Dinger's Aviation Pages

Cunliffe-Owen OA-1 "Flying Wing"

One of the most striking-looking aircraft ever to fly, the Cunliffe-Owen OA-1's chances of success were stifled by the outbreak of WWII.

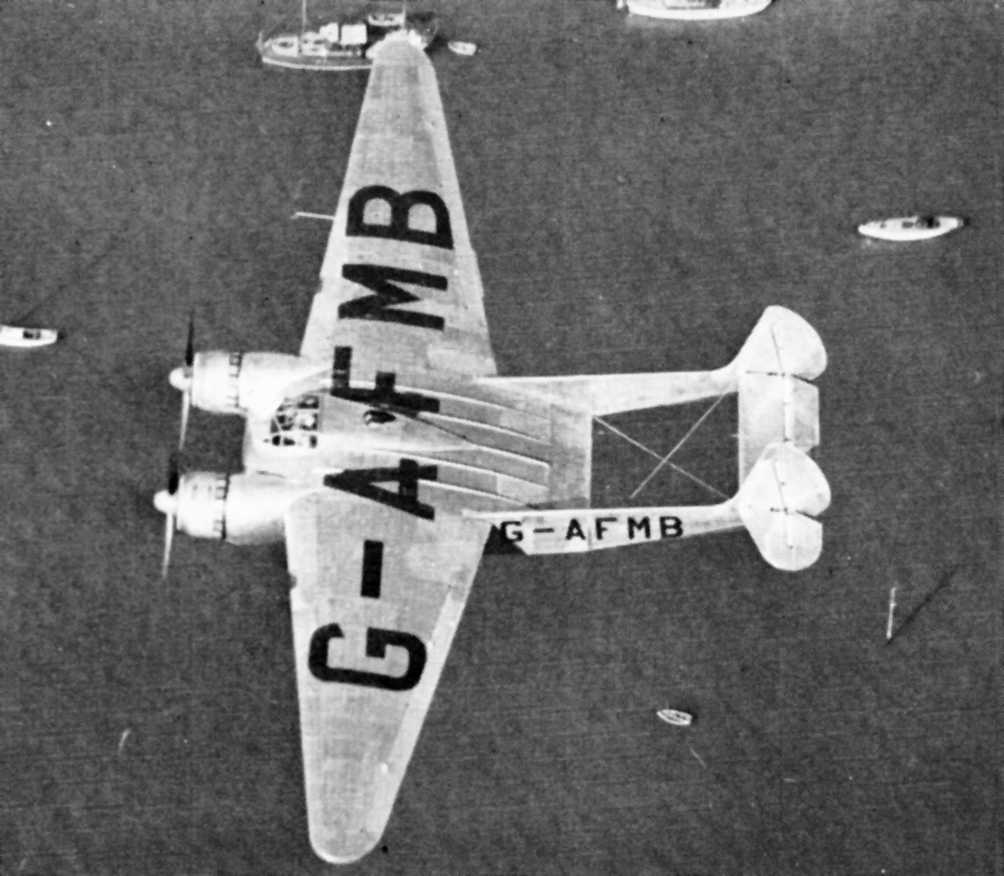

Having a tail, the Burnelli designs were not "Flying Wings" in the true aeronautical sense; the correct term would be "lifting fuselage". However, they were referred to as "Flying Wings" in contemporary newspaper and magazine articles, (even the British registration papers for G-AFMB give the aircraft type as "Flying Wing"). So, for simplicity, I will refer to them as such.

Having a tail, the Burnelli designs were not "Flying Wings" in the true aeronautical sense; the correct term would be "lifting fuselage". However, they were referred to as "Flying Wings" in contemporary newspaper and magazine articles, (even the British registration papers for G-AFMB give the aircraft type as "Flying Wing"). So, for simplicity, I will refer to them as such.

The only Cunliffe-Owen OA-1 built shown in flight over Southampton harbour. Designed to carry 15 - 20 passengers it was a compact design. It had retracting main and tail-wheels The cross-bracing of the tail-booms can be clearly seen. It is sometimes erroneously referred to as a "Clyde Clipper", a name for a previous Burnelli-inspired aircraft project undertaken by a different company, the Scottish Aircraft and Engineering Company.

During the late 1920s and 1930s, American aircraft designer Vincent Burnelli conceived and built a series of aircraft that sought to combine the attributes of a true "flying wing" with the practicalities of stability and size. These culminated in the UB-14 which first flew in 1934. A fuselage of wing profile provided a spacious and strong passenger cabin. A twin-boom tail provided the lateral stability impossible in true flying wing designs until the use of "fly-by-wire" technology. Closely grouped twin engines minimised asymmetric handling problems. The first prototype crashed in spectacular fashion at Newark Airport in New Jersey on the 13th January 1935, but the passenger cabin escaped with little damage, vindicating the designer's claims for the inherent safety of the design. A second prototype was soon flying (the UB-14B) and attracted worldwide interest.

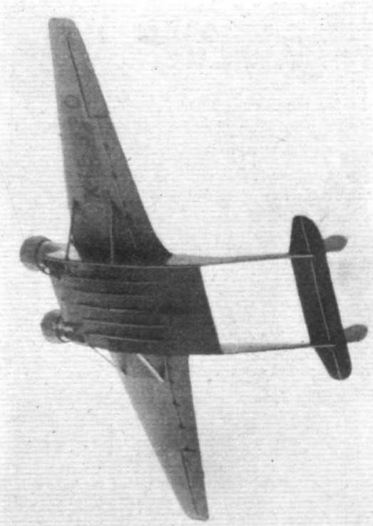

Spectacular shot of the Burnelli UB-14B (registration X-15320) over Manhattan. The UB-14B was slated for a transatlantic record flight, but in the event travelled to Europe as freight on a cargo ship and ended up impounded by customs in the UK before onward shipment to the Netherlands, where it was re-assembled and embarked on a European demonstration tour with the new registration NR15320, arriving back in the UK in December of 1937, after the Scottish Aircraft and Engineering Company that had been planning to build it under licence had been liquidated. It was shipped back to the USA, reportedly in preparation for a round-the-world record attempt but its licence was revoked in May 1939. It was then refurbished with subtle alterations to the rudders and had new engines fitted. It was sold to the Central American TACA airline in July 1943 and operated with the Nicaraguan registration AN-ABH. It was then used for freight-carrying flights over the Caribbean. Last reported as being unairworthy in December 1945, its ultimate fate appears to be unknown.

Photo of the Burnelli UB-14B. Compare it with the photo of the Cunliffe-Owen OA-1 at the top of the page; you'll see substantial changes. The OA-1 looks a lot larger. The cockpit is completely different and the tail booms of the UB-14B are much more slender than those of the OA-1.

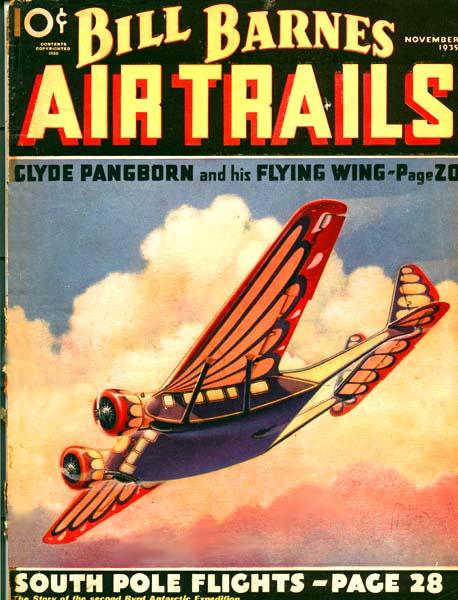

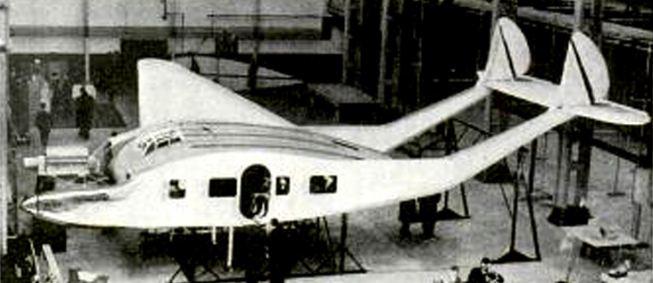

This cover of an American aviation magazine shows an approximation of the Burnelli UB-14 in a particularly exotic colour scheme. The article in the magazine covers Clyde Pangborn's involvement with the "Flying Wing". Clyde Pangborn was a pioneer U.S. aviator who gave considerable backing to Burnelli and who had planned to use the UB-14 on record-breaking flights. It seems his first name being the same as the "Clyde Clipper" was a happy coincidence. Pangborn went on to work for Cunliffe-Owen in the UK and was the test pilot for the first flight of the OA-1. Later he joined the RAF where he was instrumental in setting up the Atlantic Ferry organisation. A true hero; you can read about him in this Wikipedia article <click here>.

The Burnelli UB-14 in flight.

The Burnelli UB-14 in flight.

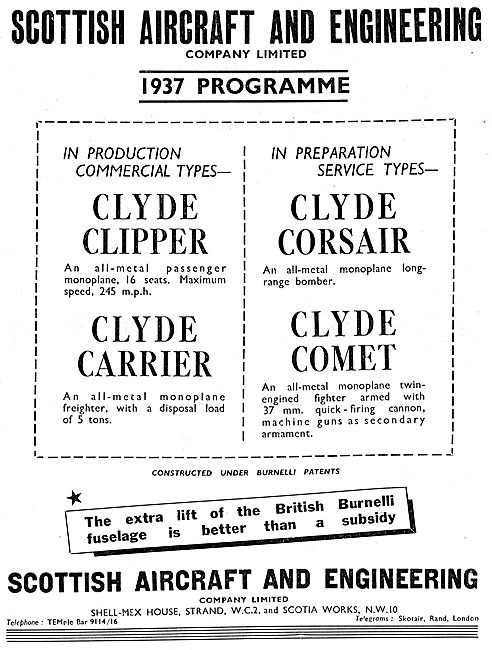

Burnelli never succeeded in getting his brainchild into production in the USA, (there is a conspiracy theory about this failure you can read about by clicking on <this link>). However, he had little problem attracting interest in other countries. Unfortunately, in each case he ended up negotiating licence production with companies that wanted to break into the civil aviation marketplace rather than ones already established in it. A deal with the Canadian Can-Car company led to a single aircraft that only flew in 1945 (the CBY-3, to read about it click <this link>), while production in the Netherlands by the Aviolanda company, fell through altogether. In the UK the "Scottish Aircraft & Engineering Company" was formed in 1936 to build a version of the UB-14 to be called the "British Burnelli BR-Mk II". The design was initially presented in press releases with air cooled radial engines, but in 1937 the British Rolls-Royce inline, liquid-cooled Kestrel engines were mooted as powerplants instead. At the time there was huge unemployment in Scotland in the aftermath of the economic depression and there were various schemes to subsidise the setting up of factories in Scotland, especially in Glasgow and other towns along the River Clyde (Blackburn Aircraft was one company that took advantage of this, setting up a flying-boat factory at Dumbarton). It seems the Scottish Aircraft & Engineering Company hoped to take advantage of these schemes, although the only addresses listed in its many press advertisements were in London. These press adverts were prodigious and a lot of interest was whipped up for their 16-seat version of the Burnelli and the name was changed to "The Clyde Clipper", a reference to where they hoped to produce the aircraft (there was also to be a cargo-carrying version to be called the "Clyde Carrier"). With war clouds looming, in March 1937 they also advertised a bomber version¹, apparently to be called the "Clyde Corsair" and a fighter version, armed with the short-barrelled American Armaments 37 mm cannon in turrets, to be called the "Clyde Comet". All of this came to nought, the company collapsed with only a wooden mock-up of the Clyde Clipper to show for its efforts. The receivers were called in on the 26th of July 1937.

A press advertisement from 1937 showcasing the range of Burnelli-inspired projects the Scottish Aircraft and Engineering Company was working on. The "subsidy" mentioned in the text refers to the financial assistance that governments provided to most airlines during that period to make them viable. This was often in the form of payments for carrying air mail.

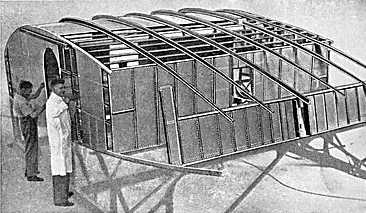

An image from another advertisement for the Scottish Aircraft and Engineering Company, purporting to show their "Clyde Clipper" under construction. In fact, it was just a wooden mock-up.

An image from another advertisement for the Scottish Aircraft and Engineering Company, purporting to show their "Clyde Clipper" under construction. In fact, it was just a wooden mock-up.

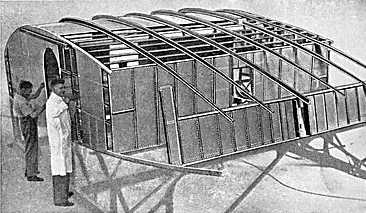

An image of the Scottish Aircraft & Engineering Companies "Clyde Clipper" wooden mock-up at their "Scotia Works" in Wembley, West London. Apparently, the inline Kestrel engine was simply a flat wooden panel painted to give a 3-D representation of the engine. The use of the Kestrel would have given a better view for the pilots than that afforded by the Perseus radial-engined Cunliffe-Owen OA-1. There was a recess in the underside of the wing to allow full access to the door which would otherwise have had to be uncomfortably small. You'll see that the Scottish Aircraft "Clipper", with its slender tail booms, looks much more like the original Burnelli than the later Cunliffe-Owen OA-1. The Scottish Aircraft and Engineering company should not be confused with "Scottish Aviation Limited" which was based at Prestwick in Scotland. That was an entirely different company that specialised in training and only moved into aircraft maintenance and manufacturing during the war.

A Youtube video of a contemporary newsreel shows the mock-up of the "Clyde Clipper".

A Youtube video of a contemporary newsreel shows the mock-up of the "Clyde Clipper".

Magazine Cover illustration of Scottish Aircraft and Engineering Company "Clyde Clipper" with inline Kestrel engines.

The January 1937 advert for the "British Burnelli Medium Bomber BR Mk IV" features a photo of the Burnelli UB-14B with some extravagant claims for performance and a promise of delivery within 6 months. The project was later renamed the "Clyde Corsair".

An approximation of the Scottish Aircraft and Engineering Company's " Clyde Comet" fighter. It was designed to have a single 37mm cannon firing forward and another two in ventral positions firing to the rear with "machine guns as secondary armament". The cannons, made by the American Armaments Company of New York, were a truly dreadful design. The gunner sat side-on to the cannon, looking sideways to aim, while manipulating two hand cranks, one to traverse the cannon and another to elevate it. The cannon itself was fired by a foot pedal. Clips of 5 rounds had to be manually loaded, but if there was a misfire, the weapon was rendered useless because it required two people to recock it with a special tool, something that could only be done on the ground. The weapon was a development of the French Puteaux trench gun of WW1, adapted for automatic operation. The recoil mechanism decreased the already low muzzle velocity to give it poor range and penetration. It was widely featured in aviation journals in the 1930s with exaggerated claims made for its performance (rates of fire of 120 rounds a minute were claimed, ignoring the fact that clips had to be reloaded after every 5 rounds). In use on the Clyde Comet fighter, you have to wonder how it would avoid shooting off the propellers! The cannon was also used on another aborted project, the American Tucker armoured car.

The January 1937 advert for the "British Burnelli Medium Bomber BR Mk IV" features a photo of the Burnelli UB-14B with some extravagant claims for performance and a promise of delivery within 6 months. The project was later renamed the "Clyde Corsair".

An approximation of the Scottish Aircraft and Engineering Company's " Clyde Comet" fighter. It was designed to have a single 37mm cannon firing forward and another two in ventral positions firing to the rear with "machine guns as secondary armament". The cannons, made by the American Armaments Company of New York, were a truly dreadful design. The gunner sat side-on to the cannon, looking sideways to aim, while manipulating two hand cranks, one to traverse the cannon and another to elevate it. The cannon itself was fired by a foot pedal. Clips of 5 rounds had to be manually loaded, but if there was a misfire, the weapon was rendered useless because it required two people to recock it with a special tool, something that could only be done on the ground. The weapon was a development of the French Puteaux trench gun of WW1, adapted for automatic operation. The recoil mechanism decreased the already low muzzle velocity to give it poor range and penetration. It was widely featured in aviation journals in the 1930s with exaggerated claims made for its performance (rates of fire of 120 rounds a minute were claimed, ignoring the fact that clips had to be reloaded after every 5 rounds). In use on the Clyde Comet fighter, you have to wonder how it would avoid shooting off the propellers! The cannon was also used on another aborted project, the American Tucker armoured car.

To pick up the pieces, in stepped Sir Hugo Cunliffe-Owen, a flamboyant industrialist and racehorse owner who had been planning to use a "Clyde Clipper" for his own attempt at winning a New York to Paris air race². He purchased the rights to produce the Burnelli design, establishing "B.A.O. Ltd" * to build the aircraft in August 1937. Construction of the prototype was to begin soon afterwards in an existing hangar (hanger 2A) at Eastleigh near Southampton. The name of the company was changed to "Cunliffe-Owen Aircraft" on the 24th May 1938. At the same time, work started on the construction of a a brand new state-of-the-art aircraft factory at Eastleigh to build the new design in quantity.The new factory was formally opened by the Mayor of Southampton on the 23rd of January 1939. The choice of Southampton may seem strange given the subsidies available in Scotland, but in the late 1930s "Red Clydeside" had a bad reputation for industrial relations. Meanwhile, the Southampton and Solent area was already the home of many aviation companies like Supermarine, Saunders-Roe and Airspeed and promised to have a ready-made skilled workforce available.³ Some sources claim the building of the new Cunliffe-Owen factory was subsidised under the "shadow factory" scheme but it is not at all clear if that was the case; it is not on any of the lists of such projects. It seems unlikely that Cunliffe-Owen got any public money for the initial building of the factory.

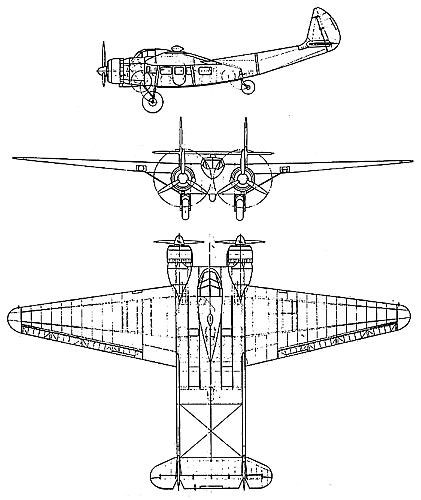

Sir Hugo had the Burnelli redesigned to use two of the new Perseus sleeve-valve radial engines made by the Bristol Engine Company. The redesign was supervised by William Garrow-Fisher, who had joined Cunliffe-Owen from the defunk Scottish Aircraft and Engineering Company along with some other staff. The Cunliffe-Owen "Flying-Wing" design was substantially different in structure and larger than the original Burnelli UB-14B and Scottish Aircraft "Clyde Clipper" mock-up. The future of the new aircraft initially looked bright. It promised to have a similar performance and load-carrying capacity to the Douglas DC-2. It took up substantially less hanger space than the DC-2 and offered passengers a comfortable "wide-body" cabin with large picture window views of the ground, unobstructed by the wings (the novelty of air travel and the better views of the ground available at the lower altitudes airlines then flew at meant the view for passengers was considered a very important factor in selling tickets).

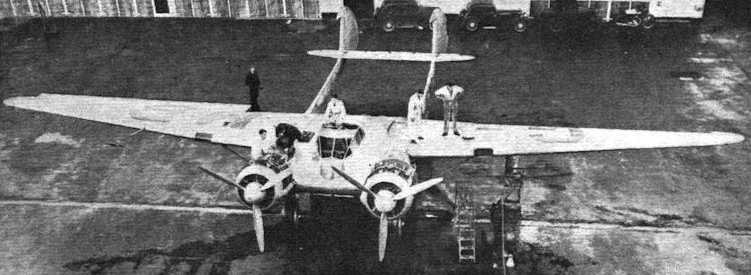

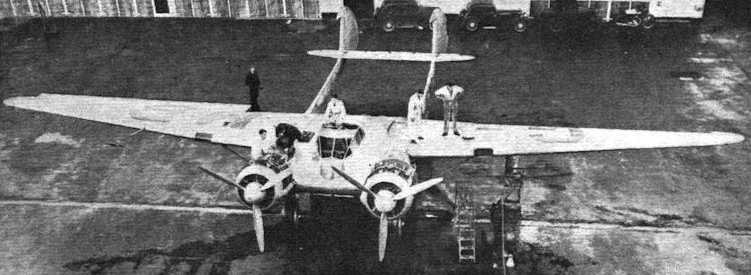

On the wet tarmac at Eastleigh, outside the stunning brand-new Cunliffe-Owen factory (soon to be the target of German Luftwaffe bombing) the Cunliffe-Owen OA-1 "Flying Wing" prototype G-AFMB is inspected by factory staff and admirers. You can appreciate how the twin Perseus radials cut off large parts of the pilot's forward view. Note also the much thicker wing booms than the earlier UB-14 and "Clyde Clipper" mock-up. The OA-1 was designed to float if it had to ditch in the water. There were doors in the roof of the cabin to allow passengers to clamber out onto the top of the wing in such an eventuality.

Another benefit of the Burnelli layout was that, with suitable ballast in the rear of the passenger compartment, you could detach the twin tail booms while still leaving the fuselage standing on the tailwheel. They built provision for this into the design. (you can make out the join-line for the tail running between the "A" and "F" serials on the tail boom in the photo above).

View of the OA-1 showing the poor sideways view from the cockpit for taxiing. Note the bracing struts under the wings and the height of the passenger door above the ground, requiring steps for boarding.

Unfortunately, Sir Hugo's timing for starting construction of a new aircraft type could not have been worse. As war clouds gathered, all the established aircraft companies found themselves with full order books and aircraft designers, production staff and skilled workmen became scarce. This was to have dire consequences for the new OA-1 Flying Wing. The design and building of the prototype was completed within the remarkably short time of 18 months, but this was still longer than anticipated and it was subsequently slated for a host of detail design flaws and bad workmanship in its construction. By the time the prototype first flew on 12th January 1939, piloted by Clyde Pangborn, the new Douglas DC3 had long replaced the DC2 on the production line and set new standards of performance and economy. The rival British deHavilland DH91 Albatross and Armstrong Whitworth Ensign airliners were already in service and the prototype deHavilland H95 Flamingo, aimed at the same market as the OA-1, had flown the month before. New designs in the pipeline with pressurised passenger compartments like the Douglas DC-4, Curtiss CW-20 and Fairey FC1 looked set to make the OA-1 obsolescent even before it entered service. It is clear now that the OA-1 was three or four years too late to make any impact on the civil aviation marketplace.

The Cunliffe-Owen OA-1

Another view of the OA-1 outside the Cunliffe-Owen factory.

The OA-1 in flight over Southampton Docks.

Another view of the OA-1 outside the Cunliffe-Owen factory.

The OA-1 in flight over Southampton Docks.

Some sources assume that the OA-1 was assembled from parts shipped over from the USA. There is no evidence for this. The engines were made in Britain, as was the undercarriage. Lots of British companies advertised in the aeronautical press that their products were being used in the OA-1. At the time, currency exchange rates and labour costs meant that items manufactured in the USA could be double or triple the cost of the same items made in the UK, and that is without the extra costs of shipping. So it would have been uneconomic to ship in parts from America.

Cunliffe-Owen OA-1 in flight.

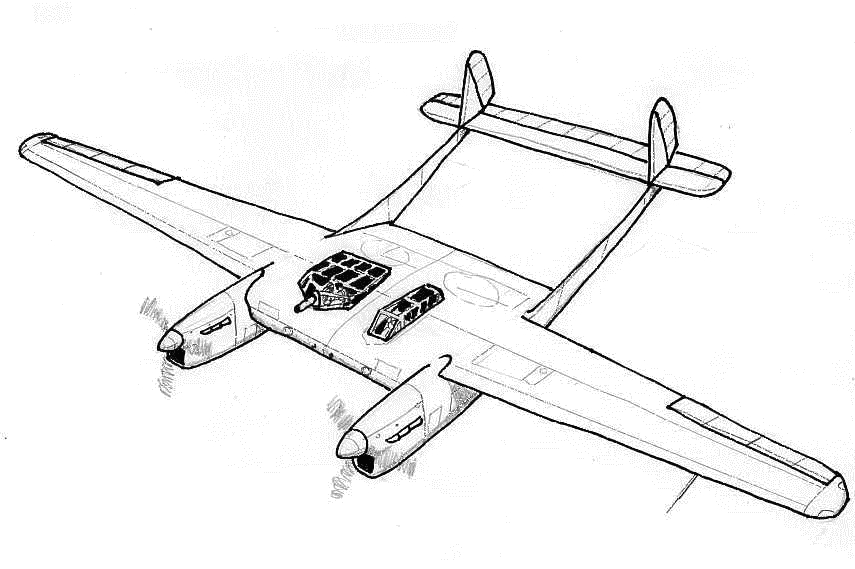

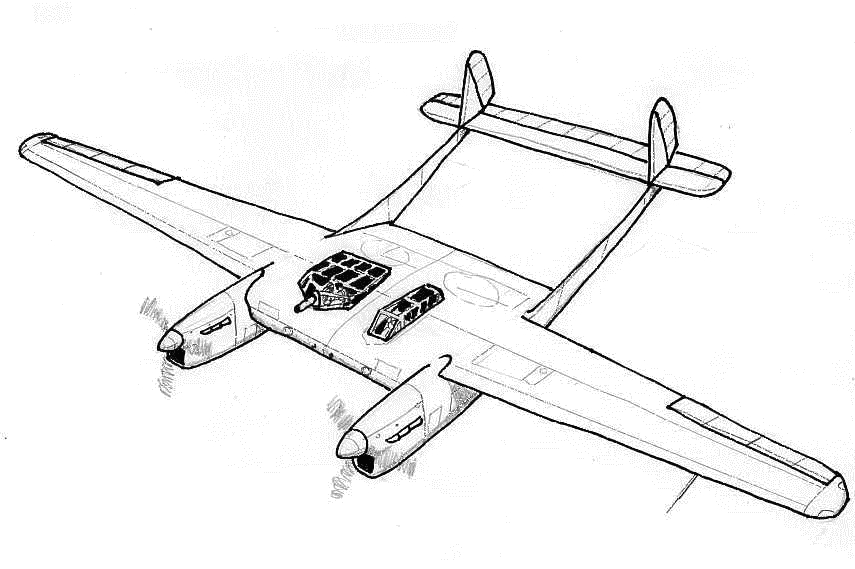

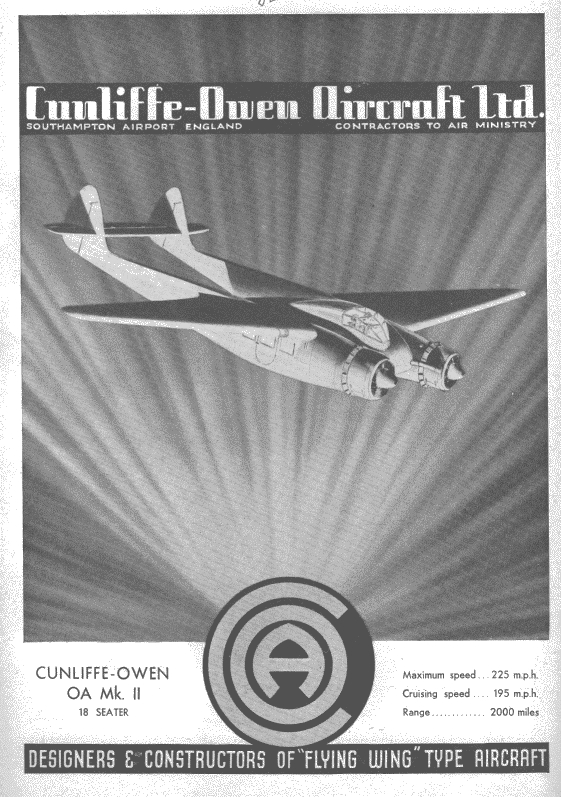

It must have been evident to Cunliffe-Owen that the OA-1 had shortcomings, because late in 1939, they advertised a proposed OA "Mark II". This had tail booms that were thicker (thick enough to accommodate a toilet in one boom and an extra cargo hold in the other) and did not require cross-bracing wires between them. The booms were not angled up, so the tailplane was in line with the wings, giving the Mk II a more streamlined look.

Advertisement for the proposed "Mark II" version of the Flying Wing. Notice the tail booms are straight, making the aircraft look more streamlined.

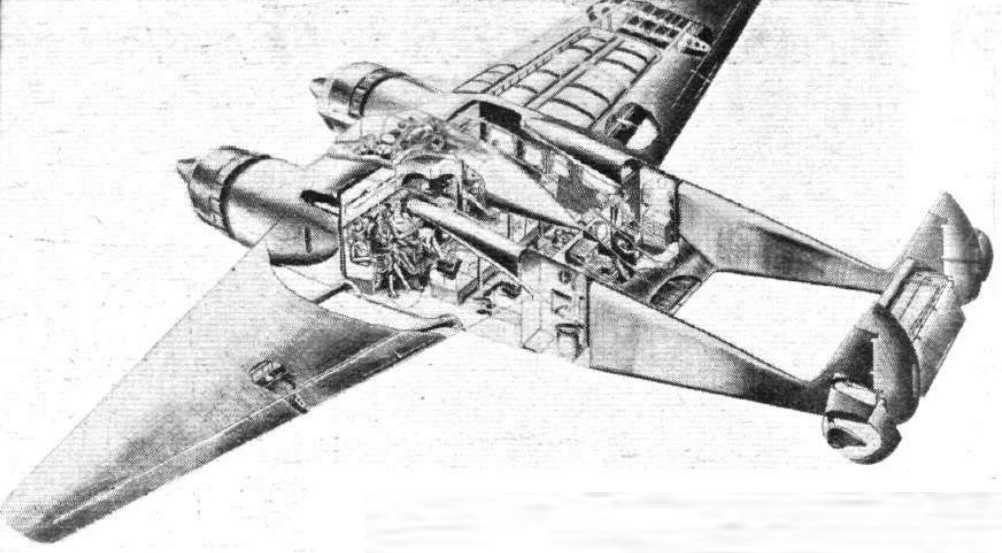

Blurred cutaway diagram of the proposed Mark II Flying Wing. You can just make out that the added thickness of the tail booms allows a toilet to be accommodated in one and extra baggage to be carried in the other.

In June 1939, the Cunliffe-Owen OA-1 went to the Aircraft and Armament Experimental Establishment (AAEE) at Martlesham Heath for evaluation and certification. Testing continued until after the outbreak of war. Its flying qualities, although not perfect, were generally adequate for a prototype aircraft, and its short landing run was remarked upon. However, as already mentioned, many aspects of the detail design were condemned, and the construction and workmanship were found to be woefully poor. The poor ergonomics of the cockpit, the flimsiness of the passenger windows and the lack of any anti-corrosion protection came in for particular criticism. It was refused a Certificate of Airworthiness (CofA) and returned to the manufacturer's Eastleigh factory. If Sir Hugo's timing for constructing the prototype OA-1 was disastrous, his timing for building a brand-new aircraft factory could not have been better. In 1939 the factory had beem employed in the assembly of Lockheed 14 airliners for British Airways. When war was declared, his factory space became much in demand, and production from other manufacturers (notably Supermarine who shared the Eastleigh airfield with Cunliffe-Owen) and the need to reassemble aircraft shipped over from the USA into the port of Southampton soon filled it to bursting. There would have been no space to produce the OA-1 even if it had been a success. The Cunliffe-Owen factory was severely damaged by the German Luftwaffe during the Battle of Britain, but it was subsequently repaired and continued in use throughout the war, including being used for the construction of 250 examples of the Seafire Mk III. The Cunliffe-Owen Seafires were particularly valued by pilots because they were completely flush-riveted, giving them better performance than those built by other companies.

OA-1 coming in to land. Of particular note is the fuselage flap, this gave the aircraft a remarkably good short-field performance on landing. The fuselage and wing flaps could be operated separately to each other, although they had only two positions "up" or "down".

What to do with the OA-1 prototype? The company did find time to fix many of its shortcomings. It was inspected by A&AEE again in March of 1940 and was granted a Certificate of Airworthiness late in 1940 (certificate number 6881). Since one of the major criticisms of its construction was the lack of any sort of anti-corrosion finish, what better place to use it than in a desert, where corrosion would be no problem! The aircraft was impressed into the RAF on 31st May 1941(although no RAF serial was allocated). In June 1941 it was piloted to North Africa by the dare-devil flyer Jim Mollison with a crew of three⁴, to join the Free French Forces. It was flown out by a circuitous route, via Gibraltar, Malta, Cairo, Wadi Halfa, Khartoum, El Fasher, El Geneina and Fort Archambault to Bangui. One source said that Mollison claimed to have flown the first leg to Malta over the length of occupied France⁵ (although it's hard to see how this could be done, except at night and the hours of darkness would have been very short in June). There were some doubts that it could have landed at Gibraltar since the runway there had not been lengthened for large aircraft at that time. However, the OA-1's short-field performance must have made it possible since an eyewitness account of it taking off from Gibraltar on the 6th of June 1941 exists⁶. A photo of the OA-1, reportedly in either Malta or Egypt, shows it to have camouflaged upper surfaces (that was normal for British civil aircraft at the time). It also shows it still to be wearing its civilian registration.

This photo of the OA-1 has been variously identified as being taken in either Malta or Egypt on its way to French Africa. A better photo, obviously taken at the same location, can be found in the Summer 2008 edition of Air-Britain Archive magazine, where it is identified as being in Malta. In the image above, you can clearly see the aircraft still has its British civil registration, G-AFMB, although official records show the registration was cancelled on the 6th of June 1941, the day it is recorded as leaving Gibraltar.

Rumours that the OA-1 was used by General Charles de Gaulle during his visits to French Africa are not backed up by any solid evidence (although de Gaulle did present Mollison with a jewelled cigarette case for ferrying the OA-1 out). The OA-1 was used for cargo carrying across French Africa, operated by Lignes Aériennes Militaires (LAM) a nominally civilian organisation, although dedicated to supporting the Free French military. Photos show that the air intakes under the engines were fitted with large air filters, similar to the ones used on Wellesley bombers, to protect them from the sand and dust of the desert. It was in service until at least June 1944, when it was apparently damaged at Rayaq in Lebanon, after which it was flown to Egypt for repairs. On VJ night 1945 it was languishing in the salvage compound at No 2 Transport Aircraft Repair Unit (TARU) at El Kabrit in Egypt, stripped of wings, engines and most interior fittings, it was burnt on a bonfire to celebrate the end of hostilities.

The OA-1 in Free French service.

And so ended the Cunliffe-Owen OA-1 "Flying Wing", although the company did continue to look into possible future developments. It is possible that the design they prepared for an Air Ministry 1943 specification for a twin-engined aircraft to operate off aircraft carriers (S6/43, later reissued as S11/43) had a "lifting fuselage" layout. An ambitious design for a post-war 4-engined transatlantic airliner that looked like the Lockheed Constellation fell through. Cunliffe-Owen reverted to a more modest conventional layout for their "Concordia" 10-passenger feeder-liner, the prototype of which flew in 1947. There was no market for such a new aircraft in a world awash with cheap ex-military transports like the DC3 Dakota and the failure of the project saw Cunliffe-Owen withdraw from the aviation marketplace. The death of Sir Hugo Cunliffe-Owen, in December 1947, also played a part in the winding-up of the company which went into receivership in July 1948. Some of the factory space continued to be used for the assembly of two Cierva W11 "Air Horse" helicopters by the G&J Weir company, the first of which flew in December 1948. The construction of the M27 motorway separated the Cunliffe-Owen factory from Eastleigh Airfield (now Southampton Airport). The site was occupied for many years by the Ford Motor Company, which built the Transit van there.

OA-1 over the Solent.

OA-1 Specifications

Engines: Two Bristol Perseus XIV-C single-speed, medium supercharged sleeve-valve radials of 710 horsepower each.

Max Speed: 218 mph (351 kph), expected to cruise around 180 mph (290 kph). Higher maximum and cruising speeds were advertised in Cunliffe-Owen's trade adverts.

Ceiling: About 20,000 ft (6,096 metres). Being unpressurised it could not have operated as a normal passenger aircraft at such heights unless the passengers were issued with oxygen bottles and were happy to experience the considerable discomfort experienced flying at such altitude without pressurisation.

Crew of two (pilot and co-pilot). Passenger capacity 20 (the prototype was fitted out for only 15 passengers in luxurious armchair seats made by the Rumbold company).

Fuel capacity: 650 gallons (2,955 litres) in eight wing tanks.

Maximum range: 1,300 miles (2092 km). Some sources quote a much higher figure of 1,950 miles (3,138 km) which seems improbably high for the amount of fuel carried as standard. It is possible that auxiliary internal fuel tanks were fitted for the flight out to Africa, giving rise to the latter figure. Or it could be that the higher expected range of the Mark II version was quoted instead.

Span: 73 feet 6 inches (22.4 metres). Length: 44 feet (13.4 metres).

The Mk XIV-C version of the Bristol Perseus sleeve-valve engine used on the OA-1 was a civil-rated engine that produced substantially less power (710 hp) than the military Perseus XII. (905 hp), although some of Cunliffe-Owen's trade adverts quoted the military figure.

WHAT IF?

The Cunliffe-Owen OA-1 Flying Wing was almost certainly too late to be a success in the civil marketplace. By the time it was ready to fly, it was already 3 or 4 years behind the times in terms of performance and economy. When Burnelli had first flown his UB-14 design in 1934, it was cutting-edge. If he had successfully negotiated production rights with established aviation firms straight away, he might well have produced a winning product that would have gone down as one of the greats of aviation history, but the delay in dealing with "start-up" companies meant he missed the boat, and the great promise of the basic UB-14 design was lost. It is interesting to speculate what might have happened if he had got established British aviation companies interested in producing his designs. Ironically, quite a few British aircraft companies were casting around for new civil designs to build at the time the Burnelli design became available and before their order books filled up with military contracts for the coming war. Avro had produced the Type 618 airliner and later variants based on licences purchased from Fokker, while Vickers had been building a progression of "Viastra" airliner designs based on technology licensed from Michel Wibault; both were coming to the end of their development potential just as the UB-14 became available. The Westland Aircraft company had recently given up on the development of their Wessex trimotor, and their experience with building the abortive Westland Dreadnaught blended-fuselage aircraft might have been applicable to the Burnelli designs. If the UB-14 and its derivatives had reached production in the USA and UK as early as 1936, maybe it could have taken its place alongside the C-47/DC3 Dakota in the air forces of the Allies?

My painting shows the Cunliffe-Owen OA-1 as if it had gone into production and been used as a transport aircraft by the RAF in WWII. In this case shown dropping paratroops. I've fudged the problem of exiting by not showing the doorway the paratroops are jumping from. On the original design if you had jumped from the standard door you would have gone straight into the rear wing support strut! I have reasoned that a smaller parachute door would have been positioned to the rear of that strut or in the floor of the aircraft.

Looking at the Cunliffe-Owen OA-1 in isolation, it is tempting to speculate that if Sir Hugo had been able to get the quality of staff he needed he might have got the OA-1 prototype flying a little earlier, and without the myriad design and construction flaws it actually had, so it could get a Certificate of Airworthyness in early 1939. Under those circumstances, it's possible to imagine aircraft starting to come off the production line of the new factory about the time the war started (first deliveries would probably have gone to Olley Air Services, an airline and aircraft taxi service that Sir Hugo Cunliffe-Owen had the major shareholding in). Even then, it's probable that the Air Ministry would have only allowed a limited production run before turning the factory over to bomber or fighter production (production of all the promising British transport aircraft, DH91 Albatross, DH 95 Flamingo and AW Ensign were all stopped after only a few examples). The Air Ministry simply did not foresee that the new World War would demand huge numbers of transport aircraft; it thought the outcome of the war would be decided within weeks or months of war being declared by massive bombing by the competing fleets of bomber aircraft.

Of course, it is possible that if the OA-1 or the proposed Mark II had made it into production, the design might have been adapted for more warlike uses, although only as an interim stop-gap. Hence the flight-of-fancy painting below.

This painting shows the OA-1 as it might have appeared if it had been pressed into service by RAF Coastal Command. Such a thing is not at all unlikely if it had been in production. The Lockheed Hudson was a conversion of an airliner, as was the Avro Anson, both of which were used by Coastal Command. Also, a conversion based on the Douglas DC2 airliner called the B-18 Bolo was used for coastal/ocean patrol by the Canadian Air Force (who called it the "Digby") and was also used extensively by the USAAF for the same role in the Caribbean.

One thing is sure, if it had gone into production, being built in Southampton, the OA-1 would have never been called a "Clyde Clipper". Perhaps a better name would have been "Solent Schooner"!

Interestingly, the modern UAV drone produced by Windracers, which has been used for deliveries to remote islands and communities for the Royal Mail, has a lifting fuselage configuration very similar to the OA-1. It did its first trial flights to the Isle of Wight over the Solent. You can see a short YouTube video of it at <this link>.

Notes

¹ The Scottish Aircraft and Engineering Company's "bomber" was advertised with pictures of an unmodified UB-14 and seems to have been just their "Clyde Clipper" with minimum modifications to enable it to carry bombs. It should not be confused with the "Burnelli A-1 Bomber" which was a different project altogether, designed by Burnelli back in the USA with a more traditional looking fuselage nose projecting forward of the lifting fuselage with a bomb aimers position and a front turret. It also had much deeper tail booms able to accommodate a dorsal turret in each. The A-1 design was submitted for the US Army Air Corps 1935 competition for a new bomber, a competition won by the Douglas B-18 Bolo.

² The NewYork to Paris Air Race was due to be run in August of 1937, to commemorate the tenth anniversary of Charles Lindbergh's pioneering solo flight. In the event, the race was changed to run between Istres in France and Damascus because of a fear that accidents would discourage passengers for the flying boat services that were being planned to cross the Atlantic. The race was comprehensively won by the Italians, with Italian aircraft and crews taking first, second and third places. Sir Hugo's entry of a "Clyde Clipper" was featured in prominent advertisements in the aeronautical press in May 1937. This displayed amazing optimism by the Scottish Aircraft and Engineering company, who had no construction started on the aircraft that was due to fly in a major competition in only 3 months time! The advertisements said the crew for Sir Hugo's Clyde Clipper were to be provided by Olley Air Services, but one source claims he tried to recruit Amy Johnson for the enterprise. The commentary on this contemporary newsreel hints at a famous female perhaps piloting the aircraft.

³ Not only were the aviation workforce in the Southampton and Solent area very skilled, they were also noted for a general lack of union activity, which meant they were also relatively lowly paid (Read C.R. Russells "Spitfire Postcript" ISBN 095248580X).

⁴ Mollison and his crew were in the "Air Transport Auxiliary" (ATA). Although the ATA had ranks and usually wore uniforms, its members were still civilians; they had the same status as a civilian airline crew. It was highly unusual for an ATA crew to fly outside of British airspace.

⁵ See the article "Air France Libre" in the list of sources below.

⁶ See page 103 of "Wings at Sea", a wartime autobiography by Gerard Woods, although when he saw the OA-1 taking off from Gibraltar he assumed it was flying back to the UK. Published by Conway Maritime Press in 1985. ISBN:0851773192. Thanks to Brian Johnston for alerting me to this account.

* Does anyone know what "B.A.O." stood for? There are suggestions that the first two letters stood for "Burnelli Aircraft", but it seems much more likely that it stood for "British American" since Sir Hugo's primary company was British American Tobacco Ltd. If anyone can give me a definitive answer, please get in touch.

Links

A Youtube video of a contemporary newsreel shows the mock-up of the "Clyde Clipper".

Video of the Cunliffe-Owen OA-1 on the British Pathe Newsreel Website

You get a glimpse of the OA-1 in this video of French officers touring England in 1939.

The story of Cunliffe-Owen on the "Solent Sky" website.

Photos of the OA-1 under construction on the "1000 Aircraft Photos" website.

Cunliffe-Owen listing on the "British Aviation - Projects to Production" website.

Cunliffe-Owen Aircraft Ltd listing in "Grace's Guide".

This page on the "Hyperwar" website has an interesting description of the Amarican Armaments 37 mm cannon as planned to be used on the "Clyde Comet" fighter version of the "Clyde Clipper". You'll need to scroll down to pages 593 to 595 to find the description. It seems to have been a weapon with many disadvantages.

Video on YouTube of the damage to the Cunliffe-Owen factory after a Luftwaffe raid in September 1940. The Heinkel He111 had been shot down the previous month and was being stored at the factory at the time (it was on a tour of British towns for a fund-raising drive).

A Youtube video of a contemporary newsreel shows the mock-up of the "Clyde Clipper".

Video of the Cunliffe-Owen OA-1 on the British Pathe Newsreel Website

You get a glimpse of the OA-1 in this video of French officers touring England in 1939.

The story of Cunliffe-Owen on the "Solent Sky" website.

Photos of the OA-1 under construction on the "1000 Aircraft Photos" website.

Cunliffe-Owen listing on the "British Aviation - Projects to Production" website.

Cunliffe-Owen Aircraft Ltd listing in "Grace's Guide".

This page on the "Hyperwar" website has an interesting description of the Amarican Armaments 37 mm cannon as planned to be used on the "Clyde Comet" fighter version of the "Clyde Clipper". You'll need to scroll down to pages 593 to 595 to find the description. It seems to have been a weapon with many disadvantages.

Video on YouTube of the damage to the Cunliffe-Owen factory after a Luftwaffe raid in September 1940. The Heinkel He111 had been shot down the previous month and was being stored at the factory at the time (it was on a tour of British towns for a fund-raising drive).

Sources

"First of the Wide-Bodies?": A 4-page article by Peter London in the July-August 1995 (No 58) Edition of "Air Enthusiast" Magazine.

"Burnelli's Lifting Fuselages": A series of articles by Richard Riding that appeared in the March to July 1980 editions of the "Aeroplane Magazine". It is the June edition that covers the Cunliffe-Owen OA-1.

"The Cunliffe-Owen COA-1": An article in the "Head-On View" series (number 27) in the summer 2008 edition of "Air-Britain Archive" magazine.

"Air France Libre": An article by Michael West in the spring (March) 2011 edition of "Air-Britain Archive" magazine. It features a tiny picture of the OA-1 at 2TARU.

"Cunliffe-Owen Flying Wing": A two-page article in the Aircraft Described series (No143) in the July 1965 edition of "Aero Modeller" magazine (unattributed).

"A Lift Less Ordinary": A 5-page article by Peter London in the January 2016 edition of "Aeroplane" magazine.

"British Built Aircraft, Vol2, South West & Central Southern England": By Ron Smith, First published 2003 by Tempus.

"The Secret Years - Flight Testing at Boscombe Down 1939-1945": By Tim Mason, published by Hikoki. ISBN 0 951899 9 5

A letter from Norman Smith giving a detailed first-hand account of the ultimate fate of the Cunliffe-Own OA-1 at El Kabrit in Egypt was printed in the "Skywriters" letter pages of "Aeroplane Monthly" magazine in November 1979.

Article revised December 2025.