Dinger's Aviation Pages

The Hafner Rotachute, Rotabuggy and Rotatank

The British military had watched the development of parachute forces in first the Soviet Union and then in Germany with a certain amount of amusement, mistakenly thinking such forces could be easily picked off while still in the air or quickly surrounded by superior forces once on the ground. The success of the German Fallschirmjäger, first in Norway and then in Holland quickly forced a reappraisal. The British swiftly organised parachute troops of their own, largely copying the techniques they observed the Germans use. However, they were also keen to "leap-frog" the technology used by the Germans in any way they could. We are so familiar with seeing modern parachutists descend with accuracy onto tiny targets that it is easy to forget that in the Second World War the parachutes of the time did not allow much control at all. Paratroops had to largely trust to luck as to where they would land. German parachutes featured a single strap that the wearer dangled from and had no control at all, the British and American parachutes featured a much better shoulder harness that allowed a bit of control, but nothing like the control modern parachutes allow. There had been an attempt, by a Major Edward L Hoffman of the US Army Air Corp, to design a triangular parachute that allowed a greater degree of steering and a number were purchased by the US Army Air Corp starting in 1932. However, they had a number of issues, not least of which was the greater expense of manufacture, their procurement was stopped in 1936.

Enter Raoul Hafner an Austrian autogyro pioneer who had settled in Britain to develop and sell his AR III Gyroplane. In 1938, in response to Air Ministry specification S22/38 he had submitted designs for a two autogyros (the AR V and a sub-scale development prototype the AR IV) to be used by the Royal Navy (there was a follow-on helicopter design). The design was accepted and construction had started (by Short Bros) when in May 1940 Hafner was interned as an "enemy alien". He was quickly released and became a naturalised British subject. For some reason, he did not proceed with the navy autogyro project when released. Instead, his work switched to the problem of producing a more controllable alternative to the parachute. He thought he could use the autorotation principle of the autogyro to produce an unpowered rotor alternative to the parachute that would allow much greater control and accuracy. It had obvious applications for dropping spies and saboteurs behind enemy lines and also for coup de main operations to seize or destroy objectives in enemy territory. He presented his ideas in September 1940 and they were enthusiastically taken up. Hafner set up a team at the Airborne Forces Experimental Establishment (AFEE) based at Ringway (now Manchester Airport). In June 1942, AFEE would relocate to Sherburn-in-Elmet near Leeds and then move to Beaulieu in Hampshire in January 1945.

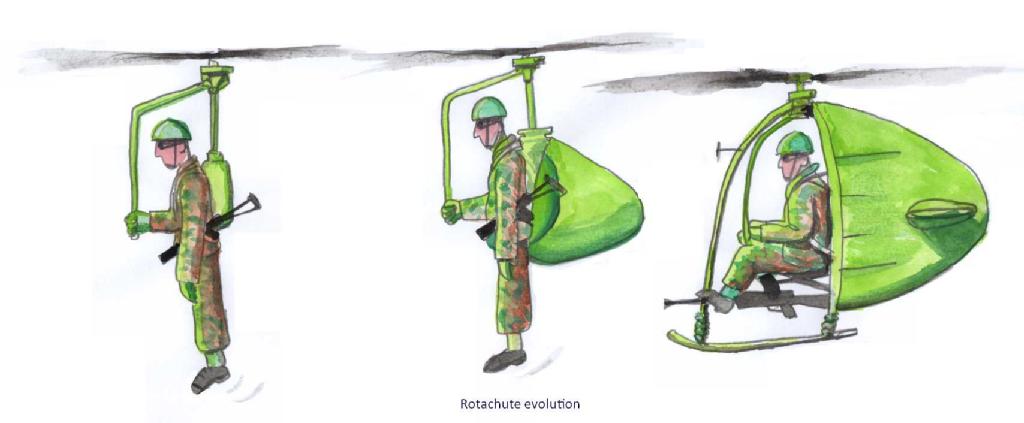

The development of the early Rotachute. On the left is the device as originally conceived, worn on the back like a parachute with folding rotor-blades that would spring open when the wearer jumped from an aircraft. Static tests showed a lack of directional stability which led to the middle development which featured an inflatable fin blown up once in flight by compressed air (like a life jacket) and kept rigid by air captured in side-pockets. More tests showed this still did not have enough directional stability so further development led to the Mk I Rotachute on the right which used a metal framework to hold the pilot. The tail was still a bag of rubberised fabric held rigid by the airflow into it. The Mk I was the first Rotachute to take to the air with a pilot, albeit only towed behind vehicles. It proved that even more stability was needed. Note that the Mk I featured the ability to mount a Bren gun under the pilot. It was envisaged this could be fired via a cable to give covering fire during the final stage of landing and then be disconnected to be used once on the ground.

That led via the Mk II and Mk III to the MK IV and Mk V, the ultimate Rotachute. This had a rigid fin and small endplates on the tail to give the required stability.

That is how the origins of the project are usually presented, however, it is possible that it was in response to intelligence that the Germans were working on "backpack helicopters". Hafner might have known his former Austrian associate, Bruno Nagler, was working on a small "backpack" helicopter for the Germans, and that another Austrian engineer, Paul Baumgärtl, was also engaged in similar work. Also, during the summer of 1940, the German, English-language propaganda radio station NBBS put out stories of "hovering" parachutes able to land spies and saboteurs; these stories were backed up by actual drops of spurious sabotage equipment into Britain by the Luftwaffe¹. So Hafner's Rota project may well have started off to investigate if such a thing was possible and try to anticipate future German developments.

The Baumgärtl Heliofly III wearable helicopter was developed by the Austrian Paul Baumgärtl. Another Austrian, Hafner's former colleague, Bruno Nagler was also working on a similar project. Was Hafner trying to duplicate their work?

Manufacture of the initial prototypes was carried out by F Hills and Sons. Tests at Ringway, involving rotors with dummy loads towed behind vehicles or dropped from aircraft, soon showed that the initial hopes of a simple foldable rotor worn like a parachute were impractical. It soon became apparent that a fin of some sort was needed to give the desired directional stability. At first, it was hoped that a small "blow-up" one would suffice, but further testing proved it needed to be larger and to support the fin a metal framework was needed that the wearer would sit in. Time dragged on and the first towed test of a Rotachute with a pilot on-board (the Mk I piloted by Sqdn Ldr I. M. Little towed behind a Humber car) did not take place until 11th February 1942. The Mk I led to the Mk II which featured an even larger fin (albeit still essentially a rubberised bag kept inflated by air flowing into it). This, in turn, led to the Mk III with an even larger fin, this time manufactured as a self-supporting structure complete with small tailplane. The Rotachute had grown from the initial idea of a small strap-on parachute alternative, worn by the "wearer" into a substantial gyroglider flown by a pilot.

The Hafner Rotachute Mk IV

Testing of the numerous prototypes continued (Hafner said that a total of twenty rotachutes of various marks were built), progressing from towing behind cars and trucks to being towed behind Tiger Moth aircraft (in one case for 40 minutes). Squadron Leader Little was joined in the testing programme by Robert Kronfeld the renowned glider pioneer. At the end of 1942, the project was retrospectively allocated Air Ministry Specification 11/42. The fitting of endplates to the tailplane of the Mk III in May 1943 finally produced a craft that performed well in all respects, although further refinements led to the Mk IV and V versions. Five examples of the Mk V being built. However, the problems of actually delivering the Rotachutes to the target area for the assault role had not been addressed. Also the growth in the structure of the Rotachute had made it unattractive for delivering spies and saboteurs (it is one thing to quickly bury or hide a parachute after landing, quite another to dispose of the tiny aircraft the Rotachute had grown into). In the meantime, the British had already used gliders carrying troops to seize bridges during the invasion of Sicily and there seemed little point in carrying on with Rotachute development. Various spin-offs were explored; an unmanned Rotachute style device was suggested as an alternative to parachutes for delivering air-dropped sea-mines and supplies and an unmanned Rotachute towed behind a ship as an alternative to a barrage balloon was another. Paradoxically, the use of the Rotachute as a towed "crows nest" was never explored, something the Germans developed the Focke-Achgelis Fa 330 rotary kite for. This was a role the Rotachute would have been well suited for.

It may well be that the failure to produce a workable way to deliver the Rotachute simply served to show that the Germans had little chance of getting the concept to work either. Neither Bruno Nagler or Paul Baumgärtl managed to produce a workable wearable helicopter or rotachute.

The Rotachute was sidelined for the later Rotabuggy project (see below). However, some of the Rotachute prototypes was shipped to the USA for testing. The Americans were very impressed with the results and looked into adapting the technology for their own use. A couple of "gyro gliders" flying in the USA shortly after the war appear to be close copies of the Rotachute. The Bensen Gyroglider seems to have been directly inspired by them. The one in <this YouTube video> looks to be identical in overall configuration, while the one < in this video> seems to have the control elements from the Rotachute mated to an airframe copied from the Focke-Achgelis Fa330. A decade later the American Kaman helicopter company was still looking into the use of the Rotachute principal for dropping supplies by air.

It may well be that the failure to produce a workable way to deliver the Rotachute simply served to show that the Germans had little chance of getting the concept to work either. Neither Bruno Nagler or Paul Baumgärtl managed to produce a workable wearable helicopter or rotachute.

The Rotachute was sidelined for the later Rotabuggy project (see below). However, some of the Rotachute prototypes was shipped to the USA for testing. The Americans were very impressed with the results and looked into adapting the technology for their own use. A couple of "gyro gliders" flying in the USA shortly after the war appear to be close copies of the Rotachute. The Bensen Gyroglider seems to have been directly inspired by them. The one in <this YouTube video> looks to be identical in overall configuration, while the one < in this video> seems to have the control elements from the Rotachute mated to an airframe copied from the Focke-Achgelis Fa330. A decade later the American Kaman helicopter company was still looking into the use of the Rotachute principal for dropping supplies by air.

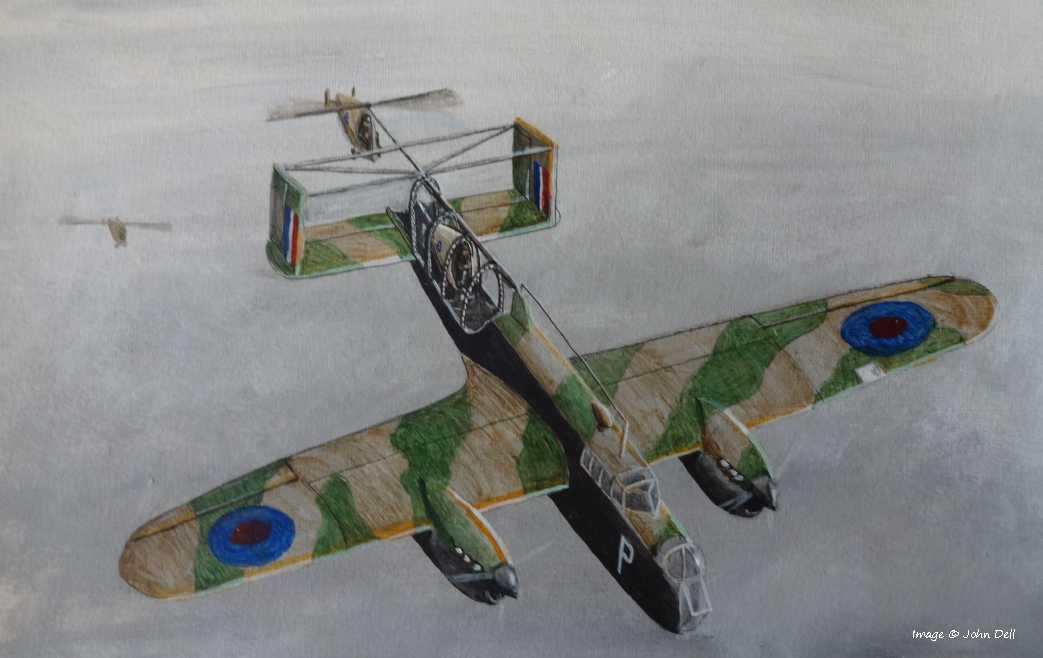

How the Rotachute might have been used in service.

The evolved Rotachute would need to be towed all the way to the target (extremely slowly and with great discomfort to the pilot) but it was suggested that aircraft could be modified to carry some Rotachutes suspended from a bar. The Rotachutes would then be run out in turn to the end of the bar to allow the rotors to spin up before being dropped. The painting above imagines an A.W. Whitley modified for this purpose.

Free from the Whitley the Rotachutes are guided towards their target.

In this case a river crossing, the classic target for such a pinpoint coup de main assault.

The Rotabuggy

In August of 1940, interrogation of captured German prisoners revealed the possibility that the Germans were planning to use "flying tanks" for the invasion of Britain. Prisoners claimed to have seen light tanks fitted with detachable wings² (seemingly something akin to the Russian Antonov A-40). It is possible that this intelligence was relayed to Hafner and prompted his work to see if the "Rota" principle could be expanded to the delivery of vehicles. At the same time, the growth in the structure of his rotachute project, from the initial idea of a simple alternative to a parachute into a miniature aircraft with rotary wings, must have surely prompted Hafner to consider a larger design to take more passengers. A similar thought process saw the Germans experimenting with the Focke-Achgelis Fa 225 rotary wing glider.

The Focke-Achgelis Fa225 was the standard German 9-passenger DFS 230 assault glider fitted with an unpowered rotary wing. Only one was built and tested.

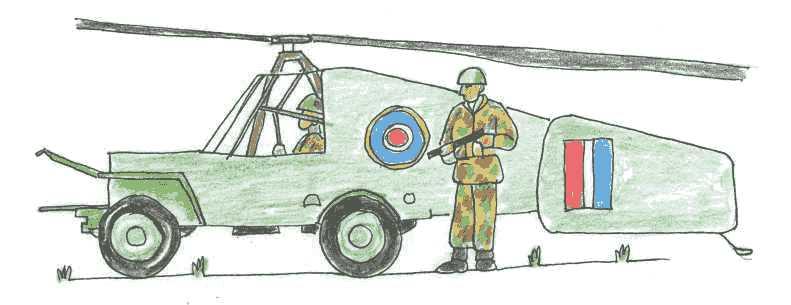

British Horsa gliders were capable of carrying Jeeps but it occurred to Hafner that the Jeep itself already had a set of wheels to act as an undercarriage and if the Jeep could be mated with a rotor and tail it would provide a mini rotor-glider that could be landed with much greater accuracy and into much more confined spaces than conventional gliders. It would also be much cheaper than a conventional glider (it was calculated that seven such Jeeps could be converted for the cost of one Horsa Glider). A quick test of a Jeep (simply by dropping it from increasing heights) showed that the basic suspension and structure was more than adequate for the role. So in April 1942 was born the "Rotabuggy" project. It was given Air Ministry Specification number 10/42 with production of the prototype contracted to R. Malcolm & Co to be built at their White Waltham facility.

The Rotabuggy under construction.

With the lessons learnt from the Rotachute, initial construction of the prototype proceeded very quickly. It featured an extended windscreen and a large tail with tailplane and endplates. The tail and overhead rotor could be quickly detached. The Rotabuggy was flown from the front "passenger" seat with the controls hanging into the Jeep from the overhead rotor. Some descriptions of the Rotabuggy mistakenly imply that it would only have flown with the one pilot on-board. However, the Rotabuggy needed someone in both the "pilot" and "driver" position. The "driver" used the conventional steering wheel to steer until the craft was airborne when the pilot took over. The prototype was ready to start towed tests behind a lorry in November 1943 but the lorry was not powerful enough to get it into the air. A Bentley racing car had to be used to get it airborne, and then only for short hops. Problems with vibrations plagued the prototype and then a heavy landing damaged the rotor blades and the project was delayed while a new set was manufactured. From the 24th of June 1944, a Whitley bomber was used to tow it around the airfield for longer hops (the Whitley itself stayed on the ground for these tests). It was not until September 11th 1944 that a first towed flight was attempted (towed by a Whitley) with Sqdn Leader Little as the pilot and Flt Lt Packman (an engineering officer) sitting alongside in the Jeep's driver position. The flight was a near disaster, severe vibration occurred at the increased airspeed and the Rotabuggy proved to be very tail-heavy in the air under tow and there was no way to trim this out. After a very fraught flight with the Whitley reducing speed to just above stalling the combination managed to land safely. This was the Rotabuggy's first and last proper flight towed behind a flying aircraft. With D-Day past and the collapse of Germany imminent and with a stockpile of Horsa gliders already built there seemed little point in carrying on with the Rotabuggy project. The prototype had its tail and rotor removed and was used by the Airborne Forces Experimental Establishment's motor pool at Beaulieu. Ironically, one of the tasks it carried out was towed tests of a captured German Focke-Achgellis FA330 rotakite. The original Rotabuggy was eventually scrapped, the one at the Museum of Army Flying at Middle Wallop being a replica.

The Rotabuggy prototype during trials at Sherburn-in-Elmet, near Leeds, home of the Airborne Forces Experimental Establishment (AFEE). In the background, you can see a Horsa glider. The Horsa could carry two Jeeps without passengers or one Jeep with passengers and a load of ammunition.

Side view of the Hafner Rotabuggy

The Hafner Rotabuggy painted as if it had gone into production and service, towed by Bristol Albemarle aircraft.

In many online descriptions of the Rotabuggy, it is asserted that it was specifically nicknamed the "Blitz Buggy". This is not true. The misunderstanding results from a misreading of Philip Jarrett's "Nothing Ventured" article in the October 1991 edition of Aeroplane monthly magazine. "Blitz Buggy" was a nickname given to all "Jeeps" when they were first introduced. The term was first used in American G.I. slang at the start of the 1940s to refer to any military vehicle. It later became attached specifically to the Willys 1⁄4 ton 4x4 small truck when it was first introduced in large numbers. This nickname was itself replaced by the term "Jeep".

Link to contemporary magazine article (Popular Mechanics Nov 1942) that refers to Blitz Buggies.

Link to Youtube video of US Training film "Crack that Tank" - 1 minute 20 seconds in hear reference to Blitz Buggies.

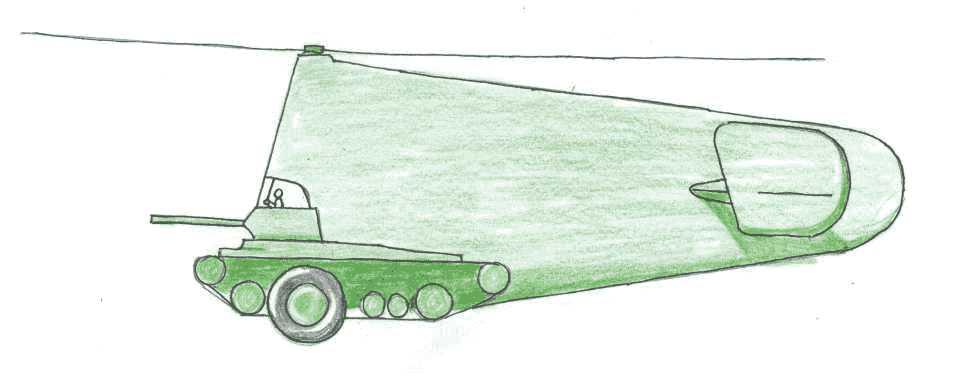

The Rotatank

Hafner's last thought on the "Rota" concept was the "Rotatank". He outlined this proposal in a report dated the 18th December 1942, well before his Rotabuggy prototype had even started trials. This mated a heavy tank (a Vickers Valentine) with a huge tail and rotor. The pilot would sit in the commander's hatch in the turret controlling the craft in the air via controls descending from the rotor. A pair of huge wheels on a "dolly" would be used on take-off and then be dropped, the tank landing on its tracks. The scale of the project was daunting. The rotor required would have been over 150 feet ( 46 metres) in diameter and the blades were each over 6 feet (2 metres) wide. Hafner calculated that no existing single aircraft in RAF service could tow such a design and he suggested that a Halifax 4 engined bomber would tow the Rotatank but would, in turn, need itself to be towed by a DC3 Dakota to get airborne. Hafner never seems to have followed up on his Rotatank proposal (the last paragraph of his 1942 report implied that the Rotatank project should only be undertaken if the Rotabuggy was a success). By the end of the war, the Valentine was an out-moded tank and had been replaced by even heavier designs. So it is no surprise that the scheme was never followed up.

Side view of a Rotatank complete with the launch dolly with huge wheels. This would have been dropped after take-off. The tank would land on its tracked running gear. Clutch out of course!

Hafner Rotatank based on a Valentine Mk X tank.

Afterwards and afterthoughts.

Raoul Hafner went on to head the helicopter division of the Bristol Aeroplane Company, designing the Type 171 Sycamore and Type 192 Belvedere helicopters. When Bristol's helicopter division merged with Westland helicopters in 1961 Hafner became Technical Director, a post he held until retirement in 1970. He was killed in a sailing accident in 1980.

A certain amount of criticism is levelled at the various "Rota" projects, characterising them as laughable, wacky, hair-brained, "Heath Robinson" contraptions. The fact that none of them ever got into service is usually cited as proof they were unviable. However, a case can be made that the Rotas were all constructed and investigated in response to intelligence that the Germans were developing the same sort of designs. If this alternative view is taken then the various Rota projects can be seen as a prudent use of scarce resources to find out the potential and limitations of such rotorcraft.

With hindsight, it is clear the best use of Raoul Hafner's genius and drive would have been to ask him to carry on with his navy autogyro AR IV and AR V project along with his follow-on PD6 and PD7 helicopter designs. Better still if he could have combined his work with that of the G & J Weir company who had the first proper British helicopter (The Weir W-5) flying as early as 1938 and were working on the revolutionary W-9 from 1943.

A certain amount of criticism is levelled at the various "Rota" projects, characterising them as laughable, wacky, hair-brained, "Heath Robinson" contraptions. The fact that none of them ever got into service is usually cited as proof they were unviable. However, a case can be made that the Rotas were all constructed and investigated in response to intelligence that the Germans were developing the same sort of designs. If this alternative view is taken then the various Rota projects can be seen as a prudent use of scarce resources to find out the potential and limitations of such rotorcraft.

With hindsight, it is clear the best use of Raoul Hafner's genius and drive would have been to ask him to carry on with his navy autogyro AR IV and AR V project along with his follow-on PD6 and PD7 helicopter designs. Better still if he could have combined his work with that of the G & J Weir company who had the first proper British helicopter (The Weir W-5) flying as early as 1938 and were working on the revolutionary W-9 from 1943.

Notes

¹ Details of the Nazi "black" radio stations giving out what today would be called "fake news" and the stories they told of spies and saboteurs being parachuted into Britain, can be found in a chapter in Peter Fleming's book "Invasion 1940", published by Rupert Hart-Davis in 1957. The story of the German deception plans for "Operation Sealion" seems to have been largely neglected in the past few decades, strange in view of the many books, articles and documentaries devoted to the Allied deception plans for D-Day. Fleming's book is a good primer for anyone who wants to look into this further; it is usually possible to pick it up at a very low cost on ebay.

² British intelligence of German "Flying Tank" designs is mentioned in "Luftwaffe, The Allied Intelligence Files" by Christopher Staerck and Paul Sinnot, Published by Brassey's in 2002. ISBN 1-57488-387-9. It is under the section devoted to the Junkers Ju 52.

Links

Hafner's earlier autogyro and helicopter projects

Video of Hafner and Nagler R2 Revoplan of 1932

Video of the Hafner AR III Gyroplane of 1935

Rotabuggy article on the Aviastar website.

Notes on Sources

The two articles in the "Nothing Ventured" series by Philip Jarrett in the August and September 1991 editions of Aeroplane Monthly magazine are highly recommended. The August Edition covers the Rotachute and the September edition the Rotabuggy and Rotatank. Also, note that the October edition has a letter in the "Skywriters" column by Ted Vaisey who worked on the Rotachute with comments on the earlier article.

A few paragraphs alongside a very good diagram of the Rotabuggy appear in the Winter 2006 edition of Air-Britains "Aeromiltaria" magazine.

The Hafner Rotabuggy features in an article in the March 2012 edition of "Britain at War" magazine and a letter from Alistair Mellor in the May edition gives some details of the Rotatank design and a photo showing that the Jeep section of the prototype Rotabuggy was used to tow a captured Focke-Achgellis FA330 rotakite for trials.

"British Rotorcraft": an article by Raoul Hafner in the Centenary Journal of the Royal Aeronautical Society (number 661, Volume 70, January 1966).

"The British Aircraft Specification File": by KJ Meekcoms and EB Morgan, published by Air Britain, ISBN 0 85130 220 3.

Hafner's declassified report on his idea for the "Rotatank", dated 18/12/42, AFEE ref S.4801/5/Tech.

An overview of parachute developments prior to and during WW2, including the Hoffman parachute, can be found in the article "Development of Parachutes to 1945" , edited by R Ray Ortensie. Available at <this link>.