify 37mm (1½ inches) as the minimum calibre for exploding shells but to confirm that at the time this was seen as the minimum calibre by the Air Ministry see chapter 5 (page 117) "the Quest for Fighter Firepower" in Colin Sinnott's book "The RAF and Aircraft Design 1923-39" ISBN 0-7146-5158-3. During WW1, British airman had considered it illegal to use incendiary ammunition against aircraft targets, (reserving it only for attacking balloons) - see chapter 6 of Norman Frank's "Dog Fight - Aerial Tactics Of The Aces Of The First World War", ISBN: 978-1-84832-832-7.

⁹ Number 5 Group of RAF Bomber Command adopted an aggressive policy of their gunners opening fire on German night-fighters as soon as they were sighted, regardless of if the German fighter had itself opened fire. Most other Bomber Command crews did not open fire until it was obvious that the Germans had spotted them, thereby hoping to slip away unseen. Analysis of losses suggests this latter course was a better policy (see the article by Wg Cdr Jefford listed in sources below).

² It had originally been planned that both the Hurricane and Spitfire would have housed two of their eight guns in the fuselage. A photograph of the fuselage installation in the prototype Hurricane appeared in a letter by David Lloyd in the Air Corresponence feature in issue 39 of The Aviation Historian magazine.

³ To confirm the Royal Navy continued to use the Lewis through the first year of WW2 see page 106 of Matthew Willis' book "Blackburn Skua and Roc" (ISBN 978-83-89450-44-9).

⁴ This incident happened on 31st October 1940, the gunner was W.S. "Sticks" Gregory (later Wing Commander) flying with Plt Off Rhodes. - Details can be found in Chapter 10 "Battle Day of an RAF Pilot" of "The Battle of Britain - The greatest battle in the history of air warfare" by various authors, this particular chapter by Richard Townshend Bickers. ISBN 1 85613 025 8.

⁵ When first introduced into service, the Japanese Army Ho-103 machine gun (the Japanese often referred to it as a "cannon") was extremely unreliable and would often jam. Worse still, it would also experience explosions in the breech. On installations above the engine of the Japanese Army Ki-43-1 "Hayabusa" (Oscar) fighter, this would disable the engine! The Ki-43-1 had to have a sheet of metal installed to protect the engine from such occurrences (this at a time when the Ki-43-1 carried no armour to protect the pilot!). Although the Ki-43-1c were capable of mounting two Ho-103, most flew with only a single one installed, the place of the other taken by a Type 89 rifle-calibre gun so that the pilot still had at least one weapon when the Ho-103 inevitably jammed. The defects in the Ho-103 seem to have been resolved by the time they were installed in the later Ki-43-2 and Ki-43-3 variants. See the article "Falcons on Every Front - Nakajima's Ki-43-I Hayabusa in Combat" by Mark Huggins in issue 131 (Sept/Oct 2007) of Air Enthusiast Quarterly Magazine.

⁶ For details of the problems with the .50 calibre gun on the Brewster Buffalo see the early chapters of "Buffaloes over Singapore" by Brian Cull, Paul Sortenhaug and Mark Haselden. ISBN - 1-904010 32 6

⁷ See Matt Willis' article "The Many Behind the Few" in the September 2020 edition of Aeroplane Monthly magazine, also his article "The Missing Link?" in issue 40 (July 2022) of The Aviation Historian magazine.

⁸ The St Petersburgh Declaration does not actually specify 37mm (1½ inches) as the minimum calibre for exploding shells but to confirm that at the time this was seen as the minimum calibre by the Air Ministry see chapter 5 (page 117) "the Quest for Fighter Firepower" in Colin Sinnott's book "The RAF and Aircraft Design 1923-39" ISBN 0-7146-5158-3. During WW1, British airman had considered it illegal to use incendiary ammunition against aircraft targets, (reserving it only for attacking balloons) - see chapter 6 of Norman Frank's "Dog Fight - Aerial Tactics Of The Aces Of The First World War", ISBN: 978-1-84832-832-7.

⁹ Number 5 Group of RAF Bomber Command adopted an aggressive policy of their gunners opening fire on German night-fighters as soon as they were sighted, regardless of if the German fighter had itself opened fire. Most other Bomber Command crews did not open fire until it was obvious that the Germans had spotted them, thereby hoping to slip away unseen. Analysis of losses suggests this latter course was a better policy (see the article by Wg Cdr Jefford listed in sources below).

SOURCES

The books and website of Anthony G Williams and Emmanuel Gustin, at the link below.

"Defensive Gun Armament" an article by Wg Cdr Jeff Jefford in 45th issue of the Journal of the RAF Historical Society.

An archive of the Journal is avalable at the RAF Museum Website- see link below.

Matt Willis' article "The Many Behind the Few" is in the September 2020 edition of Aeroplane Monthly magazine. He covers the same subject in his article "The Missing Link?-0.303 Vs0.5in armament" in issue 40 (July 2022) of The Aviation Historian magazine.

Mark Russell's articles "The Vickers are Coming" in issue 45 (October 2023) of The Aviation Historian magazine, and "Surefire- The Lewis Automatic Machine Gun in British Service" in Issue 47 (April 2024).

"F4F Wildcat in Action" - Number 84 in the Squadron/Signal "In Action" series by Don Linn. ISBN 0-89747-200-4.

"Armament Flight" an article by Wing Commander R.E. Havercroft, recalling his part in armament trials with the "Aircraft Gun Mounting Establishment" at Duxford and then A&AEE at Boscombe Down. Published in the May 1987 edition of Aeroplane Monthly magazine.

"Armament of British Aircraft 1909-1939" by H.F. King, published by Putnam in 1971. ISBN: 0 370 00057 9.

LINKS

Cannons and machine guns - What's the difference?

The Website of Emmanuel Gustin, alongside Anthony G Williams, the foremost writers on the subject of aircraft gun armament.

RAF Museum archive of the Journal of the RAF Historical Society - Issue 45 covers guns.

Vickers machine gun on the "Plane Encyclopaedia" website.

Vickers K machine gun on Wikipedia

Vickers K machine gun video on the Forgotten Weapons Youtube channel.

Browning .303 on Aviation History website.

Browning .303 on Military Factory website

Browning .50 on Aviation History website

Browning .303 Video in the Forgotten Weapons Youtube channel.

Browning .50 on Wikipedia

Hispano 20 mm Cannon on Wikipedia

Page devoted to British .303 incendiary ammunition.

COW gun on Wikipedia

COW gun on Perth Flying boat (YouTube)

Tsetse Mosquito with 57mm Molins gun (YouTube)