Dinger's Aviation Pages

No-allowance shooting

A short description

"No-allowance shooting is simple; give any 19-year-old a machine gun, some tracer ammunition, and put him in the front seat of an FE 2b and he'll discover it for himself." WWI air gunner.

A short description

"No-allowance shooting is simple; give any 19-year-old a machine gun, some tracer ammunition, and put him in the front seat of an FE 2b and he'll discover it for himself." WWI air gunner.

No-allowance shooting, also known as non-deflection shooting or non-deflection sighting is a principle of air combat first discovered and used during World War One. It heavily influenced the specifications drawn up for new fighter aircraft by Britain's Royal Air Force (RAF) in the 1920s and 30s, being largely ignored by the air-arms of other countries. It is therefore ironic that the biggest and most successful use of the principle was made by the German Luftwaffe in the form of the Scräge Musik upward-firing guns used in their night fighters against British bombers in World War Two.

An appreciation of no-allowance shooting is essential to anyone wanting to make sense of the various RAF specifications for new designs of fighter that originated between the two world wars, and yet very little is written about this subject, and what there is often confuses the matter. The term "no-deflection" is sometimes used to denote shooting at an enemy aircraft from directly behind and at very close range, so close that no allowance for bullet drop or deflection need be made; that is not the sense of "no-deflection" this web-page is about.

An appreciation of no-allowance shooting is essential to anyone wanting to make sense of the various RAF specifications for new designs of fighter that originated between the two world wars, and yet very little is written about this subject, and what there is often confuses the matter. The term "no-deflection" is sometimes used to denote shooting at an enemy aircraft from directly behind and at very close range, so close that no allowance for bullet drop or deflection need be made; that is not the sense of "no-deflection" this web-page is about.

Beginnings and principles.

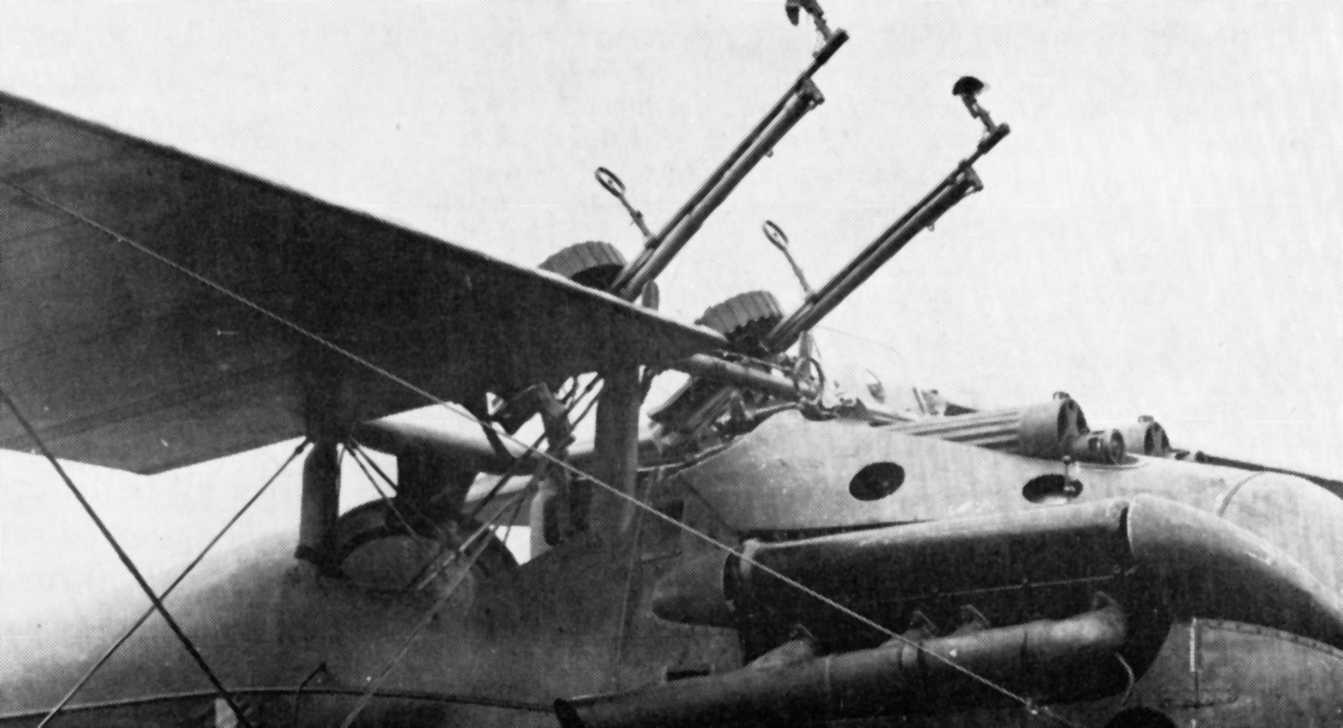

No-allowance shooting was first discovered by aviators in the early stages of World War One. Its early users were the front gunners in pusher biplanes such as the British Fe2b; where the front gun is free to be pointed in any direction that the airframe will allow. The principle was then later used by pilots flying aircraft fitted with a "Foster mount" that allowed a machine gun on the top of the wing of a biplane to be swung down into the cockpit to have its ammunition drum changed. The Foster mount also allowed the machine gun to be fired at any angle from straight ahead to vertically upwards. Aircraft that used the Foster mount included the French Nieuport 17 and the British SE5. The most famous user of no-allowance shooting being the British ace Albert Ball VC who flew both the Nieuport and SE5.

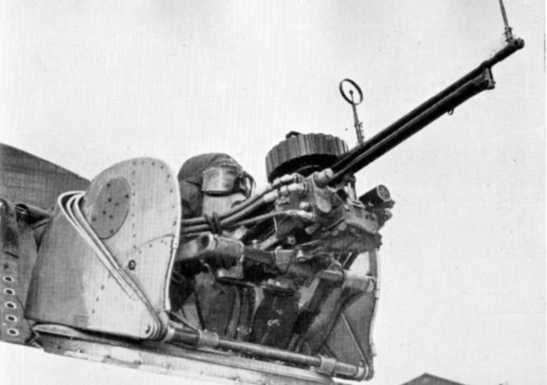

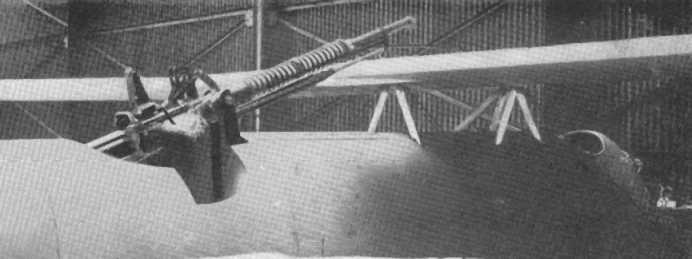

Foster Mount: It allowed the machine gun to be mounted on top of the wing to fire outside the arc of the propeller, yet allowed the gun to be pulled back for the ammunition drum to be changed. But it also allowed the gun to be fired at an angle upwards and take advantage of no-deflection shooting.

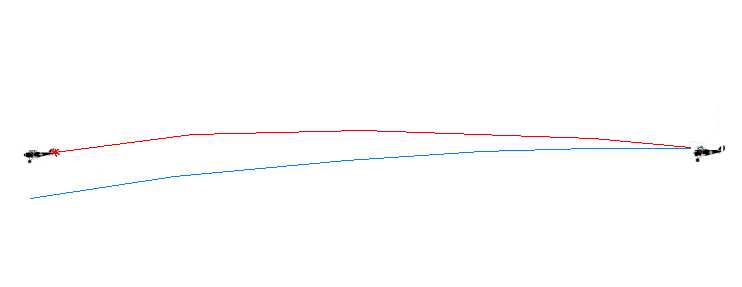

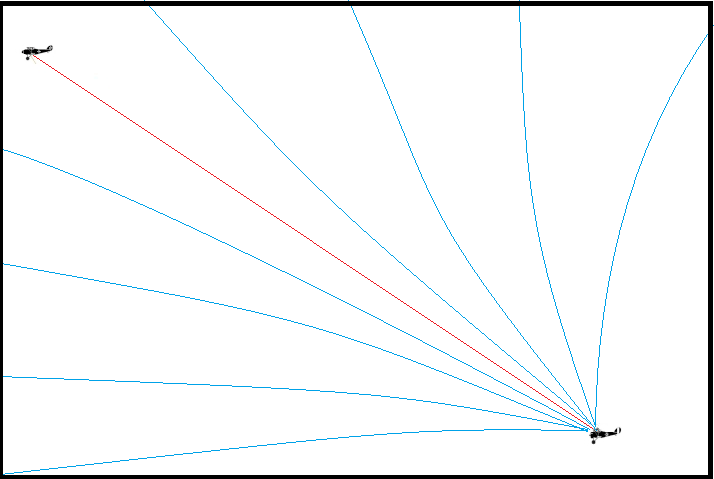

To explain no-allowance shooting imagine you are flying a Nieuport fitted with a Foster mount with the gun pointed straight ahead. Your ammunition drum is loaded with tracer to observe the flight of the bullets. You fire the gun; what do you see? As soon as the bullet leaves the barrel gravity will start to act on the bullet, causing it to start arcing downward. Therefore, to hit a target at some distance ahead you have to allow for this "bullet drop" by "aiming-off" and firing at a point above your target. Now you use the Foster mount to pull the gun back a little so it is angled a few degrees upwards; you fire again. You see the bullets climb, but again after a second or so they start to curve down to earth. The diagram below (obviously not to scale and with the curves exaggerated) shows the situation. The blue line showing the flight of bullets straight ahead and the red when the gun is angled up a few degrees.

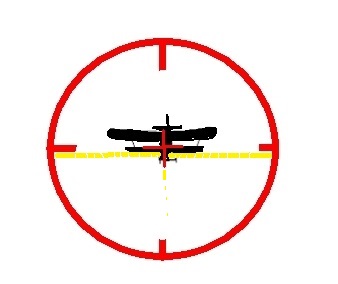

To hit a far-off target straight ahead you need to aim above it to allow for bullet drop. Note that the bullets curve down towards the bottom of the sight.

BULLETS CURVE TOWARDS THE BOTTOM OF THE SIGHT.

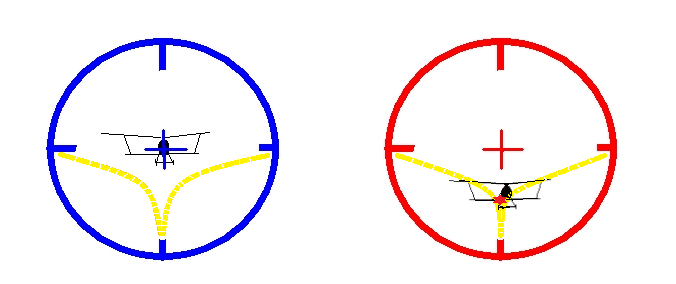

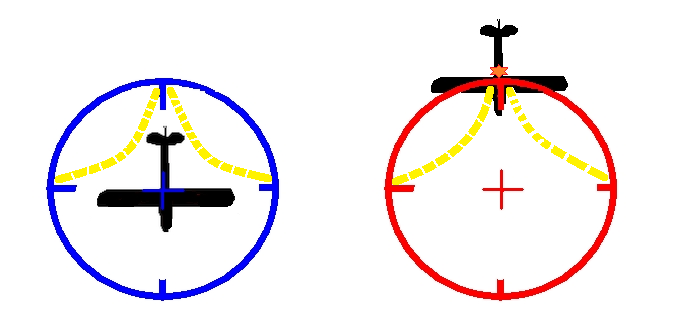

Now you pull the gun all the way back so that it is pointing vertically upwards. You fire again; what do you see? The bullets go up, but because the aircraft is travelling forward at nearly 100mph they are left behind. To you, in the aircraft, the bullet seems to curve backwards. You then push the gun forward so that it is angled forward a few degrees and fire again, again the bullets curve backwards as from your point of view you catch them up and leave them behind. It is important to stress that this is caused by your forward motion. The bullets themselves never actually start to go backwards, it is your aircraft leaving them behind that gives rise to the illusion, however, if you were firing at an enemy you would have to allow for this deflection and "aim-off" to achieve hits.

To hit a target flying directly above you, you have to aim in front of it. Note the bullets curve up towards the top of the sight..

BULLETS CURVE TOWARDS THE TOP OF THE SIGHT

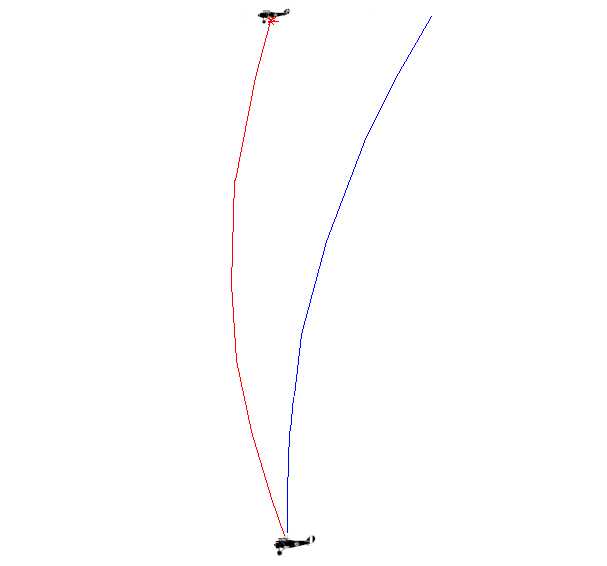

Now, if bullets fired forward curve downwards, towards the bottom of the sight, because of gravity, and bullets fired upwards appear to curve back, towards the top of the sight, because they are caught up with and left behind by the forward motion of the aircraft, what happens when we pull the gun to a mid-way position? At what point will bullets stop curving downwards towards the bottom of the sight and start to curve backwards towards the top of the sight? It is a matter of common sense that there must be a point where one effect is cancelled by the other, a "sweet spot" at which, from the pilot's point of view, the bullet just appears to keep going in the direction it was fired. You've discovered no-allowance shooting! The angle at which you do not need to aim off to allow for deflection.

To hit an aircraft in front, you need to aim above it . To hit an aircraft above, you need to aim in front of it. If an aircraft in front of you was to rise up (or your aircraft drop down) there comes a point where you would have to swap over from aiming above the target to aiming in front of it. At that point you'd be aiming directly at the target and would not have to aim-off or allow for any deflection.

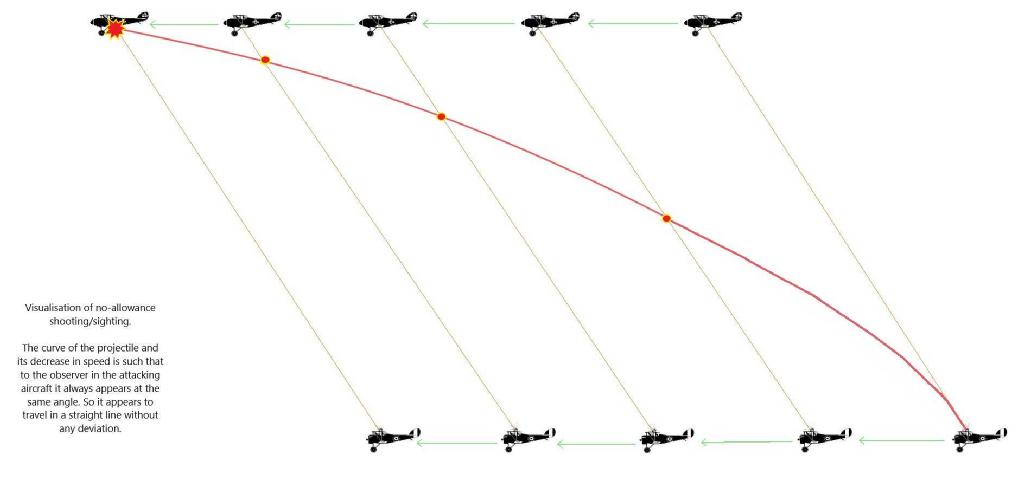

As the stream of bullets change from curving towards the bottom of the sight to curving towards the top of the sight there comes a critical point where they seem to just go straight. They will eventually curve downwards but after only after a prolonged period of seeming to go straight.

The advantages of no-allowance shooting are many. If you can formate under the tail of an enemy aircraft and fly at the same speed, with no "aiming-off" you can virtually guarantee to score hits, and you can open fire at greater range. The position under the tail of the enemy is ideal for approaching without being seen if the target does not have a ventral gun position. The method is perfect for bringing down unescorted bombers flying in formation, with each bomber "locked" into its position within the formation it can do little to avoid an attack by no-deflection sighting, particularly if the attacker can use a longer range cannon to make the attack without getting into range of the bomber's defensive armament. Against night-bombers the no-deflection method is particularly effective, approaching from below the bomber will be silhouetted against whatever light there is remaining in the sky, whereas the attacking fighter will be lost against the "gloom" of the ground. When the bomber starts to take evasive manoeuvres it can be more easily kept in view by an aircraft below and behind, whereas an attacker directly behind can easily lose view of a bomber if it drops below its nose suddenly.

Notice in the above diagram, that although the projectile is travelling in a curved path, to the pilot in the attacking aircraft it always appears at the same angle and thus appears to travel in a straight line to the target.

The angle at which no-allowance shooting works depends on two factors; the speed of the aircraft through the air and the velocity of the bullet. For an aircraft in World War One, the angle is in the order of 45 degrees. The increased speed of aircraft in World War Two meant the angle was reduced to about 20 degrees or even as little as 10 degrees.

Machine guns on a Bristol fighter late in WW1. There were two Lewis guns for the pilot mounted for no-allowance attacks and two Lewis guns for the rear gunner that could also be used for no-allowance fire. A formidable upward-firing armament.

The armament of the Sopwith Dolphin fighter consisted of two Vickers guns firing straight ahead and two Lewis guns mounted for no-allowance attacks.

Some writers have attributed the use of no-allowance shooting to a perception that bullets or shells fired at an angle to the aircraft's airflow would act rather like a wing; generating lift and therefore extending their range. However, the resulting increase in range would be very small indeed (if at all) and has no bearing on the ability of the pilot to fire on a target without having to allow for deflection. In the 1970s I had the opportunity to talk to some old WW1 and inter-war air gunners about no-allowance shooting (or rather, they gave me a lecture on the subject over some beers in a British Legion club). The description they gave me did not fit with the "extra lift" explanation at all; rather they stressed the simplicity of just observing that your tracer went in a straight line when the gun was at a certain angle. One of them said he had first been shown the principal by being driven up and down a grass airfield in a Hucks starter and throwing tennis balls at a target attached to the end of the driving shaft. The same chap said there had been an uproar amongst air gunners when the first Hawker Demon fighter arrived at their squadron; they found that the cut-away gunner's position, meant to protect gunners from the slipstream, did not allow the machine gun to be fired in a no-allowance shooting mode (the earlier "Hart fighter" was a straight conversion of the Hawker Hart bomber and did not have the issue). It was complaints about this that led to the adoption of the "lobsterback" Fraser-Nash turret that still protected the gunner from the slipstream, while still allowing no-allowance shooting over the top of the upper wing.

The Fraser-Nash "lobsterback" turret fitted to later Hawker Demon two-seat fighters. It protected the gunner from the slipstream (when rotated to point backwards) while still allowing him to fire over the top of the upper wing.

The Specifications and Designs.

Between the wars, there was a series of specifications for new fighters released by the RAF that sought to maximise the potential for no-allowance shooting. In 1924 specification F4/24 called for a twin-engined design mounting a pair of the new automatic 37mm (1½ inches) Coventry Ordnance Works guns (known as "COW guns") firing forward at no-allowance angles. This led to two designs, the Type95 "Bagshot" ¹ from Bristol and the Westland "Westbury" but no production orders were forthcoming. The same year, specification 27/24 was issued which resulted in the twin-engined Boulton Paul Bittern fighter prototype with machine guns in revolving barbettes in the nose.

The rear COW gun position of the Westland Westbury showing the gun was positioned to fire forward over the top of the upper wing. Another COW gun was located in the bow of the aircraft.

Then in 1927, specification 29/27 gave rise to two prototypes, one from Vickers, the other from Westlands, each mounting a single "COW Gun" fitted to fire upwards at a no-allowance angle. This was part of the RAFs desire to acquire "interceptor" fighters (read about that in this article "The First Interceptor").

The Vickers Cow gun fighter: It looks very anachronistic for an aircraft that first flew in 1931. The interceptor-style specification for which it was built stressed the ability to climb to altitude very quickly, something the large wing area of its biplane layout was ideal for. In fact, the Vickers design was as fast as the monoplane COW fighter produced by Westland while possessing a much superior rate of climb.

The Westland COW gun fighter was based on their "interceptor" fighter to F20/27 but with the big COW gun fitted adjacent to the pilot, its barrel enclosed in a streamlined fairing for part of its length. The monoplane configuration looks comparatively modern, but it had bracing wires above and below the wing and the performance was lacklustre.

Specification F5/33 called for a two-seater fighter with the main armament in a turret in the nose, this did not lead to any prototypes but it did push forward turret development.

One of the designs tendered for F5/33 was the Boulton Paul P76. It featured the same turret as used in the Boulton Paul Overstrand bomber in the nose with a bank of machine guns in the fuselage arranged to fire upwards at 45 degrees. Boulton Paul put forward two variants; the P76A powered by two 350hp Napier Rapier inline air-cooled engines (expected top speed 217 mph / 349 kph) and the larger P76B with two 700hp Bristol Pegasus Radial engines (expected top speed 247 mph / 397 kph). This illustration shows them tackling Focke Wulf FW42 bombers, a German "might-have-been" canard design of the same vintage.

In 1934, A&AEE at Martlesham Heath ran a series of tests with a pair of Vickers machine guns mounted in a Bristol Bulldog fighter (serial number J9567) to fire upwards at an angle of 60 degrees. Flying 1,000 feet (300 metres) underneath a target drogue an astonishing 90 percent of rounds fired hit the target.

The upward-pointing machine guns and sight fitted to a Bristol Bulldog fighter. An amazing 90% score was achieved on towed targets at 1,000 feet (300 metres).

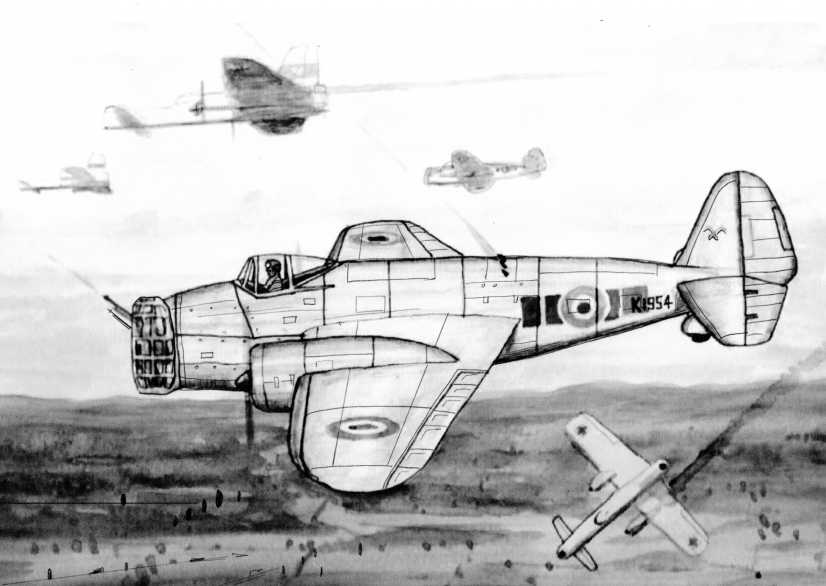

This led eventually to Spec 9/35 and the Boulton Paul Defiant turret fighter (its slower naval counterpart the Blackburn Roc was covered by 15/37). There can be no doubt that no-allowance shooting was inherent in the design of the Defiant; for example, the gun turret of the Defiant could be locked into position and then fired by the Defiant pilot.²

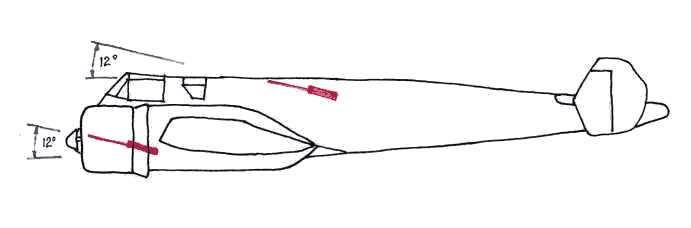

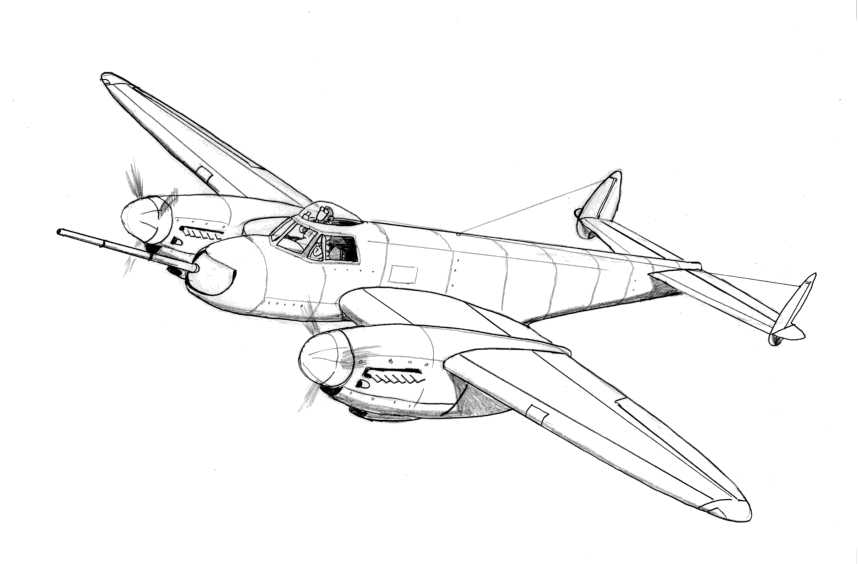

Specification F9/37 which led to the Gloster G39 prototype, which was designed to have 3 cannon in the fuselage behind the pilot firing upward at a no-allowance angle (12 degrees), and another two in the nose, also firing up at at the same angle.

View of the first prototype Gloster G39 F9/37 fighter showing the bulged rear fuselage to accommodate the upward-firing armament of three 20mm cannons. There would also have been two 20mm cannon mounted in the nose, but also at an angle to fire upwards. This initial prototype was powered by a pair of air-cooled Bristol Taurus sleeve-valve engines of 1,050 horsepower and had a remarkable performance; being as fast as a Spitfire Mk I. The first prototype was never fitted with any armament. The second prototype was powered by two of the lower-powered liquid-cooled Rolls-Royce Peregrine engines with chin radiators and had a lower performance, but it was fitted with full armament. Photographs in Tony Buttler's book "British Experimental Combat Aircraft of World War II" show the armament fitted. By the time the prototypes flew the rival Bristol Beaufighter was starting into production and to proceed with the G39 would have taken resources away from other vital projects. A follow-up design with two Merlin engines called "The Reaper" was also cancelled, the design staff at Gloster concentrating on what was to become the Meteor twin-jet fighter and its single-engined stable-mate the "Ace".

Side view of the Gloster F9/37 showing the alignment of the cannons. Two were in the nose and three amidship.

The Gloster G39 F9/37 painted as if it had gone into production.

Gloster G39 F9/37 in night-fighter colours (Planet scale model).

Another expression of confidence in the no-allowance shooting philosophy was Air Ministry specification F11/37 which specified a cannon armament in a power-operated turret. Of the three companies who tendered to this specification, two (Armstrong Whitworth and Bristol) had turrets that could only traverse through the forward hemisphere and hence were plainly designed with no-allowance attacks in mind.

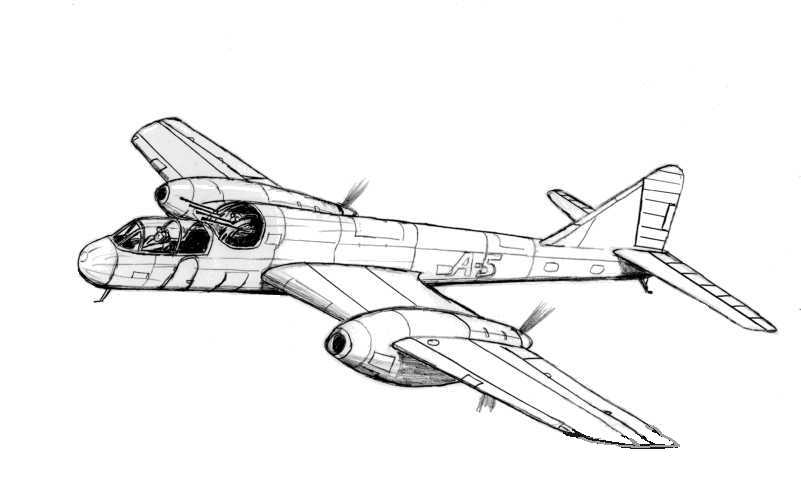

The Armstrong Whitworth design for Air Ministry specification F11/37 was powered by two Merlin engines in a "pusher" configuration. Its armament of four 20mm cannons was accommodated in a turret that could only be rotated around the forward hemisphere. The cannons could not be depressed far enough to fire horizontally, clearly showing it was intended to be used in no-allowance attacks.

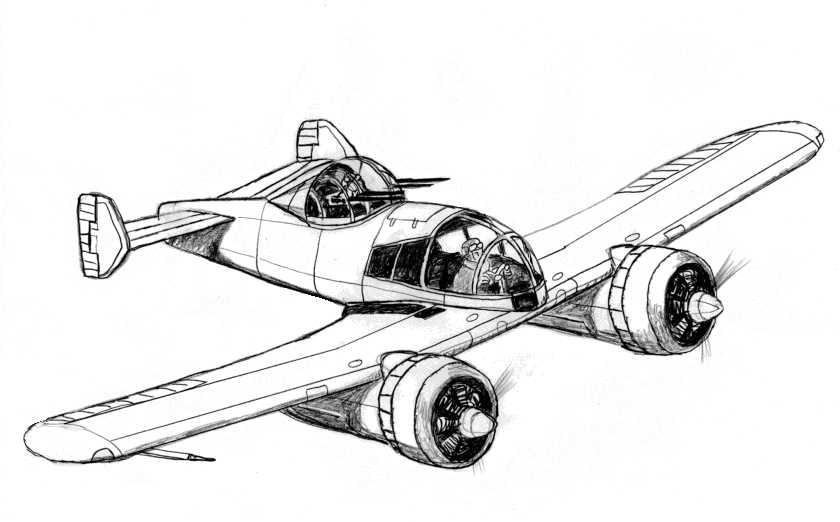

The Bristol tender to specification F11/37 came in two versions. The first with a pair of Hercules engines and a second "scaled up" version with two of the bigger Centaurus engines. Both featured a turret with four 20mm cannon that could only be operated in the forward hemisphere. The design was similar in layout to the single-seat Grumman XF5F Skyrocket fighter, although much larger.

The Boulton Paul P92, its turret was planned to take four 20mm cannon and four machine guns. There were also planned to be another two cannon firing forward through hollow propeller hubs. Read about the P92 at <this link>).

F22/39 was an Air Ministry Specification written around the Type 414 twin-engined fighter design being developed by Vickers. This clearly has no-allowance sighting at the heart of the thinking behind the design and can be seen as the rational successor to the Vickers COW gun fighter of the previous decade. It envisioned a streamlined monoplane two-seater fighter (looking a little like a DH Mosquito but with a twin-rudder tail) mounting a large 40 mm cannon in the nose in a remotely controlled turret which could be elevated for no-allowance shooting.

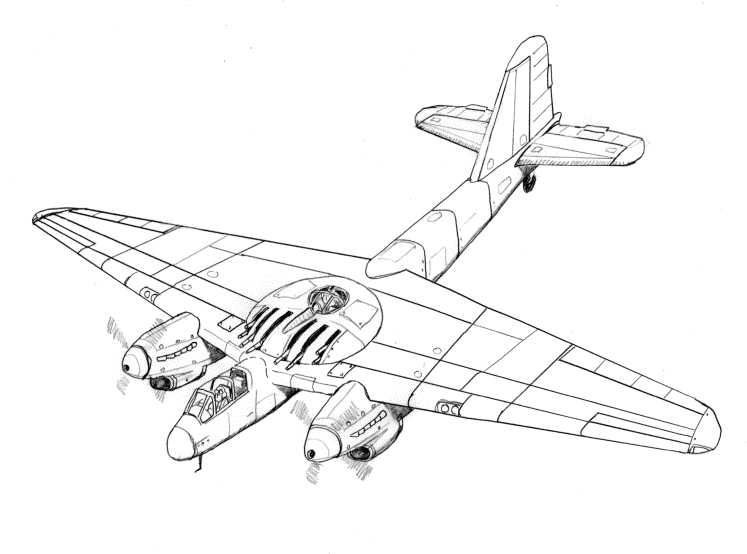

The Vickers Type 414 design tendered to specification F6/39. A successor to the Vickers "COW" fighter of a decade before. Powered by two RR Griffon engines and mounting its 40mm gun in the nose. The gunner sat beside the pilot with his head in a perspex blister. The gun installation and sighting installation were tested successfully in place of the front turret of a Wellington bomber.

Amazingly, Colin Sinnott in his masterly book "The RAF and Aircraft Design 1923-1939" shows that before WWII the RAF was calling for ways for the wing-mounted armament of Hurricanes and Spitfires to be somehow elevated to fire at no-allowance angles! Indeed this requirement was taken forward to the specification that led to the Hawker Typhoon.

Something that you have to keep in mind when reviewing British interest in no allowance shooting is that it was seen as a way to counter enemy bombers attacking the UK. It was not anticipated that those bombers might be escorted by nimble single-engined fighters. It was the German territorial gains of over-running France, Belgium and Holland that put Britain within range of German Bf109 escort fighters. The presence of these escorts during the Battle of Britain quickly dampened enthusiasm for no-allowance shooting for daylight fighters. However, for night-fighters no-allowance shooting was still seen as desirable and this led to specification F18/40 calling for a fighter with forward-facing cannon armament with a turret with machine guns capable of being used against night-bombers from below. The Miles Aircraft Company was amongst those that produced design studies for F18/40. Their submission, the M.22A, could be configured in various ways. Diagrams from the company archive show layouts with no less than 6 upward-firing cannons.

The Boulton Paul P97B was one of the tenders for F18/40. It was a big twin-boom design powered by two Napier Sabre engines. Armament was a type-A four-gun turret as used on the Defiant along with two forward-firing 20mm cannons. Quite similar in layout to the US Northrop P-61 Black Widow night-fighter.

During the night-blitz of the winter of 1940-41 the Defiant turret-fighter did achieve some successes, many in a no-allowance shooting scenario but the new Bristol Beaufighter, with its on-board interception radar, had a better rate of interceptions. Although there were plans to fit Beaufighters with turrets, and prototypes were flown, these plans were dropped and production was concentrated on the version with only forward-firing armament. Over the course of that winter of 1940 - 41 British interest in developing the no-allowance shooting method faded and disappeared, although a single Douglas Havoc (serial number BD126) was fitted with six upward firing machine guns and tested during 1941. The Defiant continued in the night-fighter role until the spring of 1942. It was noted that although radar-equipped Beaufighters were far more likely to make an interception, once an enemy bomber was sighted a Defiant was more likely to go on to shoot it down, even though it did not have the heavy cannon armament of the Beaufighter. This was because the Defiant, approaching from below, was better able to keep the enemy bomber in view once it started taking evasive action. ³

It was in Germany instead that upward shooting was developed to its full combat potential as a weapon of the Luftwaffe night-fighter force. Here it does not seem to have been the result of any official development, rather it was a series of one-off trials by individual pilots and armament technicians that led to its adoption. This was aided by the availability of large stocks of surplus MG FF 20mm cannon that had been replaced by higher velocity MG151 cannon. The compact, low velocity MG FF proved the ideal weapon for fitting into upward firing positions on the various German night fighters.

In the 1950s, the use of upward-firing weapons was once again briefly considered for British fighters. The Fireflash, Firestreak and Red Top guided missile projects had fallen behind schedule and the Royal Aircraft Establishment (RAE) proposed mounting a battery of upward-firing recoilless guns (similar to the British Army's WOMBAT) in a jet fighter. An alternative design mounted a pair of upward-firing 30 mm Aden cannons. The aim was to approach the attacking bomber from the rear and 200 feet (60 metres) below to unleash the recoilless guns in a salvo (or fire the cannon). Infra-red sights were to be provided for use at night or in bad weather. By using upward-firing weapons it was hoped to avoid the fighter having to slow down or turn to avoid collision with the target, thus maintaining speed. The RAE design was sent out to British manufacturers designing the next generation of jet interceptors as an example of the type of aircraft they were considering.

It was in Germany instead that upward shooting was developed to its full combat potential as a weapon of the Luftwaffe night-fighter force. Here it does not seem to have been the result of any official development, rather it was a series of one-off trials by individual pilots and armament technicians that led to its adoption. This was aided by the availability of large stocks of surplus MG FF 20mm cannon that had been replaced by higher velocity MG151 cannon. The compact, low velocity MG FF proved the ideal weapon for fitting into upward firing positions on the various German night fighters.

In the 1950s, the use of upward-firing weapons was once again briefly considered for British fighters. The Fireflash, Firestreak and Red Top guided missile projects had fallen behind schedule and the Royal Aircraft Establishment (RAE) proposed mounting a battery of upward-firing recoilless guns (similar to the British Army's WOMBAT) in a jet fighter. An alternative design mounted a pair of upward-firing 30 mm Aden cannons. The aim was to approach the attacking bomber from the rear and 200 feet (60 metres) below to unleash the recoilless guns in a salvo (or fire the cannon). Infra-red sights were to be provided for use at night or in bad weather. By using upward-firing weapons it was hoped to avoid the fighter having to slow down or turn to avoid collision with the target, thus maintaining speed. The RAE design was sent out to British manufacturers designing the next generation of jet interceptors as an example of the type of aircraft they were considering.

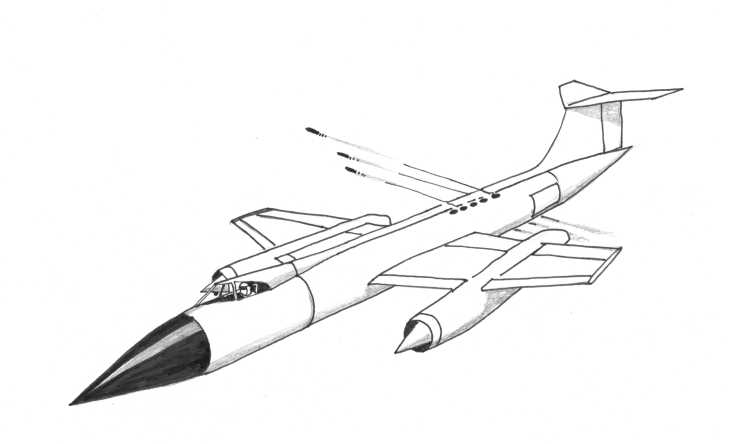

The Royal Aircraft Establishment's idea for a fast interceptor featured a battery of 16 to 25 upward-firing recoilless weapons in the rear of the fuselage. An alternative was to have upward-firing 30 mm Aden cannons. These weapons systems were seen as an alternative or supplement to guided missiles.

Notes

¹ The Bristol Bagshot prototype suffered from alarming flexing of the wings which caused the Bristol design staff to go away and design a very strong wing. This found use in the Bristol Bombay transport/bomber which had a small production run and proved a valuable asset in World War Two. The wing was then developed and used in the post-war Bristol Freighter / Superfreighter.

² I've had some people express doubts about the fact that the Defiant's guns could be fired by the pilot - Can I just point out this quote from the Defiant Pilot's Notes (AP1592B) - Section 1 Paragraph 2: "The control column is operated in the normal way and is mounted on the forward edge of the pilot's seat. The spade-grip is of standard type and incorporating a brake operating lever (47), and a gun-firing push-button (48) for use when the gun-firing control is taken over by the pilot.". The numbers 47 + 48 refer to numbers on the associated diagram of the pilot's cockpit. The turret had a switch to transfer control of firing the guns to the pilot. This link <click here> takes you to an online copy of the Defiant Pilots notes on the WW2 aircraft .net forum (you'll have to register to view it). If you look at this RAF training film on youtube at the link here <click here> you can see the three-position switch clearly marked "Pilot- Off - Gunner".

³ Early in 1942 some Defiants were fitted with radar, but it was not a success. The radar set had to be operated by the pilot which meant he could not concentrate on flying the aircraft, and looking at the radar screen destroyed his night vision. The only radar-equipped Defiant victory was the shooting down of a Heinkel He 111 on 17th April 1942. Unfortunately, many books and articles written in the 1960s and 70s imply that the Defiant was only a successful night-fighter after it had been fitted with radar; this is simply not the case.

Sources

The idea that Bullets and shells fired at an angle generate lift which increases range and that this was the primary advantage of no-allowance shooting is expressed in this archived webpage on the "wayback" machine <see link>.

For details of the many remarkable designs covered in F9/37, F11/37, F22/39 and F18/40 can I recommend "British Secret Projects: Fighters & Bombers 1935-1950" by Tony Buttler ISBN 1 85780 179 2 It was published by Midland Counties Publishing (an imprint of Ian Allan Publishing).

"The British Aircraft Specifications File" by KJ Meekcoms and EB Morgan ISBN 0 85130 220 3, published by Air Britain also covers these designs but in much less detail and without any illustrations or diagrams.

Details of Boulton Paul designs mentioned in this article can be found in "Boulton Paul 1917-1961 - Aircraft, Projects and Studies" by Les Whitehouse, published in 2021 by Crecy. ISBN: 9781910809488.

Details of the Boulton Paul Defiant can be found in "The Turret Fighters" by Alec Brew, published by the Crowood Press. ISBN 1 86126 497 6.

Details of how the RAF planed to use the Boulton Paul Defiant can be found in the article; "The Defiant's Rationale" by Dr Alfred Price in the October 2008 edition of "Aeroplane" magazine. It is also worth reading for its outline of a 1940 document from A&AEE that justified the turret-fighter concept.

Details of the trials of upward firing machine guns in a Bristol Bulldog, can be found in "British Flight Testing - Martlesham Heath 1920-1939": By Tim Mason, first published by Putnam in 1993. ISBN 0 85177857 7.

Diagrams of the RAE jet designs with upward-firing recoiless guns and Aden cannon can be found in "RAF Secret Jets of Cold War Britain" by Dan Sharp, Published by Morton Media in 2017. ISBN: 978-1-911276-47-0.

The diagrams of the upward-firing cannon layouts for the Miles M.22A fighter can be found on page 158 and 159 of "Miles Aircraft - The Wartime Years", by Peter Amos. Published by Air Britain. ISBN 978 0 85130 430 4.

Pictures of the upward firing machine guns on Douglas Boston DB126 can be found in "The Secret Years - Flight Testing at Boscombe Down 1939-1945" by Tim Mason, published in 1998 by Hikoki. ISBN: 0951899 9 5.

Links

Cannon or machine gun: What's the difference?

Westland COW gun fighter on Aviastar website

Vickers COW gun fighter on Wikipaedia

Notes

¹ The Bristol Bagshot prototype suffered from alarming flexing of the wings which caused the Bristol design staff to go away and design a very strong wing. This found use in the Bristol Bombay transport/bomber which had a small production run and proved a valuable asset in World War Two. The wing was then developed and used in the post-war Bristol Freighter / Superfreighter.

² I've had some people express doubts about the fact that the Defiant's guns could be fired by the pilot - Can I just point out this quote from the Defiant Pilot's Notes (AP1592B) - Section 1 Paragraph 2: "The control column is operated in the normal way and is mounted on the forward edge of the pilot's seat. The spade-grip is of standard type and incorporating a brake operating lever (47), and a gun-firing push-button (48) for use when the gun-firing control is taken over by the pilot.". The numbers 47 + 48 refer to numbers on the associated diagram of the pilot's cockpit. The turret had a switch to transfer control of firing the guns to the pilot. This link <click here> takes you to an online copy of the Defiant Pilots notes on the WW2 aircraft .net forum (you'll have to register to view it). If you look at this RAF training film on youtube at the link here <click here> you can see the three-position switch clearly marked "Pilot- Off - Gunner".

³ Early in 1942 some Defiants were fitted with radar, but it was not a success. The radar set had to be operated by the pilot which meant he could not concentrate on flying the aircraft, and looking at the radar screen destroyed his night vision. The only radar-equipped Defiant victory was the shooting down of a Heinkel He 111 on 17th April 1942. Unfortunately, many books and articles written in the 1960s and 70s imply that the Defiant was only a successful night-fighter after it had been fitted with radar; this is simply not the case.

Sources

The idea that Bullets and shells fired at an angle generate lift which increases range and that this was the primary advantage of no-allowance shooting is expressed in this archived webpage on the "wayback" machine <see link>.

For details of the many remarkable designs covered in F9/37, F11/37, F22/39 and F18/40 can I recommend "British Secret Projects: Fighters & Bombers 1935-1950" by Tony Buttler ISBN 1 85780 179 2 It was published by Midland Counties Publishing (an imprint of Ian Allan Publishing).

"The British Aircraft Specifications File" by KJ Meekcoms and EB Morgan ISBN 0 85130 220 3, published by Air Britain also covers these designs but in much less detail and without any illustrations or diagrams.

Details of Boulton Paul designs mentioned in this article can be found in "Boulton Paul 1917-1961 - Aircraft, Projects and Studies" by Les Whitehouse, published in 2021 by Crecy. ISBN: 9781910809488.

Details of the Boulton Paul Defiant can be found in "The Turret Fighters" by Alec Brew, published by the Crowood Press. ISBN 1 86126 497 6.

Details of how the RAF planed to use the Boulton Paul Defiant can be found in the article; "The Defiant's Rationale" by Dr Alfred Price in the October 2008 edition of "Aeroplane" magazine. It is also worth reading for its outline of a 1940 document from A&AEE that justified the turret-fighter concept.

Details of the trials of upward firing machine guns in a Bristol Bulldog, can be found in "British Flight Testing - Martlesham Heath 1920-1939": By Tim Mason, first published by Putnam in 1993. ISBN 0 85177857 7.

Diagrams of the RAE jet designs with upward-firing recoiless guns and Aden cannon can be found in "RAF Secret Jets of Cold War Britain" by Dan Sharp, Published by Morton Media in 2017. ISBN: 978-1-911276-47-0.

The diagrams of the upward-firing cannon layouts for the Miles M.22A fighter can be found on page 158 and 159 of "Miles Aircraft - The Wartime Years", by Peter Amos. Published by Air Britain. ISBN 978 0 85130 430 4.

Pictures of the upward firing machine guns on Douglas Boston DB126 can be found in "The Secret Years - Flight Testing at Boscombe Down 1939-1945" by Tim Mason, published in 1998 by Hikoki. ISBN: 0951899 9 5.

Links

Cannon or machine gun: What's the difference?

Westland COW gun fighter on Aviastar website

Vickers COW gun fighter on Wikipaedia