Dinger's Aviation Pages

The Twin-Engined Developments of the Fairey Battle Bomber.

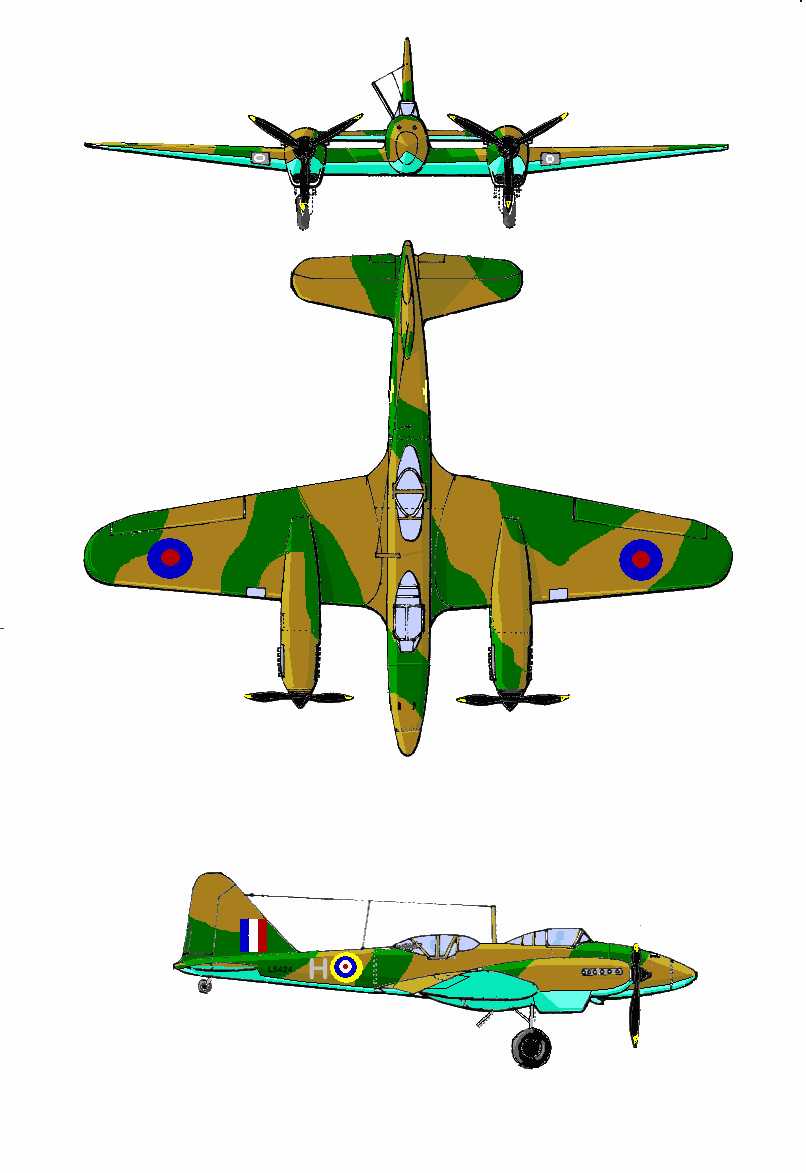

Not so much a development, more a parallel project, the twin-engined "Battle" is an intriguing "might-have-been". This is the original design with separate canopies for the pilot and rear gunner. Based on original Fairey layout drawing.

In the aftermath of World War One, a series of disarmament talks resulted in the Washington Naval Treaty that restricted the number and size of large warships for the major world powers. It was hoped that the World Disarmament Conference, that started in Geneva in 1932, would lead to a similar treaty that would limit the number and size of bomber aircraft. The British Air Ministry was already sponsoring the development of large multi-engined bombers (via specification B9/32 resulting in the Wellington and Hampden), but it was thought prudent to order a new design to fit within the likely limits of the proposed treaty; so that the RAF would still have a bomber force if the larger bombers were banned. The Air Ministry wrote an Operation Requirement (OR7) for the new design and then issued Specification P27/32 for the new aircraft (this was in 1932, before Hitler came to power in Germany). Seven companies submitted tenders (Armstrong-Whitworth, Bristol, Fairey, Gloster, Hawker, Vickers and Westland) from which the Air Ministry selected the Fairey and Armstrong Whitworth designs and agreed to finance the building of prototypes (the early version of the Vickers Type 246 design tendered would eventually emerge as the Wellesley bomber to a later specification only after Vickers had financed the building of a prototype themselves).

Battle prototype K4303 in flight. Notice the wheel protruding below the wing into which it only partly retracted. The Battle's streamlined form can deceive observers as to its size. It was a surprisingly large aircraft, being 2 foot 6 inches (76 cm) longer than a Blenheim Mk I twin-engined bomber and only 3 inches (7.6 cm) shorter than the "long-nosed" Blenheim Mk IV.

This specification was for a bomber aircraft to equip the main strategic striking force of the RAF (known as Bomber Command after 1936). Targets for the new design would be the industrial heartland of an enemy or railway or port communication nodes. To meet the likely weight limits of the expected disarmament treaty the aircraft had to weigh less than 6.300 Ib (2, 858 kg) unloaded, and have a single engine. A bombload of 1,000 lb (454 Kg), one fixed forward machine gun and one flexible mounted rear machine gun were also specified, as was a maximum speed of 195 mph (313 kph) and ceiling of at least 22,000 feet (6,096 metres). Originally, a two-man crew was specified, but this was later increased to three and other aspects P27/32 were "tweaked" by the Air Ministry to the exasperation of Fairey and Armstrong-Whitworth.

The Armstrong-Whitworth AW29 was the other prototype ordered to meet P27/32. Its "cabin" arrangement with a rotating turret to the rear, (not visible in this photo) was probably closer to what the Air Ministry expected from a specification to essentially do the same job as the Wellington bomber with a smaller bombload, in a smaller airframe. Notice the rearward retracting wheels, which would have looked more at home in a twin-engined configuration.

Richard Fairey, head of the Fairey Aircraft Company, was quite convinced that the needs of P27/32 would be better met by a twin-engined, rather than single-engined, design. However, the Geneva disarmament conference still held out the hope of a limitation on the weight of bombers (the conference broke up in 1934 but the possibility of restarting it or having a separate treaty with Germany only finally disappeared in 1937) and so the Air Ministry insisted on the original brief for a lightweight, single-engined aircraft. However, right from the start of the design process, Fairey had the new aircraft designed in such a way that it could be readily modified into a twin-engined machine. The cockpit, middle and rear fuselage assemblies, outer wings and undercarriage would be common to both designs, while the twin-engined variant would have a new nose holding forward-firing armament. In this way, production could be easily changed to the more capable twin-engined design if the disarmament talks broke down. The way the undercarriage of the Fairey Battle works, retracting back into the wing, in a way that could be easily accommodated in the engine nacelles of a twin-engined type, clearly shows the philosophy at work. It may be that across at Armstrong Whitworth the same thought process was going on, their AW29 design to the same specification, had a very similar undercarriage arrangement.

Image of a Fairey Battle manipulated to show the layout of the twin-engined variant.

Fairey had hoped to use its own 12 cylinder inline liquid-cooled "Prince" engine on the Battle. This was similar to the Merlin engine but somewhat smaller and consequently less powerful. As originally designed the Battle was to have had separate canopies for the pilot and the rear gunner (like the layout of the Vickers Wellesley). The twin-engined variant shared both these original features but changed when they were dropped from the single-engined design (Fairey could not get Air Ministry support for the Prince engine and wind-tunnel tests showed a long single-canopy, spanning both pilot and gunner positions, created less drag). The Rolls-Royce Merlin engine was used instead (the Battle was the first production aircraft fitted with the Merlin and development problems with the new engine led to a delay in getting it into service).

At first, the Air Ministry was wary of ordering any of the single-engined Battles. It would have rather waited for the availability of the much larger twin-engined Whitley, Wellington and Hampden. But Fairey did an outstanding job in developing the Battle, they learnt a lot from their experience with the outdated design of their Hendon bomber and used the latest techniques in metal stressed-skin design from the USA to produce an aircraft that handsomely exceeded the requirements for top speed and range. The revelation of the pace of German rearmament forced the Air Ministry to adopt emergency measures to try to catch up and achieve parity with the Luftwaffe. The easily produced and cheap Fairey Battle was seen as the ideal aircraft to swiftly increase the RAF's front-line strength. The Battle's small bombload was not seen as an issue; if they were based in France they could hopefully fly two or maybe even three, sorties in a day, and their top speed of some 257 mph (414 kph) and cruising speed of 200 mph (321 kph) should mean there was little chance of interception by the Luftwaffe's Heinkel He 51 and Arado Ar 68 biplane fighters which had top speeds of around 210 mph (338 kph)

The Battle was ordered into quantity production, the first order for 155 aircraft was quickly followed by another for 500 from Fairey and 400 from a shadow factory operated by Austin in Birmingham and follow-on orders kept coming until, in total, 2,201 Battles were built. This production was largely a political expedient. The RAF had identified remarkably early that the advent of monoplane fighters with engines in the same class as the Merlin would render the Battle obsolete. Even before the first Battles entered service, Sir Edward Ellington, the Chief of the Air Staff, was calling for orders to be cut back and the following year Sir Wilfred Freeman, in charge of RAF research and development, was calling the Battle a "mistaken concept". But before war was declared it was thought that large numbers of Battle squadrons would have a better deterrent effect than a reduced number of some larger multi-engined type. There was also a hope that the bulk of the German fighter strength would still be made up of older biplanes. It was a considerable shock to discover that the Germans had completely replaced biplanes fighters with the Bf109 and that even the less potent early Bf109 model B, C and Ds had been superseded, in the front line, by the latest Bf109E.

Fairey kept up the fight to try to get the twin-engined variant into production. The Fairy archivist, ID Huntley, suggested that the very name "Battle", suggested by Richard Fairey and adopted by the Air Ministry in April 1936 was an "in-joke" meant to symbolise Fairey's battle to get the twin-engined version adopted. Such an aircraft would have seen a huge leap in the level of performance; with twin Merlin engines it is hard to see it having a top speed below 300 mph and probably a lot more. With the possibility of a heavy armament of machine-guns, and later cannons, in the nose, it would have been a formidable fighter-bomber and night fighter, on a par with the Bristol Beaufighter and approaching the Messerschmitt Bf110 for flexibility. It would not have had the aerodynamic refinement to match the DH Mosquito for performance (the thick wing to accommodate bomb-cells would have precluded that). But it would have been a very welcome addition to the RAFs armoury in 1939 through to 1943.

The Merlin engine was much in demand. It powered the Hurricane and Spitfire fighters, the Whitley night-bomber, and was also required for the upcoming Fulmar carrier fighter. If the twin-engined Battle had replaced the single-engined version in production and service it would have need to be produced at half the rate. Otherwise, they would have had to cut the production of other aircraft types to match Merlin production.

What an early-war twin-engined Fairey Battle might have looked like.

Production of the twin-engined variant would have proved a problem at the Austin shadow factory. Its airfield was a small area on top of a hill and completed Battles had to be hauled up from the "flight shed" on a "ski-lift" arrangement. The fight shed, ski-lift and tiny airfield could not have accommodated a twin-engined aircraft, so partially completed airframes would probably have to be taken across the city of Birmingham for final assembly at Elmdon aerodrome (now Birmingham airport). That was the procedure adopted when Austin switched to producing Stirling bombers at the end of 1940. As it was, production of the single-engined Battle continued throughout the Battle-of-Britain period and the vast majority of Battles produced never saw combat service but were used as trainers and target-tugs instead.

When war was declared, all ten Battle squadrons of 1 Group Bomber Command were sent to France to form the "Advanced Air Striking Force" (AASF) based at aerodromes around Reims. These aerodromes were remote from the British Army forces that formed the British Expeditionary Force (BEF), who had a completely different formation of the RAF to support them: the British Expeditionary Force Air Component (BEFAC) which had a mixture of Hurricanes, Lysanders and Blenheims (the latter used primarily for reconnaissance). The Battles were there to strike at German industry in the Rhur and their crews were not trained for cooperation with the Army or the types of tactical targets it was called upon to attack in the German Blitzkrieg of 1940. To suggest that a twin-engined Battle could have reversed the defeat of 1940 is wishful thinking. The RAF had to learn the whole concept of the tactical use of air-power again, and it did this painfully during the Desert War in North Africa. If you had given the RAF Mosquitos and Typhoons in 1940 they would still have not stopped the Germans onslaught, although more crews might have survived to fight again (I cover this subject at length in my article on the Hawker Henley).

The traditional twin-engined Battle was never produced, not even in prototype form. But a twin-engined Battle did fly, and very successfully at that. Fairey had been trying to break into the production of aircraft-engines, a field dominated in the UK by Rolls-Royce, Bristol, Armstrong-Siddeley and Napiers. The Air Ministry thought that there were already too many aero-engine manufacturers and did not encourage Fairey in these aspirations (they also did not encourage the Alvis and Wolseley companies who were also trying to produce aero-engines in this period). The Fairey 720 horsepower 12 cylinder Prince I engine was the preferred engine for powering the Battle as originally designed, and if the Air Ministry had adopted the twin-engined variant at the very beginning, no doubt it would have been powered by two Prince engines. The Prince I was developed into the Prince 3 which developed a very impressive 1,540 horsepower and which was test-flown in a Fairey Battle, but the Prince 3 was not a single engine but in effect two Prince I engines, cut down from 12 to 8 cylinders, one above the other, in a single package (with a total of 16 cylinders) with no major mechanical linkage between the two. Each engine drove its own propeller, mounted together in a contra-rotating arrangement. This meant one "half" of the engine package could be powered down for economical cruising. Fairey took the Prince 3 and expanded it back to the original 12 cylinder layout of the original Prince engine doubled up to make a massive 24 cylinder unit giving 2,240 horsepower (hoped to be developed to 3,000 horsepower) called the P-24 Monarch.

The traditional twin-engined Battle was never produced, not even in prototype form. But a twin-engined Battle did fly, and very successfully at that. Fairey had been trying to break into the production of aircraft-engines, a field dominated in the UK by Rolls-Royce, Bristol, Armstrong-Siddeley and Napiers. The Air Ministry thought that there were already too many aero-engine manufacturers and did not encourage Fairey in these aspirations (they also did not encourage the Alvis and Wolseley companies who were also trying to produce aero-engines in this period). The Fairey 720 horsepower 12 cylinder Prince I engine was the preferred engine for powering the Battle as originally designed, and if the Air Ministry had adopted the twin-engined variant at the very beginning, no doubt it would have been powered by two Prince engines. The Prince I was developed into the Prince 3 which developed a very impressive 1,540 horsepower and which was test-flown in a Fairey Battle, but the Prince 3 was not a single engine but in effect two Prince I engines, cut down from 12 to 8 cylinders, one above the other, in a single package (with a total of 16 cylinders) with no major mechanical linkage between the two. Each engine drove its own propeller, mounted together in a contra-rotating arrangement. This meant one "half" of the engine package could be powered down for economical cruising. Fairey took the Prince 3 and expanded it back to the original 12 cylinder layout of the original Prince engine doubled up to make a massive 24 cylinder unit giving 2,240 horsepower (hoped to be developed to 3,000 horsepower) called the P-24 Monarch.

The huge P-24 Monarch engine with its contra-rotating propellers. It was actually two engines in a single unit.

In late 1937 the Merlin engine had development snags with its initial ramp-head design and was not yet being produced in the quantities required. This prompted the Air Ministry (in early 1938) to ask Fairey to look into producing the Battle with the P24 engine, or the Napier Sabre instead. When the Merlin's development issues were solved and more production came on-line this request was withdrawn.

Both the 16 cylinder Prince 3 and 24 cylinder Monarch were test flown in a Battle (K9370). It was the Monarch engine that was used most. Tests were very successful, the only issue being a high consumption of oil. In an article, the Fairey archivist ID Huntley, stated that the expected top speed of the P24 engined Battle was 365mph (587 kph). He also quotes a report that the P24 Battle was "...flown in competition with several contemporary fighter aircraft and could easily evade and out-manoeuvre them. Bearing in mind the present rating limit on the P24 engine, the Battle cannot be caught on an equal basis by fighters during initial climb and level flight manoeuvres. Turns in either direction are easy and climbing turns opposed to the engine torque of pursing single-engined fighters was most effective. The turns could be kept within the fighter's circle and the Battle rear gunner was afforded an almost continuous field of fire without the fighter bringing its guns to bear once. To escape, the Battle pilot had only to increase the rate of climb to leave the fighter behind."

What a Battle powered by a P-24 Monarch engine might have looked like in combat. Note the huge ventral radiator.

The Air Ministry were still not impressed enough to finance the P24 Monarch engine. Fairey persisted with their efforts, but the realities of setting up a new production line for the Monarch engine in a Britain starved of raw materials and under regular German bombing attack were formidable. Fairey tried to get the Americans interested in producing and developing the engine. In 1941, Battle K9370 and its P-24 Monarch were shipped off to the USA. Most books and articles on the subject assert this was part of the effort to get the USA to produce the engine (it is often said the P-24 was considered as an alternative powerplant for the Republic P-47 Thunderbolt fighter). Since the war, a series of declassified documents¹ show that the Americans rejected the idea of any sort of production or development of the P-24 in the USA in August 1941, before the P-24 Battle was shipped over. They based their rejection on diagrams and reports of the engine provided by Fairey and an inspection of the engine done in England by a representative of the American Allison engine company. They thought the engine showed no advantage over American engines already in development and were suspicious of many of the design elements that did not conform to American practice. However, they were very interested in the contra-rotating propeller system, the Americans had nothing like it flying at the time, certainly not at the power and speed of the P-24 Battle. They strongly recommended getting hold of a P-24 Battle to further American research in this area and save them having to build their own test aircraft. It was for this reason they took delivery of the P-24 Battle in December 1941 and kept it until 1943. It is not at all clear if the British appreciated the real reason the Americans wanted the aircraft.

Battle K9370 in the USA. Note the early style of US insignia (the Battle was delivered just days before the USA entered the war after Pearl Harbour).

K9370 with both engine components running, somewhere in the USA.

The P-24 Monarch engine is a whole "might-have-been" subject on its own. The list of British aircraft that could have benefited from it is long. One can imagine it as a replacement for the Rolls-Royce Vulture for the Hawker Tornado, Avro Manchester, Vickers Warwick and Blackburn B20. The ability to shut down half the engine for long-range cruising and the extra security of twin engines would have been of huge benefit to the Fairey naval aircraft, the Fulmar, Barracuda and Firefly. It was only after the war that the Fairey Gannet gained the advantages of such an engine with its Double-Mamba engine.

The P24 engine from the Fairey Battle still exists (pictured above), preserved at the excellent Fleet Air Arm Museum at Yeovilton. Photograph courtesy of Matt Willis.

Notes

¹ The documents in question are all from the War Department Air Corps Materiel Division. EXP-M-57-503-428 dated 22nd August is a report on an evaluation of the engine from data supplied by Captain Forsythe of the Fairey company (the engine's chief designer) and reports from Mr Hazen of the Allison Engine Company. EXP-M-52-587-12 dated 21st August 1941 is a report on an appraisal of the contra-rotating propeller system. EXP-M-52-592-29 dated 27th August 1941 considers both of the earlier reports and recommends the rejection of the P-24 engine for further development or production but recommends an example of the engine and propeller system, mounted in a suitable aircraft, be obtained to aid research into contra-props.

Links

Sources

The Battle File: By Sidney Shail, published by Air-Britain, ISBN 0 85130 225 4.

Fairey Battle: By ID Huntley, published by SAM Publications (Aviation Guide Series), ISBN 0 9533465 9 5.

The Unloved Battle: Two articles by ID Huntley in the August and October 1974 editions of Aircraft Illustrated magazine.

Fairey Aircraft Since 1915: By HA Taylor, published by Putnam, ISBN 0 370 00065 x.