Dinger's Aviation Pages

The Vickers Wellesley

The forgotten British aircraft responsible for some of the most successful bombing raids of WWII.

Revised in January 2024 with extra information.

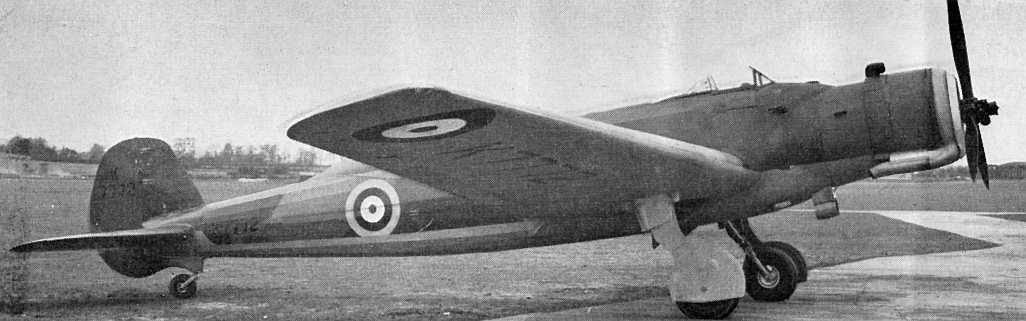

With its huge, high-aspect-ratio wing, geodetic structure, twin canopies and underwing panniers for bombs the Vickers Wellesley had a unique look. This is the prototype K7556 with bomb panniers under the wings. These were deemed to be top-secret and the copies of this photo first released to the press had them airbrushed out. Notice the rear canopy has been rotated forward to form a windshield.

Read most histories of World War Two and chances are you will find no mention of the Vickers Wellesley bomber, and if you do, it may well be dismissed as obsolete and of little importance. Nothing could be further from the truth. Although only available in limited numbers the Wellesley saw extensive combat (albeit only for a limited period) and undertook some of the most important bombing raids of the war, ones that could be said to have had strategic ramifications for the whole conflict. One Wellesley even contributed to the breaking of the German Kriegsmarine's M4 Enigma "Triton" cipher system, having a dramatic effect on the war.

Origins - Type 246

Following the crash of the R101 airship in 1930, the British government stopped all support for rigid airship construction. This freed up Vickers designer Barnes Wallis from his work on the Vickers airship projects. Wallis was keen to employ his thoughts on "geodetic" construction methods. The seeds of which had developed during his work on the R100 airship. Geodetic construction promised to have many advantages, including great strength and less weight, and to cut production costs by being able to be assembled by largely unskilled workers. It had a couple of disadvantages, one was that it needed a great investment in tooling and so required a bigger production run to recoup the investment, and secondly, it was not suitable for small aircraft, to get a benefit from the construction method aircraft had to be of quite large proportions. Wallis first tried out elements of geodetic structure on Vicker's design for a torpedo bomber, the M1/30 (type 207), the prototype of which, unfortunately, was to crash during testing in 1933 (but not because of any failure of the geodetic structure).

Vickers must have been keen to explore this new method of aircraft construction. They were just then bringing to production the first of their "Viastra" series of airliners based on construction methods licenced from the French engineer Michel Wibault. But it must have already been evident that Wibault's methods were a technological dead-end and they must have seen geodetic construction as a way into larger airliner and bomber designs. So they gave Barnes Wallis the go-ahead to design a complete monoplane aircraft based on his new techniques and allocated it the type number 246. It was to be completely financed by Vickers, what was then called a "private venture" (PV). This project was to go on to produce the Wellesley bomber.

The side-show, the Type 253

The traditional (but wrong) way of describing the origins of the Wellesley design is to say it sprang from Air Ministry specification G4/31 issued in 1931 calling for a "General Purpose" aircraft to replace the Westland Wapiti and Fairey Gordon. The aircraft was to be able to do policing actions in the Empire and respond to threats from other colonial powers and carry out coastal patrols. As such it had to function as both a bomber and torpedo-carrying aircraft and be able to defend itself from fighter attack. While a crew capacity of only two was specified the capacity to do casualty evacuation was also desired so it had to include space for a casualty stretcher to be carried. Specification G4/31 promised to be very lucrative to any manufacturer who secured an order, so no less than 10 companies tendered, some with multiple designs.¹

The biplane Vickers Type 253 G4/31, it employed a geodetic design on the rear fuselage. Vickers used government funding for the Type 253 to indirectly finance the development of their Type 246.

But to say the Wellesley was designed in response to G4/31 ignores the fact that the monoplane design that was to become the Wellesley had a much earlier type number (the 246) than the aircraft Vickers ended up tendering for the role (the Type 253). What actually happened was that Vickers jumped at the chance to try out geodetic construction on the fuselage of the type 253 and hence, indirectly, get the government to pay for part of their development of the type 246 "Private Venture". By making the fuselage of both designs essentially the same the cost of developing the 246 must have been cut dramatically. The Air Ministry were not stupid, they were probably just as keen to see what this new geodetic construction was capable of, getting two prototypes for the price of one.

What most histories of the Wellesley miss out is that the formative Vickers Type 246 was first tendered for a different specification altogether, P27/32 in 1932. This specification was to lead to the Fairey Battle bomber. Vicker's tender was by far the most expensive of the seven tenders received by the Air Ministry and it had by far the most protracted lead-time to first delivery of a prototype (a cost of £16,000 with a lead-time of 20 months compared to £10,500 and a lead-time of 12 months for the Fairey Battle). This underscores that it was going to be expensive and time-consuming to tool up for the geodetic airframe.²

Returning for a moment to the "side-show" G4/31 specification. No less than 9 prototypes from different companies were evaluated by the RAF and it was not until May 1935 that they came to any conclusions. It was not the Vickers Type 253 that won the flying evaluation, but the Westland PV7 high-wing braced monoplane, with the Vickers biplane coming a close second, this was even though the prototype PV7 was destroyed in a crash during testing. However, the Air Ministry then reevaluated both designs and decided that the Vickers aircraft was the most effective, ordering a production batch of 150 aircraft. Meanwhile, this 5-year gap had allowed Vickers and Barnes Wallis to refine the Type 246 design, applying geodetic construction to a monoplane wing, together with retracting undercarriage and flaps, to build their type 246 prototype.

The Westland PV7, winner of the fly-off trials for G4/31, it was rejected in favour of the Vickers Type 253. The lessons learnt by Westland helped then develop the Lysander.

Having already ordered the Type 253 biplane, the Air Ministry was faced with a problem when along came Vickers with their new geodetic Type 246 monoplane and demonstrated its amazing performance. Of course, between 1930 and 1935 world affairs had changed considerably. Colonial policing was no longer the top priority, rather it was the threat of German rearmament and a full-blown European war that was concentrating minds. So the Air Ministry seized on this new wonder monoplane and wrote a new specification around it (22/35). Vickers did not have the factory capacity to produce both the Type 253 and the Type 246, so they were happy to have the order for 150 examples of the type 253 biplane cancelled, to be replaced by an order for 96 of the new monoplanes, confident that more orders for it would follow.

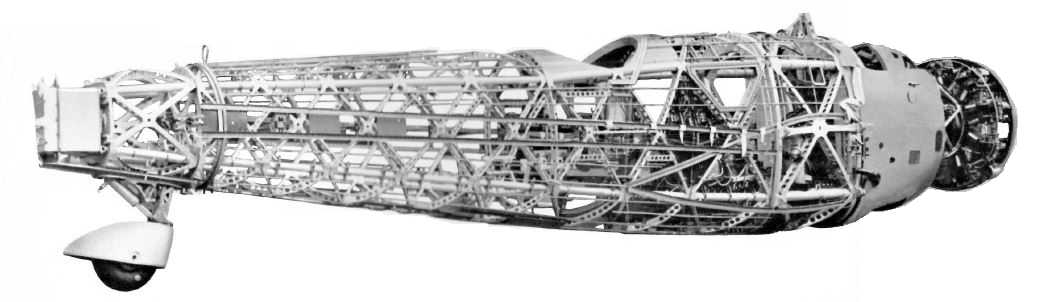

The geodetic structure of the Wellesley fuselage.

It must be stressed here that the new monoplane was not ordered to the earlier G4/31 specification for a general-purpose aeroplane. That earlier specification was abandoned and the new specification was based on Air Ministry Operational Requirement OR24 for a medium bomber.³ The unique requirements of specification G4/31 were never addressed again, the world situation that prompted them back in 1931 having changed forever. However, it is pertinent to point out the aircraft that had actually won the handling trials for G4/31, the high-wing braced monoplane with fixed undercarriage from Westland (the PV7), led indirectly to the high-wing braced monoplane with fixed undercarriage Westland Lysander that would have been ideal for policing actions in the Empire if the political conditions of 1931 had persisted. As it was, biplanes like the Vickers Vincent and Hawker Harts and Hinds, released by the rapid re-equipment of the RAF, were able to plug the gap for colonial policing aircraft.

Refinements- The Type 281 and onto the Type 287

The Type 246 prototype as originally built; with open cockpit and gunners position.

The Type 246 prototype as originally built; with open cockpit and gunners position.

The prototype Vickers type 246 monoplane had an open cockpit for the pilot and an open gunners position. To conform to the new requirement for a medium bomber Vickers extensively changed it. The pilot and gunner positions were given their own, separate canopies and windows were added to the cabin between them suitable for a third crew-member (although it seems no proper seat was provided in that position). The sliding "bubble" pilots canopy was very advanced for its time, and its development by Vickers must have greatly helped the development of the sliding canopy for the Spitfire by Supermarine, (owned by Vickers). The geodetic "basket weave" structure of the aircraft was unsuitable for the addition of a bomb-bay. Instead, bombs were carried in streamlined "panniers", one under each wing (the bomb-bay of the later geodetic Wellington two-engined bomber was external to the geodetic structure, being essentially a "pannier" faired into the bottom of the airframe). It also received an uprated Bristol Pegasus X engine giving considerably more power (980 hp) than the original Pegasus IIIM (only 690 hp). The prototype was given the serial number K7556 and served as the trials aircraft for the production aircraft (there is a photo of it at the top of this page). Vickers changed the type number of the aircraft to type 281 while the Air Ministry allocated the name "Wellesley". It should be noted that the official description of the Wellesley in AP1524A states "The Wellesley I aeroplane is a two-seater monoplane fitted with a Pegasus XX engine. It is intended for day-and-night bombing but may be adapted for general purpose duties".

Early production Wellesley K7718. Notice the rounded rudder and tailwheel enclosed in a streamlined "spat" .

The Wellesley production aircraft were allocated yet another type number (Vickers Type 287). These aircraft incorporated many changes and improvements over the prototype, this included a new fully supercharged version of the Pegasus engine (the Pegasus XX). On the first 39 production Wellesleys (K7713-K7752) a single Vickers .303 machine gun was mounted in the starboard wing with 650 rounds of ammunition. On subsequent aircraft this was replaced by a Browning .303 machine-gun (the Wellesley was one of the first RAF aircraft to mount this new weapon). The gunner had either a .303 Lewis or Vickers "K" gun on a retractable mount along with 8 magazines. His canopy could be rotated forward to protect him from the slipstream. Each bomb pannier could hold either two 250 lb (113 Kg) or two 500 lb (226 Kg) bombs. A smaller bomb-rack was incorporated in the rear of each pannier, each able to hold four small bombs, flares or practice bombs. The aircraft manual stipulated that, when loaded up with 250 or 500 Ib bombs, only the small bomb-rack on the port pannier should be used. An inflatable dinghy could be carried in a compartment in the port wing; its primitive method of activation was via a pull-cable taped along the top of the wing and fuselage to a handle next to the rear gunner's canopy.

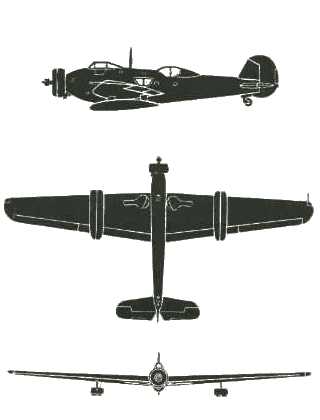

Vickers Wellesley

The Wellesley was equipped with the standard RAF bomber wireless sets of the time, consisting of a type R1082 receiver and a type T1083 transmitter. This incorporated an intercom facility for the crew, with three sockets that crew members could plug their headsets into, one for the pilot, another next to the radio equipment to the rear of the gunner's position and the third in the bomb aimer's position. There was a Morse key to the rear of the gunner's position. There was a trailing wire aerial that could be let out from a reel down a tube under the fuselage to extend the range of the radio.

Crewing the Wellesley

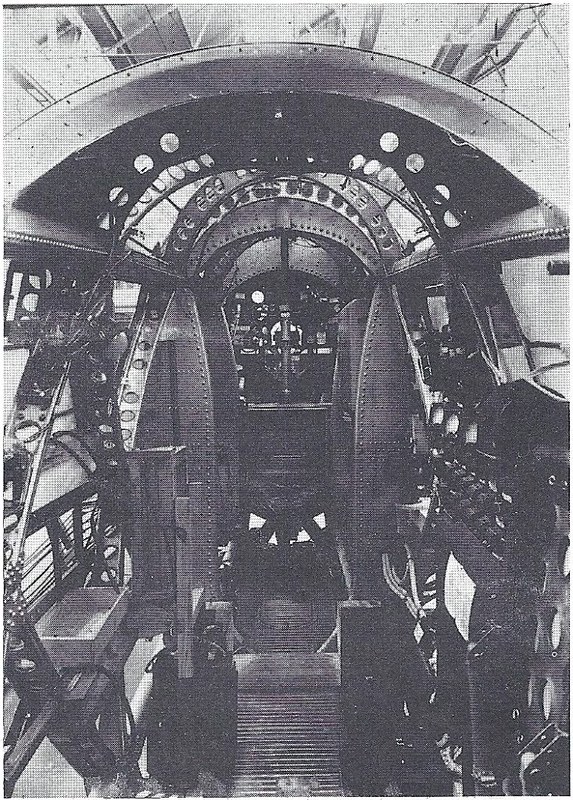

The unusual configuration of the Wellesley often confuses the casual observer. The canopy over the gunner's position looks a little like a "second cockpit" and some people assume the aircraft could be piloted from there, serving as a two-seat trainer aircraft. In fact, Vickers had designed a complete "drop-in" set of modules and controls, complete with a new fixed windscreen but otherwise open cockpit, to allow for the aircraft to be converted to just that purpose (described and illustrated in the Wellesley's service manual, AP1524A). However this seems to have been rarely, if ever, used. On the standard Wellesley the position was devoted to the gunner. Behind the gunner's position was the radio equipment and connecting the gunner and pilot positions was a cabin that could accommodate a third crewman (although there was no proper seat provided) who could operate as observer/navigator from that position or move forward to a position under the pilot where a set of windows looked forward under the engine and a hatch with a Mark IX bomb-sight enabled him to perform the duties of bomb-aimer. Although crude and cramped by modern standards the Wellesley was quite luxurious compared to the earlier generation of biplane aircraft.

The view looking forward to the pilot's position with the pilot's seat folded back so that you can see the instrument panel. Below the pilot is the bomb-aiming position with its window. Note the geodetic construction.

Volunteers from RAF groundcrew served as gunners, bomb-aimers and wireless operators having done fairly rudimentary courses, often they would have trained in multiple roles. They only flew as and when required and would be expected to do their full ground-based duties as well. There were no specialised navigators in RAF squadrons in 1937; navigation was seen as the pilot's responsibility, with all pilots being trained in it. Of course, up in his cockpit, the pilot could not plot maps, use a drift sight or take sun or star shots. So it was quite usual for a second pilot to be carried to do the navigation and in the 1930s RAF bomber squadrons would have up to double the expected complement of pilots specifically to carry out this task. It may be this fact, that the Wellesley often carried two pilots, that has led some to assume that the Wellesley had two positions it could be piloted from. In late 1938 the first newly qualified "air observers"⁴ began to reach bomber squadrons. These were initially airmen (later elevated to NCO rank) trained in rudimentary air navigation to help the pilot, as well as being trained in bomb aiming, air gunnery and wireless operation.⁵

The rear gun position of the Wellesley showing a Lewis gun with magazine fitted. By the start of WW2, the Lewis gun had been replaced by the Vickers "K" gun in RAF service in the UK and Northern Europe but it continued to be used in the Middle and Far East.

Into Service

The first Wellesley to be given over to the RAF (K7714) arrived at No 7 Squadron in early 1937, followed by K7715, K7716, K7717 and K7718. The last four aircraft formed "B" flight of No 7 Squadron which was separated off to form the nucleus of the newly reformed No 76 Squadron at Finningley which went on to be the first squadron fully equipped with the Wellesley. K7714 was passed on to 148 Squadron. The pace of re-equipment achieved in 1937 was remarkably good. By March of 1938 Bomber Command boasted no less than 5 Wellesley squadrons. Numbers 76, 77 and 148 with No 3 Group based at Finningley and Scampton and numbers 35 and 207 with No 2 Group at Worthy Down.

Wellesley K7733 in flight. The lines of markings on the wings are a series of black "footprint" stencils to show the groundcrew where they could safely walk leading out to the fuel tank filling points. Their Flight Sergeant would not take kindly to any "erk" putting their foot through the wing's fabric covering!

When only the first few Wellesleys had been delivered it was thought necessary to strengthen the wings and this strengthening was incorporated from the 9th production airframe, with the earlier aircraft being modified retrospectively. In early service, the Wellesley was plagued by problems with the main undercarriage collapsing if a heavy landing was made. There was a weak trunnion at the top of the undercarriage strut and a heavy landing could cause it to shear, this pushed the undercarriage strut up through the wing, taking the wing-mounted fuel tank with it. This was a particular problem in the first few months of the Wellesley's career, while the crews got used to handling the new aircraft and before a stronger trunnion could be fitted. Problems were also experienced with the doors for the bomb panniers, they were stiff to operate (although connected by hydraulics they required the manual strength of the operator to use them). The bomb pannier doors in the open position also caused vibrations in the aircraft when used as a dive-bomber (yes, such a huge aircraft as the Wellesley could be used as a dive-bomber, albeit not at the very steep angles of dedicated dive-bombers such as the Ju87 "Stuka" or Blackburn Skua). The solution to the problem was found to be simply removing the doors from the panniers altogether. Tests showed that their deletion made no difference to the speed or performance of the Wellesley.

On 5th July 1937 the famous test-pilot Jeffrey Quill had a lucky escape when Wellesley K7737 he was testing went out of control, he managed to parachute to safety.⁶

The wreck of Wellesley K7737. A full report on the crash can be found on the Aviation Safety Network website at <this link>.

In the 1930s, there were far more crashes and loss of life from flying than would be acceptable today (for example in 1937 alone the RAF suffered 153 fatal casualties from 93 separate incidents) and the Wellesley was no exception. But three incidents in the UK during 1937-1938 do stand out as being particularly tragic. On 25th October 1937, three crewmen on RAF Wellesley K7738 of 35 Squadron were killed when it crashed near Spilsby in Lincolnshire, seemingly having lost its way in fog. Then on 24th February 1938, a Wellesley of the Long Range Development Unit with three crew members on board went missing on a navigational training flight around Britain (more on this incident below). Then on 18th October 1938, two Wellesleys collided in mid-air during a training exercise over Great Dunmow in Essex, with the loss of all 6 crewmembers.

Another view of Wellesley K7733.

Differences in Wellesley configuration.

The first Wellesleys off the production line (the first 25 or so) retained the tail-wheel "spat" of the prototype. They also had a more rounded top to the rudder and the gunner's canopy did not have a "notch" cut-out at the rear. Later Wellesleys did away with the spat, had a rudder with a more "flattened" top and featured a notch in the gunners canopy, presumably to allow the gun to protude when the canopy was closed. Some of these features were fitted to the earlier Wellesleys during repairs or overhauls.

A photo of early Wellesleys, identified by the spatted tailwheel and rounded top to the rudder.

Many of the Wellesleys on the first production batch (K7713-K7791) had an extension to the front canopy, this seems to have also involved the fitting of a permanent large circular direction-finding (DF) loop. In descriptions, this extension is often described as having spanned the space between the front and rear canopies. It did not, it stopped just short of the rear canopy and the form and mechanism of the gunner's canopy were unchanged. The modification also introduced smaller windows above the existing ones on either side of the fuselage. What the purpose of this extension was is a bit of a mystery. The geodetic structure under the canopy extension was unchanged except for the fabric covering being removed. It would have allowed the third crewman to stand upright, sticking his head up through the geodetic frame, which might have been a relief from the cramped confines of the Wellesley on long missions. This extended "greenhouse" would have been a distinct disadvantage in the scorching heat of the Middle East and it seems that the extended canopy was never fitted to any aircraft of the second production batch of Wellesleys (L2637-L2716).

Wellesley with extended front canopy. These were only fitted to some aircraft in the first production batch.

The rear gunner of a Wellesley poses with his Lewis gun (albeit without a magazine fitted). Note the notch at the rear of the gunner's canopy. The fold-down side panel to the pilot's cockpit is very similar to that on the Vickers Supermarine Spitfire. The protruding rod coming out of the fuselage, underneath the roundel, is a tube down which a trailing wire aerial could be extended.

Record Breaker

In the 1930s long-distance record-breaking flights were very much in vogue, capturing the publics imagination all over the world. There was competition to be the first to fly certain routes and to do it in the fastest possible time. But one of the most sought-after records was that of flying the longest distance in one go, without having to land to refuel. In February 1933 the RAF had broken this record with a flight, in a specially-built Fairey monoplane, from the UK to South Africa (5,309 miles, 8544 km) only to see it taken later that same year by a French aircraft flying from New York to Syria. Then in 1937, the Soviets gained the record with a flight of 6,306 miles (10,148 km) from Moscow to California over the North Pole. The Japanese flew a longer distance still (7,239 miles, 11,650 km), in May 1938, but this was going around a closed-circuit around Japan numerous times, taking off and landing at the same place and always within easy distances of landing grounds. Even so, they had to have three attempts before they achieved it.

With the Wellesley, the RAF had an aircraft that had the potential to break the point-to-point record. The combat range of the Wellesley (with a bomb-load released at the mid-way point ) was some 1,300 miles (2092 km). However, the geodetic structure of the Wellesley gave ample space for extra fuel-tanks and it was hoped that refinement in the engine would cut fuel consumption to bring the record within reach. So three Wellesleys (K7717, K7734 and K7735) were modified for long range flight and issued to 148 Squadron for initial tests. The Wellesleys were modified to carry three times the fuel of the normal Wellesley, the undercarriage being strengthened to support the extra weight. A jettison system was also fitted to allow for the fuel to be got rid of quickly in the event of an emergency landing. At least one of the aircraft was fitted with a special Bristol Pegasus XXII "LR" engines that ran on 100 octane fuel and had its supercharger modified to give maximum fuel economy at cruising altitude. The engines were mated with new, constant speed propellers and housed in NACA cowls that were, in turn, merged to the lines of the fuselage for extra drag reduction. The aircraft also had a rudimentary autopilot fitted. These aircraft were given the Vickers type number 292.

Two photos (above and below) of Wellesley K7717, the test-bed for the Pegasus XXII LR engine. Note the full "NACA" engine cowl (rather than the simple Townend ring fitted on standard Wellesleys) mated to the fuselage with a streamlined fairing. Despite being an early production Wellesley the modifications seem to have included fitting the later-type flattened rudder and removing the tailwheel spat, although it retains the early-style gunner's canopy without a "notch". K7717 did not itself take part in any record-breaking flights. It was at first issued to 148 Squadron (hence the number on the side of the fuselage). It is not clear if the other 148 Squadron long-range test aircraft, K7734 and K7735, were also fitted with the Pegasus XXII LR engine.

With the concept proved, another four later production Wellesleys in the "L" series (L2638, L2639, L2680 and L2681) were modified with the full Pegasus XXII LR and joined the earlier "K" series aircraft in a new unit, spun-off from 148 Squadron, named the Long-Range Development Unit (LRDU).

To test how to get the most out of their new equipment the LRDU began flying a series of exercises to work out the best operating procedures and crew arrangements. It was during one of these test flights, on 24th February 1938, that Wellesley K7734 with a three-man crew disappeared without a trace. The mystery of the vanished bomber gripped the nation, with the BBC radio and newspapers requesting any sightings of the aircraft be reported to the authorities. Fears that this new monoplane bomber had somehow been hijacked by a foreign power were even expressed in Parliament. The following March, a tailwheel identified as being from the missing aircraft, was washed ashore in Norway, indicating it must have crashed into the North Sea. The fate of the aircraft had caught the public's imagination and in 1939 the film "Q Planes" featured a storyline based upon mysterious disappearances of prototype aircraft.

During these long-distance test flights, a crew arrangement was settled upon. The crew of each aircraft would be composed of two pilots and a wireless operator. The pilots were all experienced navigators while the wireless operators were also given a course in navigation. In turn, the pilots were instructed on the use of the wireless equipment, especially on taking radio direction "fixes". The use of the autopilot and the fact that the Wellesley's pilot seat could be swung back enabled the two pilots to swap places and share flying duties. A rudimentary bunk was fitted in the bomb aimer's position to allow the crew to take turns trying to get some sleep.

LRDU Wellesley

On the 7th July 1938, 4 Wellesleys of the LRDU (L2638, L2639, L2680 and L2681) took off on a long-distance proving flight from RAF Cranwell. The flight took them to Ismailia in Egypt, then on to Basra in Iraq, then on to Kuwait and down the Persian Gulf before turning back to land at Ismailia. They covered 4,370 miles (7,032 km) in 32 hours 32 minutes. The longest flight by aircraft in formation up until that time. The aircraft returned to Britain on 21st July 1938.

For the attempt to break the world distance record, a route from Ismailia in Egypt to Darwin in Australia was chosen. The route went over territories that would not present any diplomatic problems and would also demonstrate Britain's ability to reinforce its assets in the Far East. The runway at Ismailia had to be lengthened to enable the heavily laden Wellesleys to take off. To save weight the crews did not take any parachutes with them, and all oxygen equipment was stripped from the aircraft. On the 5th November 1938, three Wellesleys took off from Ismailia for the attempt. Two of the aircraft (L2638 and L2680) landed at Darwin on the 7th November having flown the 7,175 miles (11,547 km) from Ismailia in 48 hours 5 minutes. The third aircraft (L2639) ran short of fuel and had to land on the island of Timor, but even that was still more than the existing Soviet distance record. It refuelled and quickly rejoined the other two aircraft at Darwin. This was a huge success for the RAF, featured prominently in the newsreels and newspapers of the times.

All three aircraft then did a "flag-waving" tour of Australia. Sadly two of the aircraft crashed in the course of the tour, one of these (L2639) had to be abandoned where it had crashed (it was later retrieved and used as an instructional airframe by the RAAF). The other crashed Wellesley (L2638) was dismantled and sent back to the UK by sea. The remaining airworthy Wellesley (L2680) was also shipped by sea but to Egypt.¹º

The Wellesley goes overseas.

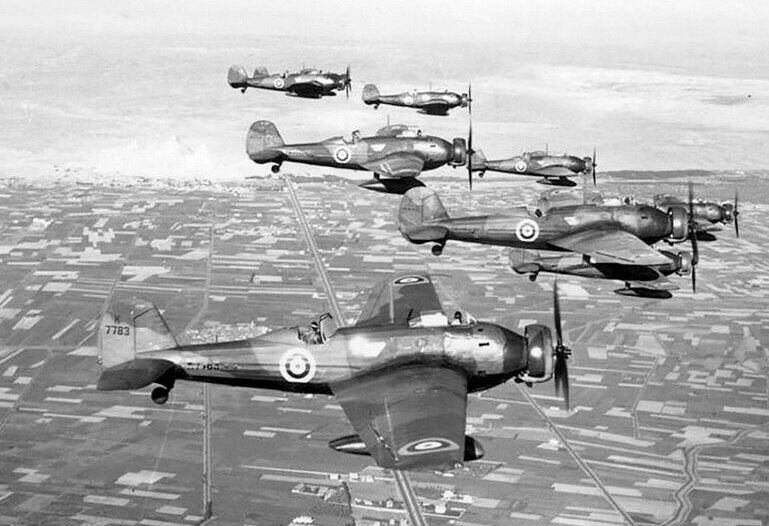

Wellesleys of 45 Squadron make an impressive sight over Egypt's fertile Nile delta.

The Near East and East Africa was where the majority of Wellesleys ended up. The original production order for 96 Wellesleys had been followed by an order for an additional 80, making a total of 176 production Wellesleys (excluding the prototype). These had served Bomber Command well during 1937-38. But they were quickly phased out by the more capable new Blenheims, Whitleys and Hampdens. Even the Fairey Battle eclipsed the Wellesley in speed. Of course, the Wellesley's "big brother" the Vickers Wellington which shared its geodetic design and replaced it on Vicker's production line, went on to form the bulk of Bomber Command's strength during the early to middle war years. So even though it had only been in service for a couple of years the Wellesley was deemed obsolete for the European theatre and they were shipped out to equip four squadrons operating in the Near East and Africa.

One big benefit of having shared much of the fuselage design with the G4/31 biplane was its built-in suitability for the hot and dusty conditions in these enviroments and increased chance of survival if crash-landed in the desert. It had a large 6-gallon water tank along with individual water bottles and a condenser to capture moisture from the night air. It had space for a supply of rations and had a toolkit for running repairs. A telescopic aerial could be carried that could be erected in the event of a crash-landing to increase the chance of using the radio to call for help. To keep the radio powered, once the batteries ran down, it even had a hand-cranked generator. The radial Pegasus engine was especially suitable for hot dusty conditions with a "Serck" oil-cooler designed for tropical conditions. The carburettor air intake could be easily protected from sand and grit by a box-like "Vokes" air filter. Both the pilot's and gunner's canopy could be left open to prevent the "greenhouse" unbearable conditions experienced by more modern multi-engine designs with enclosed turrets and fixed canopies. The stretched fabric that provided much of the surface area of the Wellesley did not absorb or retain heat in the way that a purely metal airframe did, making it more comfortable to operate and maintain (the burning heat of the desert sun would make it impossible to touch the surface of a metal aircraft left out in the open). One other hangover from the G4/31 design was the ability to mount a "message-hook" under the fuselage. This could be used to pick up messages suspended between two poles on the ground. However, this does not seem to have ever been used; the paragraphs about it's installation were crossed out of the Air Ministry Wellesley maintenance manual (AP1524A) as part of an official amendment before April 1939, suggesting its use was dropped before the start of WW2.

The first squadron outside the UK to receive Wellesleys was number 45 Squadron based at Helouan (Cairo) and Ismalia in Egypt. The Wellesleys replaced the squadron's Vickers Vincent biplanes in November of 1937. One of the tasks undertaken by the Wellesleys was a weekly mail run from Egypt over to Gaza in Palestine. In June 1939, the squadron converted to the Bristol Blenheim twin-engined bomber.

Number 14 Squadron based at Amman in Transjordan (modern Jordan) was the second to operate Wellesleys outside the UK, swapping its Fairey Gordons for Wellesleys in March of 1938. At the time there was serious unrest between the Arab and Jewish populations in nearby Palestine. The Wellesleys were used to patrol the coast of Palestine in search of ships bringing in Jewish refugees from Europe and gun runners bringing in weapons for the various factions. In October of 1938, the squadron started supporting the "Special Night Squads", organised by Orde Wingate, by dropping flares and small bombs. In August of 1939, the squadron moved to Ismailia in Egypt.

The third overseas squadron to convert to the Wellesley was number 223 Squadron based at Nairobi in Kenya which swapped its Vickers Vincent biplanes for Wellesleys in June 1938. This squadron seemed to go through a period of bad luck, losing four Wellesleys to accidents in quick succession. One tragic incident occurred on the 22nd of July 1939 when Wellesley L2671 plunged into the ground during a flying display at Nairobi, killing the two-man crew. The squadron left Kenya for Sudan in September 1939.

The last overseas combat squadron to receive Wellesleys was number 47 Squadron based at Khartoum in Sudan. It started operating Wellesleys in June 1939 but kept a flight of Vickers Vincent biplanes operating alongside the Wellesleys until August 1940.

At least one Wellesley also saw pre-war service with the Khartoum Communications Flight in Sudan, flying transport and mail-carrying missions.

As tensions in Europe rose, the threat of war with Italy loomed. To be in a position to counter the threat from either Libya or Italian East Africa, the three remaining Wellesley squadrons were bought together in Egypt and Sudan. Without a bombload, the Wellesley demonstrated a remarkable ceiling of 33,000 feet (10,058 metres). To put that into perspective its "big brother" the Vickers Wellington had a service ceiling of only 18,000 feet (5,486 metres), while even the Avro Lancaster could only do 24,500 feet (7,468 metres). This was due to the Wellesley's combination of huge wing and supercharged Bristol Pegasus engine. The Pegasus had been used on the aircraft that first flew over Mount Everest in 1933 and had powered many of the aircraft that gained the world altitude record in the 1930s, including the Bristol 138. The standard Wellesley had full oxygen equipment for the crew and could be equipped with a "F24" camera for aerial photography. So the Wellesley would have been the ideal "spy plane" for the late 1930s. It is hard to believe that during the period until Italy joined the war that the occasional training flight by a Wellesley did not "accidentally" stray over Libya or Italian East Africa with their cameras running.

The Wellesley goes to war.

War began in Europe in September 1939. Over the following winter and spring all available Wellesleys in the UK were ferried out to Egypt, flying out via France and Malta. There was tragedy on 4th April 1940 when a flight of 4 Wellesleys ran into a storm over the French coast and two of the aircraft were lost, along with 6 crewmen. The squadrons of Wellesleys in Africa were not involved in conflict until 10th June 1940 when Italy entered the war on Germany's side. Italian colonies in Libya and East Africa were adjacent to British territories in Egypt, Sudan, Kenya and British Somaliland.

If you were a totalitarian dictator in the 1930s and wanted to set yourself up with a military base in the best strategic position to bring down the British Empire in the event of war you would be hard put to find a better place than the Italian possessions in East Africa, comprising Eritrea, Italian Somaliland and Abyssinia (Ethiopia). With sufficient force there, you could command the Red Sea and access to the Suez canal, interdict oil shipments from the Persian Gulf, threaten Kenya and Sudan, and via Sudan, Egypt. What would the Japanese have given to refuel their aircraft carriers at Massawa on the Red Sea Coast? What would Rommel have given for a drive, by troops and tanks supported by aircraft, up through Sudan to Egypt at the same time as his Afrika Corps advanced from Libya?

If you were a totalitarian dictator in the 1930s and wanted to set yourself up with a military base in the best strategic position to bring down the British Empire in the event of war you would be hard put to find a better place than the Italian possessions in East Africa, comprising Eritrea, Italian Somaliland and Abyssinia (Ethiopia). With sufficient force there, you could command the Red Sea and access to the Suez canal, interdict oil shipments from the Persian Gulf, threaten Kenya and Sudan, and via Sudan, Egypt. What would the Japanese have given to refuel their aircraft carriers at Massawa on the Red Sea Coast? What would Rommel have given for a drive, by troops and tanks supported by aircraft, up through Sudan to Egypt at the same time as his Afrika Corps advanced from Libya?

Wellesley L2645. Note that a portion of the wing root folded out to form a set of steps to allow easy access onto the wing.

The Italians had massive forces in their colonies in East Africa. An army of 290,000 men (371,000 after mobilisation) with medium tanks, tankettes and armoured cars, an air force of 323 aircraft with 23 bomber squadrons and 4 fighter squadrons, a naval force of 9 destroyers, 8 submarines and a squadron of torpedo boats. The British had a pitifully small force to oppose them, only 9,000 men in Sudan, another 9,000 in Kenya and 4,500 in British Somaliland with no armour and very little artillery. However, amongst the collection of old biplane aircraft available to the British were the three squadrons of Wellesleys (Nos 14, 47 and 223) and these were to have a profound effect on the conflict.

The three Wellesley squadrons were concentrated in Sudan as "254 Wing". British concerns were centred on the Italian threat to their supply line to Egypt, so the Italian Navy base at Massawa and the associated Italian bomber bases were seen as the best targets. The British were meticulous in their planning to strike these and reasoned that an attack at sunset would give the best chance of success, with the aircraft flying in from the east they would be almost invisible against the twilight sky while the target would still be illuminated by the sun sinking in the west. Hence they delayed their strike until sunset on the second day of hostilities (11th June). The attack by 14 Squadron must rank as one of the most strategically successful bomber raids of any war. Rather than go for the obvious target of ships and aircraft, instead, they went for the fuel tanks on the edge of Otomlo airfield near the navy docks at Massawa. Attacking in 3 waves from only 500 feet the Wellesleys destroyed the fuel tanks and also did considerable damage to buildings and aircraft on the airfield. One estimate puts the quantity of fuel destroyed as high as 350,000 gallons. This put the Italian Navy on the back foot from the very start of the war and the need to conserve their dwindling stocks constrained their operations for the rest of the hostilities. All of 14 Squadron's Wellesleys returned safely from this raid, although one was delayed. Having lost its way in the dark it was landed on a beach where the crew spend the night before taking off and returning to base the following morning.

Earlier on the same day, 47 Squadron struck the airfield near the Eritrean capital Asmara, losing one aircraft to anti-aircraft fire. The following day the third of the Wellesley squadrons, number 223, struck the Italian airfield at Gura doing extensive damage. This was to be the first of many raids on this important target. They were intercepted by Italian CR42 fighters who severely damaged one of the Wellesleys, which together with another hit by AA fire, crash-landed on their return to base. In return, the gunners of 223 Squadron claimed a CR42 shot down and others damaged. That same day 47 Squadron returned to Asmara, striking the airfield again.

Bombs bursting on an Italian airfield, probably Asmara.

And so it continued, day after day the three Wellesley squadrons would attack airfields, port and fuel installations and also flying convoy protection patrols over the Red Sea. They often encountered Italian fighters. The older CR32 fighters would struggle to catch the Wellesleys unless they had a height advantage, but the newer CR42s were a potent threat if encountered. To give extra firepower the Wellesleys were up-gunned, The gunners position was often modified to accept two guns, rather than one, and machine guns were set up to fire downward through a hatch in the floor, then 14 Squadron worked out a modification (built for them at the Sudan Railway workshops) to allow guns to be mounted on the side windows. When this was fitted the Wellesley often flew with a four-man crew, pilot, bomb-aimer, "beam " gunner and top gunner. The extra gunners were often volunteer cookhouse, orderly or admin staff.

It was one of these "up-gunned" aircraft that shot down a Savoia-Marchetti SM81 "Pipistrello" bomber of 10a Squadriglia over the Red Sea on 8th July. The Wellesley had first exhausted all the ammunition for its forward-firing gun on the bomber before drawing alongside to let its gunners finish it off.

A Wellesley fitted to be able to fire machine guns through the side windows of the fuselage. Note also the rear gunner's position has had a second gun fitted. This is one of the Wellesleys with the elongated front canopy and a DF loop mounted. These aircraft are sometimes mistakenly called the "Wellesley Mk II" but there never was such a designation.

The Italians had launched a two-pronged attack into Sudan on the 4th July, capturing the fort and railway junction at Kassala and the fort at Gallabat further south. The Wellesleys flew missions against troop movements and bombed the fort at Kassala after it had been captured. After this rather small advance, the Italians adopted a defensive posture on the front with Sudan.

British intelligence became aware that the Italians were ferrying supplies into their East African territories by air from Libya, flying across Sudan at night. Of particular concern was the use of large Savoia-Marchetti SM82 aircraft, able to carry an entire disassembled CR42 fighter within its capacious fuselage. On the night of 18th July 1940, the Wellesleys of 14 Squadron were given the task of bombing the airfield at Agordat where a detachment of Italian supply aircraft was expected to arrive the following morning. This they did, claiming to have badly damaged two aircraft and many of the airfield buildings. But Italian supply flights continued. In August the British discovered that Italian aircraft were refuelling for these supply flights at a secret airstrip at Jubel Uweinat in a remote location in the extreme south of Libya near where the borders of Libya, Sudan and Egypt meet. This landing ground was attacked by Wellesleys on 26th August with guns, bombs and the dropping of metal caltrops to shred the tyres of any aircraft trying to use it. A flight of 7 ½ hours over hostile desert terrain being required to complete the mission.⁷

Wellesley over mountainous terrain.

On the 3rd August, the Italians invaded British Somaliland. Outnumbered and surrounded on three sides, the British Garrison there fought a delaying rearguard action, retreating to the port of Berbera for evacuation by sea. To support them No 223 Squadron was sent to operate from Aden and Perim Island on the other side of the Gulf of Aden. On the 18th August, 223 Squadron launched an attack on the airfield of Addis Ababa, the capital of Abyssinia. This highly symbolic raid was a complete success, destroying numerous aircraft and three hangars. The Wellesleys were engaged by CR32 fighters but despite suffering damage, they all returned without casualties to base (one of the five aircraft involved got lost and landed in French Somaliland but took off again before the crew could be interned).

Attack on an Italian airfield in East Africa, the aircraft are likely Caproni Ca 133s

Following the evacuation of British Somaliland, 223 Squadron rejoined the other Wellesley squadrons in Sudan. The Wellesleys continued their raids against not only strategic targets in Eritrea but also against tactical targets within the Italian incursion around Kassala. It was the continued efforts to hit the strategic targets that had the most effect, targeting fuel and ammunition dumps and so badly degrading the Italian's abilities to fight. The petrol supplies at the airfield at Gura were a target that received repeated raids, as was the nearby Mai Edaga works of the Caproni aircraft company. While Bomber Command in the UK struggled to find and bomb targets in the cloud and industrial haze of Europe the Wellesleys in East Africa had surprising success in finding targets in the clear skies of Africa. Raids on moonlit nights began to be a favourite of Wellesley crews. With the Italians having no night-fighters there was little point in carrying a dedicated gunner so night missions were usually flown by two-man crews. One example of such an attack was on the night of 28th-29th August 1941 when a Wellesley attacked the headquarters of the Italian Air Force near Massawa, by moonlight, causing extensive damage.

But Italian CR42 fighters continued to be a persistent foe to the Wellesleys and a slow trickle of casualties on daylight bombing raids continued. In November No 14 Squadron replaced its Wellesleys with twin-engined Blenheim bombers. This left just 47 and 223 Squadrons flying Wellesleys against the Italians. On the 16th October 1941, No 47 Squadron suffered a major setback when eight of its aircraft were destroyed at a forward airfield at Gerdaref by strafing Italian CR42 fighters. However, the RAF had good stocks of replacement Wellesleys and the losses were made good within a few days.

On the 20th -21st October 1940, the Italian Navy ventured out to attack Convoy BN7 in the Straits of Mandeb. A patrol by three Wellesley from 47 Squadron was part of the British response and one of the Wellesleys delivered an attack on one of the Italian destroyers, claiming direct hits. It seems the destroyer was beached following a battle with HMS Kimberley; it is not clear if this was before or after the claimed Wellesley attack. Most sources attribute its loss to attack by Blenheims of 45 Squadron, this was certainly delivered after the destroyer was beached. This was the last time the Italian Navy would attempt to attack a British convoy in the Red Sea by surface action.

On the 6th November 1940, Indian and British forces launched an attack to retake the fort at Gallabat. To support this attack, Wellesleys launched raids on Metemma over the border from Gallabat in Abyssinia.⁸ On the 16th November a detachment from 223 Squadron based at Perim Island, off Aden, flew a night attack on the Italian airfield at Gura. To add to the pressure on the Abyssinia front the Wellesleys attacked Danglia twice at the end of November. This was followed up by an attack on Bure on 6th December. This last attack resulted in the loss of one Wellesley to a CR42 fighter, the first Wellesley combat loss since the Gallabat action started.

Throughout December the Wellesley raids on the Abyssinian front continued, aimed at hampering Italian efforts to reinforce Metemma and providing inspiration for Abyssinian partisans. On the 15th December, the southern offensive by Nigerian and South African troops in Italian Somaliland began. While the attack on Metemma had diverted Italian attention to Western Abyssinia the big British attack was planned to strike Eritrea. This began in January 1941. By this time the RAF in Sudan had been reinforced with Blenheim and Hurricane squadrons. During January, Wellesley squadrons switched to night attacks, either on targets in Eritrea or longer-range strikes into Abyssinia. The British attack in Eritrea was a huge success and by February the Italians were in retreat. With a decrease in Italian fighter and AA opposition, the Wellesleys returned to daylight raids, but this may have been premature as two Wellesleys of 47 Squadron were lost on the 7th February.

Wellesleys also provided support for Gideon Force, under Orde Wingate (later leader of the Chindits) in their campaign into Abyssinia. They dropped supplies to the force, losing one Wellesley during one such mission in December. On at least one occasion Wingate flew in a Wellesley himself. The Ethiopian emperor, Haile Salassie, was also reported to have flown in a Wellesley.

Mai Edaga, in the centre of Eritrea, along with the adjacent airbase at Gura, was one of the centres of operation of the Italian Air Force. It had been constructed in the 1930s for the invasion of Abyssinia. The Caproni aircraft company had set up workshops there for the overhaul and repair of both airframes and engines; as such, it was of vital importance to the Italians. It had received numerous raids from the Wellesley squadrons earlier in the war but now it was decided to give it special attention. It received a night raid on 14th/15th February by three Wellesleys of 223 Squadron, one of which failed to return. The following morning a Wellesley of 47 Squadron with an escort of four Hurricanes did a recce of the base, the Hurricanes taking care of the CR32 fighters that took off in response. Then the following day the Wellesleys returned in force with 47 and 223 Squadron combined putting 18 Wellesleys over Mai Edagar in a raid that reportedly destroyed the workshop facility.

The raid on Mai Edaga 16th Feb 1941, showing the hits on the Caproni workshops.

By March the invasion of Eritrea reached a critical point. The twin thrusts, one from Kassala and the other down the Red Sea coast having converged on the Italian positions at Keren, the key to the approaches to both the port of Massawa and the capital Asmara. From 15th March, both 47 and 223 Squadron strove to put in as many sorties as possible against the Italian defences in what was called the "Keren Blitz". Over the next few days, furious air battles raged over Keren as the Italians, realising the critical nature of the battle, put up CR32 and CR42s against the Wellesleys. They shot down one Wellesley and damaged others but were in turn victims of the Hurricane escort. One Wellesley using the captured Italian airfield at Agordat was destroyed by a strafing Italian fighter. The air battle reached a peak on the 31st March when 8 Wellesleys joined 11 Lysanders, 10 Hardys, 8 Gauntlets and a Vincent in a "grand strafe".

The wreck of Wellesley K7715 "KU-H" after crash-landing at Agrodat following damage by Fiat CR42 fighters during a bombing raid on Keren. The burnt-away fabric reveals the underlying geodetic construction of the wing. The Wellesley is one of those modified with an extended "glasshouse" from the front cockpit canopy and a direction-finding "DF" loop. You can clearly see the notch in the rear of the gunner's canopy. One fine detail, you can just about make out on this picture, is where tape covering the cable that ran to the dinghy stowage ran; down the top forward leg of the "K" to the wing and then across it at the front of the burnt-out section.

With the Battle of Keren won, Asmara fallen and landings in British Somaliland to liberate Berbera, it was only a matter of time before the strategic port of Massawa fell. On the 31st March, three of the remaining six Italian destroyers in the port were sent out on a one-way "suicide mission" with orders to run north up the Red Sea and attack the Suez Canal, sinking themselves as block-ships in the mouth of the canal if possible. The sortie was abandoned when one of the destroyers ran aground almost as soon as it left port. On the 2nd April, the Italians sent the remaining five destroyers on a much less ambitious plan to bombard Port Sudan and then scuttle themselves. They were attacked by FAA Swordfish and RAF Blenheim bombers, sinking two of the destroyers. Another two destroyers, Pantera and Tigre, were attacked by Wellesleys of 223 Squadron. Although no hits were obtained the two destroyers ran themselves aground on the eastern shore of the Red Sea, where the Wellesleys of 223 Squadron returned to finish them off with bombing. Apparently, one of the Wellesleys was hit by return fire from the destroyers and had to make a forced landing on the coast of Saudi Arabia, another Wellesley landed nearby in an attempt to rescue the crew but was itself damaged on landing, leaving both crews having to be picked up by the Royal Navy. The remaining Italian destroyer afloat was abandoned and scuttled.

In early April 1941, 223 Squadron moved up to Egypt to convert to flying the Martin Maryland twin-engined bomber. This left 47 Squadron as the RAF's only Wellesley unit. By this time great advances had been made by the thrusts into Italian East Africa and Addis Ababa was captured on 6th April. The Italian army retreated to mountain strongholds with the forlorn hope that a German/Italian victory in the Western Desert would come to their aid. Number 47 Squadron had moved to Massawa, operating out of the aerodrome they had so often bombed in the past. The squadron continued operations against the Italians, principally against Gondar which was the largest of the Italian strongholds and the only one that still had elements of the Italian Air Force flying from it. Not only did they fly bombing missions, but they also dropped supplies to the Indian, South African, British and partisan forces surrounding Gondor. The last Wellesley lost to an Italian fighter was on 2nd July (another was slightly damaged on the 9th July). The last casualties of 47 Squadron came on 14th November when a Wellesley crashed on a recce mission (not due to enemy action). The last flight by an Italian aircraft in East Africa, a ground-attack mission by a CR42, was as late as 20th November 1941. The battle for Gondor was hard-fought. Number 47 Squadron flew its last combat mission in East Africa on the 27th November with a raid by 6 Wellesleys on Gondor in conjunction with Hawker Hartebeests and P-36 Mohawks of the South African Air Force. The same day Gondor finally surrendered.

Anti-submarine patrols and contribution to breaking the Kriegsmarine's "Triton" Enigma cypher.

Between April 1942 and February 1943, Wellesleys performed an important stop-gap role flying convoy escort and anti-submarine patrols in the Eastern Mediterranean. It was 47 Squadron, which moved up from East Africa, that undertook this role but it operated well below squadron strength and so was restyled "47 Squadron Air Echelon". Royal Navy Observers were assigned to serve with the squadron to help with navigation over the sea and identifying ships. The aircraft were armed with four depth charges (2 in each pannier). Flying from primitive landing grounds in Egypt and Palestine, the Wellesleys carried out long patrols, often of up to 7 hours duration. It is unusual for a single-engine aircraft to have been used for maritime patrol duties of this kind and it is a testament to the amazing reliability of the Wellesley's Pegasus engine that no aircraft were lost at sea. During this period they carried out 7 attacks on German and Italian submarines. Although no submarines were sunk directly by these attacks, a Wellesley did participate (along with a Wellington of 221 Squadron) in the sinking of U-372 on 4th August 1942 in co-operation with Royal Navy destroyers.

There were dedicated Wellington and Sunderland maritime patrol bombers in the Eastern Mediterranean at the time. These were fitted with the early "stickleback" ASV radar that could sweep the area on both sides of the aircraft but was of less use in detecting vessels straight ahead. It could easily pick up a surfaced U-boat but did not have the resolution to pick up a periscope. It was only later in the war that the introduction of the higher frequency centimetric radar and Leigh-light searchlights enabled attacks on submarines at night. The Wellesleys seem to have sometimes operated in a "hunter-killer" relationship with the Sunderlands and Wellingtons. The larger aircraft operating at night would use their radar to detect the submarines running on the surface and then call in a Wellesley to search the area where the U-boat was expected to be at first light.

A Wellesley of 47 Squadron Air Echelon at Borg El Arab in Egypt. In the background on the left is a Vickers Wellington. You can just about make out the "stickleback" aerials of the early ASV radar running along the top of the Wellington's fuselage.

The most noteworthy contribution of a single Wellesley to the war came on 30th August 1942. The Submarine U-559 was spotted on radar by the crew of a Sunderland Flying boat. A Wellesley of 47 Sqdn Air Echelon was despatched to aid Royal Navy destroyers in hunting the submarine. The Wellesley spotted the sub and attacked with depth charges, these did not sink the submarine but the Wellesley then dropped a smoke float to mark the submarine's position which guided the destroyers to its location which led to a series of depth-charge attacks, aided by hydrophones and sonar that lasted some 16 hours. When the submarine broke the surface, its crew abandoned the boat without scuttling it. This allowed Royal Navy personnel from HMS Petard to board the submarine and retrieve the U-boat's code books. Unfortunately, Lt Anthony Fasson and Seaman Colin Grazier were still in the submarine when it sank. The information captured from the U-559 had a dramatic impact on the war, allowing Bletchley Park to understand the workings of the Kriegsmarine's M4 "4 -rotor" Enigma machine and then do regular decrypts of messages encoded with it for the rest of the war.

In early 1943, 47 Squadron converted to flying Bristol Beaufort torpedo bombers and were brought back to full squadron strength. They flew their last Wellesley mission (and probably the last RAF operational sortie by a Wellesley) on 28th February 1943.

Transport squadron duties

Several Wellesleys were officially on the strength of 117 Transport Squadron between April and November 1941 as part of the trans-Africa ferry service between Tokardi and Khartoum. They were used to transport mail or urgent spare parts, and act as navigation leaders for flights of single-engined fighters being sent along the route. They were also available to search for any aircraft that had to make an emergency landing. A single Wellesley was also on the strength of 267 Transport Squadron in Egypt, although records seem to show it was not used much. A Wellesley transported members of the top-secret "Way Mission" ⁹ to Mosul in Iraq in 1941. There are a number of incidents that show Wellesleys were being used for transport duties well into 1942. A Wellesley rescued the crew of a force-landed Bristol Bombay from French Equitorial Africa in 1942. There is a possibility the remaining long-range Wellesley from the record-breaking trip to Australia (L2680) was used for transport duties. It is claimed that, in January 1942, it was used to transport three pilots of 258 Squadron from Khartoum to Port Sudan, sitting one behind each other as in a rowing boat.¹º

Wellesley odds and ends

One early Wellesley off the production line (K7712) served as a test-bed for the powerful Bristol Hercules engine. The fitting of the big Hercules in a lengthened nose on this Wellesley gave it a more modern, streamlined look. It was allocated Vickers Type number 289. It was used by the Bristol Company and was then passed on to the Royal Aircraft Establishment. It survived until 1944.

Wellesley K7712, fitted with a Bristol Hercules engine.

Another Wellesley (K7740) was on the strength of the Torpedo Development Unit (TDU) at Gosport. It was used for trials of dropping torpedos at higher speeds and higher altitudes in preperation for the introduction of the Bristol Beaufort torpedo bomber. At this time the TDU was also running highly-secret experiments on a series of air-launched "stand-off" delivery systems. Details of these projects, some under the direction of the famous novelist Nevil Shute Norway, are very scarce. It is certainly known that the Wellesley participated in the testing of the "Toraplane", a glide-bomb that was designed to carry a torpedo. It is uncertain if the Wellesley carried one of these weapons itself or acted as a "chase-plane" to monitor their release.¹¹ You would have thought the long wingspan of the Wellesley would have been ideal for these types of experiments with a couple of the smaller glide-bombs or rocket prototypes slung under the wings in place of the bomb-panniers.

Wellesley K7740, used by the Torpedo Development Unit at Gosport. It features the extended canopy and additional side-windows but it is not carrying a direction-finding (DF) loop.

Wellesley Specifications

Engine: Bristol Pegasus XX, 950 hp

Range with 1,000 lb (453 Kg) of bombs (dropping them at mid-way point) - 1,300 miles (2092 km)

Speed: Maximum: 228 mph (367 kph), cruising 188 mph (302 kph).

Ceiling: 33,000 feet (10,058 metres).

Gun armament: One forward-firing Vickers or Browning machine gun in the starboard wing (the Vickers gun was fitted to the first 39 aircraft off the production line). One or two Lewis or Vickers "K" machine guns in gunners position. In East Africa supplemented by a machine gun firing through a hatch in the floor and others firing through the beam windows.

Bombload: Maximum bombload regularly flown 4 x 500 lb (226 Kg) bombs and an additional four 24 lb (11 kg) Cooper bombs or incendiaries.

Dimensions: Wingspan 74 ft 7 inches (22.73 metres). Length 39 ft 3 inches (11.96 metres).

Production: Prototype K7556. First production contract for 96 aircraft (Sept 1935) K7713-K7791 and K8520-K8536. 2nd production contract for 80 aircraft (Aug 1936) L2637-L2716.

Links

Wellesley Video on Ed Nash's Military Matters YouTube channel (cheers Ed!).

List of Wellesley crashes on the Aviation Safety Record Website (not all incidents recorded).

Page on Geodetic structure on the Barnes Wallis Foundation website. It includes a nice cutaway drawing of a Wellesley.

Wellesley Video on Ed Nash's Military Matters YouTube channel (cheers Ed!).

List of Wellesley crashes on the Aviation Safety Record Website (not all incidents recorded).

Page on Geodetic structure on the Barnes Wallis Foundation website. It includes a nice cutaway drawing of a Wellesley.

Notes

¹ To list the designs put forward for Air Ministry Specification G4/31 - Armstrong Whitworth AW 19 biplane (prototype flown), Blackburn B-7 biplane (prototype flown), Boulton and Paul P66 (project only), Bristol type 120 (prototype flown), also Bristol types 121, 122, 125 and 126 (projects only), Fairey G4/31 biplane (prototype flown) and also a monoplane (prototype not completed), Handley Page HP47 monoplane (prototype flown), Hawker PV4 biplane (prototype flown), Parnall G4/31 biplane (prototype flown), Westland PV7 high-wing monoplane (prototype flown). Also, of course, the Vickers type 253 biplane. The Air Ministry financed the building of the Vickers 253 biplane, the Parnall biplane, the Handley Page HP47 monoplane and the Fairey monoplane (it switched the financing to the Fairey biplane when the monoplane project ran into issues with its novel "arched" layout).

² For a full list of the seven tenders, their cost and lead-time, see Sidney Shail's "The Battle File" published by Air Britain.

³ For verification of this see Specification 22/35 in The British Aircraft Specification File by KJ Meekoms and EB Morgan (An Air Britain Publication).

⁴ The Fleet Air Arm had "observers" as well, but these were highly-trained specialists, skilled in both air and sea navigation, and experts in ship recognition and directing naval gunfire. They were not even in the "Air Branch" but allocated directly to the carriers or ships they served on. They were Officers or NCOs and usually had training and experience way beyond that of the RAF Bomber Command "observers". Pre-War, the pilots who served with Coastal Command benefited from a longer, more specialised, course in navigation than those who served in Bomber Command.

⁵ Since Bomber Command squadrons were ultimately judged on their performance in bombing competitions there was great competition between pilots (and indeed between squadrons) to secure the services of the best bomb-aimers, but navigation skills were not greatly fostered. As war approached the RAF began to realise just how poor its navigation was and a whole series of initiatives were run through in the years 1937 to 1942 to improve things. Unfortunately, some of the early actions (like sub-contracting out the training to civilian companies) made things worse rather than better. Dedicated aircrew trades, with minimum NCO rank when trained, were introduced. Observers ended up being given full responsibility for navigation and eventually, but only in 1942, the name was changed from Observer to Navigator. For a full understanding of this topic read "Observers and Navigators" by CG Jefford, ( ISBN 978-1-909808-02-7 ). Or, for a much shorter overview, read this pdf copy of an article from the "Tee Emm" aircrew magazine of March 1946 at <this link>.

⁶ There is a detailed description of this incident in Jeffrey Quill's autobiography "Spitfire - A Test Pilot's Story" ISBN 0 947554 72 6

⁷ The first SM82 flight to deliver a CR42 fighter to East Africa had occurred on the 24th August 1940. They would continue to be flown into 1941 with a total of 51 CR42s being delivered by air. This was even though only two SM82 aircraft were modified to carry the CR42. The Italians also operated SM75 and SM83 aircraft on these supply missions as well as delivering replacement bomber aircraft along the same route. The long-range SM82, 83 and 75 did not need to use secret landing grounds to refuel, they were quite capable of flying to East Africa directly from Benghazi. In fact, an SM82 had gained the long-distance record in 1939 with a flight of 8,038 miles, albeit it was over a closed circuit (flying in circles) so in a different class to the Wellesley's 7,162-mile point-to-point record which stood until 1945 when it was beaten by a flight of 7,916 miles by an American B-29 Superfortress.

⁸ Descriptions of the fighting at Gallabat and Metemma are often contradictory. British sources stress the initial retaking of the fort at Gallabat and then its denial to the Italians, while Italian sources stress the failure of the British to take Metemma. Some sources say British tactical air-support was generally good, playing a role in eliminating Italian artillery, while others say it was badly co-ordinated.

⁹ The "Way Mission" was a small team sent to Russia to coordinate the supply of equipment to the Russians via Iran. It was led by Colonel RE Way. Amongst its members was Edgar Harrison who set up a workshop to install British-made radios into Russian tanks and train Russian technicians in their maintenance. See the biography of Edgar Harrison by Geoffrey Pidgeon, published by Arundel Books. ISBN: 978-0-9560515-0-9. It's a really fascinating story.

¹º In chapter two of "Hurricanes Over The Jungle" by the wartime pilot Terence Kelly (ISBN-10: 1844151980, ISBN-13: 978-1844151981), he details being transported, with two other pilots of 258 Squadron, from Khartoum to Port Sudan in a Wellesley he says was one of those used in the long-distance record (presumably L2680). Amazingly, he claimed it was piloted by one of the record-breaking crew, Flt Sgt TD Dixon. This was in January 1942 when 258 Squadron was being ferried across Africa to try to reinforce Singapore.

¹¹ Some of these experiments led to the IMA "Swallow" smoke-screen-laying rocket-launched glider. Details of which can be found in Chapter 4 of "Sitting Ducks and Peeping Toms - Targets, Drones and UAVs in British service since 1917" by Michael L Draper. An Air Britain publication, ISBN 978-0-85130-407-6. The "Toraplane " stand-off torpedo delivery system did see limited production and Beaufort aircraft of both 22 and 43 Squadron RAF were equipped to use it and carried out trials that included "formation drops", but the accuracy achieved was not very good, so it was never used in action. See "The Gliding Bomb" article in the "Out of the Archives" feature in the Winter 2004 (issue 120) of Air Britain's Aeromilitaria magazine for details. The book "The Last Torpedo Flyers" By Arthur Aldridge (published by Simon & Schuster) includes details of taking part in trial drops of the Toraplane.

Sources

Air Ministry Publication AP1524A Vol 1 "The Wellesley I Aeroplane". The official maintenance guide to the Wellesley.

Vickers Wellesley by Ian White in the Warpaint series (number 86) from Warpaint Books (Guideline Publications).

Vickers Wellesley Variants by Norman Barfield, Aircraft Profile publication number 256 (Sept 1973).

Winged Crusaders - The Exploits of 14 Squadron RFC & RAF 1915-1945 by Michael Napier, published by Pen and Sword ISBN 978 1 78159 059 1.

Harrassing the Italians out of East Africa - 47 Squadron Operations. An article by Martyn Chorlton in the November 2014 edition of Aeroplane magazine.

Long Ranging Through - LRDU Wellesleys to Australia an article by Colin A Owers in the May-June 1996 edition (no 63) of Air Enthusiast Quarterly magazine.

Vickers Aircraft since 1908 by CF Andrews and EB Morgan, published by Putnam, ISBN 0 85177 815 1.

The British Aircraft Specification File by KJ Meekoms and EB Morgan (An Air Britain Publication) ISBN 0 85130 220 3.

Wellesleys an article in the 1986, issue 3 edition of Air Britain Aeromilitaria magazine.

Not Peace but a Sword by Wg Cmdr Patrick Gibbs, ISBN 0-948817-68-2, mentions the use of the Wellesley for torpedo dropping trials.

Erk's Progress- Part 4 - An article by Fred Adkins in the April 1979 edition of Aeroplane Monthly magazine gives an insight into what it was like to be groundcrew on a Wellesley Squadron. Fred was with 35 Squadron at Worthy Down when it converted from Fairey Gordons to Wellesleys and through until it re-equipped with Fairey Battles. Of particular note is the experience of working with more advanced hydraulic and electrical systems the Wellesley gave to a generation of groundcrew more used to older biplane designs.

Truculant Tribes, Turbulent Skies by Vic Flintham, published by Air Britain in 2015. ISBN 978-0-85130-468-7. It has details of the early pre-war deployments of Wellesleys to Palestine, Egypt, Sudan and Kenya.

A short letter from a Mr R.A.R. Wilson who flew as a naval observer with 47 Squadron Air Echelon, detailing its operations, appeared in the letters column of the December 1970 edition of Air Pictorial magazine.

My thanks to Christopher Amano-Langtree for pointing out the differencies in configuration of the early production aircraft and for providing details of the "drop-in" second pilot conversion. Also for providing details of No 7 Squadron's first use of the Wellesley, sharing details of the bomb-nacelles, pointing out that Vickers guns were used in early Wellesleys and providing details of the way the LRDU developed from 148 Squadron.