Dinger's Aviation Pages

The Successful British Aviation Company You've Probably Never Heard Of.

Simmonds Aerocessories, Spartan Aircraft, Oliver Simmonds and the symmetrical wing.

If you travel into London along the M4 Motorway, following the track of the Great West Road, as you go over the flyover through Brentford, along the so-called “Golden Mile”, you will pass a massive 1930s art deco style brick building with a central tower called Wallis House. Near the top of the tower, you will see the statue of an airman with what at first glance looks like angel's wing. A closer look will show that the wings belong to a large eagle-like bird perched on the airman's shoulder. The statue, called "Inspiration to Flight", is by the sculptor Donald Gilbert (not the notorious Eric Gill as is sometimes erroneously claimed). It is the impressive topping to what is still a hugely impressive building, built in the late 1930s as a factory and headquarters for one of Britain's most successful aeronautical companies. But which company could command such an impressive site in London? Vickers-Supermarine? Avro? Hawkers? - No, the building belonged to Simmonds Aerocessories, one of many sites it owned around the Britain and part of a group of companies that spanned the world, having large interests in the USA and Europe. The story is a fascinating one, dominated by Sir Oliver Simmonds, a man who reinvented himself multiple times.

Origins

Oliver Edwin Simmonds was born on Kings Lynn, Norfolk on the 22nd of November 1897. The oldest son of a church minister. His family later moved to Romford, a suburb of London, and he was sent to a boarding school in Taunton in Devon. It is said that the landing of an aircraft on the school playing field awakened his interest in aviation. In 1916 he joined the Royal Flying Corp as a pilot during World War I. serving with No 25 Squadron in France. Before joining up he had secured a scholarship to study history at Magdalene College of Cambridge University, but on being demobbed he managed to change this to study engineering instead, gaining his degree in 1922. While at University he had been active in its Aeronautical Society.

After graduation in 1922, he gained employment at the Royal Aircraft Establishment (RAE) at Farnborough. He got married the same year. Various sources claim that while there he wrote a groundbreaking paper on the transonic airflow around propellers in conjunction with an unknown female engineer. This seems to be a mistaken case of “Chinese whispers”, there is no record of him being the author of any such paper. What is known is that he is named as an assistant on experiments run by two of the leading scientists at Farnborough, George P. Douglas and R. McKinnon Wood, that resulted in a paper by them titled “The effects of tip speed on airscrew performance”. The “female engineer” associated with the experiments was almost certainly Francis Bradfield, who would go on to have a distinguished career running the wind tunnels at Farnborough. The paper was highly influential in establishing that as the speed of the tips of propellers approached the speed of sound, drag increased and the efficiency of the propeller decreased. The only paper that the Farnborough archives have records of Simmonds authoring was about wind tunnel tests on models of airships. After a couple of years in the research field at Farnborough, Simmonds moved to the department granting airworthiness certification to new civil aircraft. This enabled him to travel around the UK, visiting all the major aviation manufacturers, giving him a valuable insight into the workings of the industry and the latest technologies.

In 1925, The Supermarine company entered its sleek S4 floatplane, designed by R.J. Mitchell, into the Schneider Trophy race being held at Baltimore in the U.S.A. that year. Unfortunately, the S4 crashed on a test run before the race and the trophy was won that year by the Americans. Determined to try again, R.J. Mitchell cast around for talent to help with the design of a new aircraft. He apparently approached the Royal Aircraft Establishment to see if they could suggest anyone and Simmonds was put forward. He agreed to join Supermarine and moved to Woolston near Southampton with his wife. Just what role Simmonds played in the design of Supermarine’s next Schneider entry, the S5, is unknown. There is just one anecdotal story that Simmonds determined the fuselage cross-section of the S5 by sitting with his back to a piece of plywood and asking someone to trace around his outline. Because Simmonds was of slight build, this meant the S5 was an extremely tight fit for pilots to get into (the preceding S4 floatplane had quite generous cockpit dimensions).

The S5 was not ready for the Schneider Trophy competition held in the U.S.A. in 1926, but one source suggests that Simmonds went to America as an observer to see what technologies other countries were using in their new designs, and while there he struck up some contacts that would be useful in his later enterprises. In November 1926, Simmonds featured in newspapers reports in the UK when he was ordered to pay £50 and 16 shillings (worth about £2,500 today) in compensation after he rattled a fence at some children who were disrupting his tennis game, causing one of the children to fall out of a tree and sustain injuries. In September 1927, the S5 won for Britain at the Schneider race in Venice, Italy.

Supermarine S5

While working at Supermarine, Simmonds had developed an idea for a new design of light aircraft. The novel features of this aircraft allowed the individual sections to be built in confined spaces, which meant that Simmonds could start construction of a prototype in his own house. At some stage, Supermarine discovered what Simmonds was doing. They considered it unacceptable that Simmonds was working on another aircraft while working for Supermarine. In July 1928, it was announced that Simmonds was leaving the Supermarine to start his own company. This was three months before the next Schneider race, where the follow-on Supermarine S6 won for Britain.

Simmonds Spartan and the symmetrical wing.

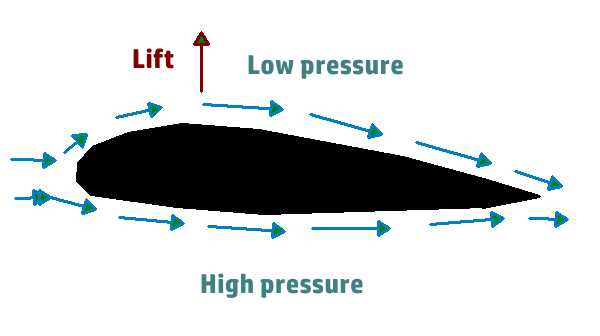

How does an aeroplane fly? You are probably aware of the usual explanation, usually accompanied by an illustration like that below; showing that the low pressure above the curved top to an asymmetrical wing profile generates lift.

The "normal" asymmetrical wing profile that generates lift by the airflow having to take a longer route across the top, curved surface of the wing.

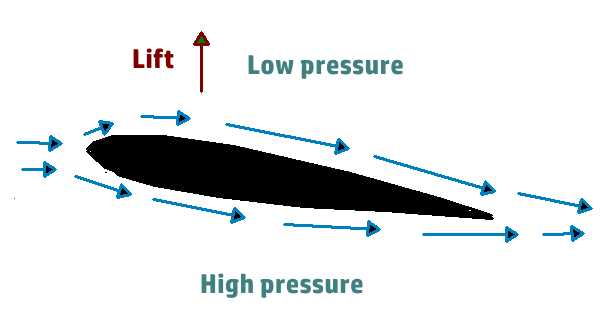

However, the same effect can be caused by a symmetrical wing profile if it is held at a slight angle to the airflow. Such a wing usually generates a bit more drag than the asymmetrical wing profile, but at speeds below 150 mph (approx. 240 kph), the extra drag is negligible.

A symmetrical wing profile can also generate lift if it is held at an angle to the airflow, and has the advantage that the wings of an aircraft can be made "swappable".

The advantage of a symmetrical wing is that it makes construction of an aircraft much easier and cheaper. The left wing can be identical to the right wing, just being flipped over to fit on the other side of the fuselage; something impossible with an asymmetrical wing. On a biplane, all four wings, top and bottom, can be identical. They can all be made on the same jig and that jig takes up half the space than having different jigs for each wing. This means that construction can take place in a much smaller space than with a traditional aircraft (one of the reasons Simmonds could start making his prototype in his own house). Another big advantage is that if you operate a fleet of such aircraft, you needed only to store one spare wing to have a ready replacement for damage to any of the wings of the fleet. This was of obvious benefit to the many flying clubs that proliferated during the 1920s, who often owned numbers of the same model of aircraft. Simmonds expanded on this advantage by making the half elevators and rudder all identical. He even made the undercarriage struts in two identical halves. All the bracing wires were made in standard lengths so that they could be interchangeable.

GIF animation showing how the interchangable parts made up the airframe of the Simmonds Spartan.

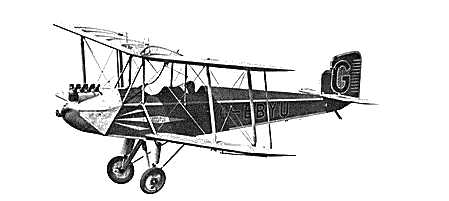

Simmonds built the two-seat prototype with the help of a Thomas Hiett, a skilled woodworker. He was also helped by some workers from the Supermarine factory in their spare time. The fuselage was made in the lounge of his house and the wings in one of his bedrooms. The front door and window-frames of the house had to be removed to get the parts out. Final assembly was done in a building called “The Rolling Mills” before the aircraft was towed (with wings folded) to a field at Bartlock Heath. Its first flight was piloted by the Schneider Trophy winning Flight Lieutenant Sidney N. Webster. Unfortunately, it overran the small field on landing, but the aircraft was easily repaired. Named the “Spartan” and registered as G-EBYU in time to take part in the King’s Cup air race on July 20th to 21st of 1928. Piloted by Webster again, it came in 17th, a creditable performance for a brand-new aircraft design.

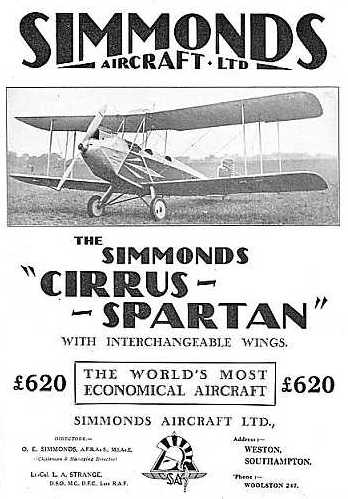

Press advert for the Simmonds Spartan (with a Cirrus engine), "with interchangeable wings". Note that Simmonds is already an Associate Fellow of the Royal Aeronautical Society.

The Spartan attracted the attention of the pioneer aviator Louis Strange. He had been looking for a new aircraft for himself, but was so taken with the Spartan, and the concept behind it, that he partnered with Simmonds to bring the new design to market. In October 1928, Strange flew as passenger with H. W. R. Banting, chief flying instructor of the Purbeck flying club as pilot, to the Berlin Air Show in Germany. On the way back they established an unofficial record of 5 hours 55 minutes for a flight from Berlin with a passenger. This produced a lot of publicity for the Spartan aircraft.

Simmonds Spartan

Simmonds Spartan Specification.

Max Speed: 100 mph (161 kph) , Cruising Speed: 85 mph (136 kph), Range: 320 miles (515 km).

Speed and range differed slightly according to the engine type fitted.

Empty Weight: 940 Ibs (426 Kg), Loaded Weight: 1,680 lbs (762 Kg).

Wingspan: 28ft 7 ins (8.71 metres). Length: 23ft 11ins (7.29 metres).

Simmonds Spartan Specification.

Max Speed: 100 mph (161 kph) , Cruising Speed: 85 mph (136 kph), Range: 320 miles (515 km).

Speed and range differed slightly according to the engine type fitted.

Empty Weight: 940 Ibs (426 Kg), Loaded Weight: 1,680 lbs (762 Kg).

Wingspan: 28ft 7 ins (8.71 metres). Length: 23ft 11ins (7.29 metres).

Production at the Rolling Mills site then started, with the major components then being shipped to the airfield at Hamble for final assembly and flight. Just how many were built to full flying condition is open to debate, but 48 seems the most likely total. A large proportion (25) were sold to overseas customers, a lot operating out of remote sites where the easy interchangeability of parts and small spare parts holdings would have been appreciated. 23 were registered in the UK, including a fleet of 12 ordered by National Flying Services for training purposes. Three Spartans were built with three seats, with two passengers facing each other in an enlarged cockpit ahead of the pilot. The prototype had been fitted with a 95 hp Cirrus III engine but production aircraft had various engines, Gipsy I (100 hp), Gipsy II (120 hp), ADC Hermes I (100 hp) and ADC Hermes II (105 hp).

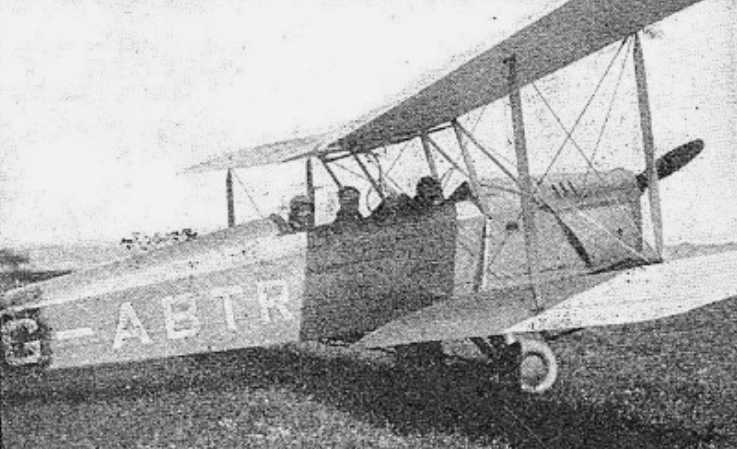

This Spartan was purchased for evaluation by the South African Air Force. Notice the symmetrical wing profile, angled up from the direction of flight.

All of these Spartan aircraft were built and delivered within the space of 15 months, a remarkable achievement for a new aircraft company. But then orders dried up. This was blamed on distrust of the symmetrical wing. To counter this, Simmonds did a major redesign to produce the “Arrow”. This was a two-seater that retained the interchangeability of the wings but they were given a “normal” asymmetrical profile by an ingenious system of detachable wingtips and trailing edges. The two halves of the undercarriage could still be swapped over, but the rudder was given a new design that was not compatible for swapping with the half-elevators.

Of course, in October 1929 the American Stock Market crashed and the Great Depression started. This had the effect of suppressing the purchase of all new aircraft. Coming, as it did, with the downturn in sales of the original Spartan design, this threatened to force the closure of the company before “Arrow” production had begun. The struggles of the Simmonds company attracted the attention of Whitehall Securities, a financial company which was looking to acquire a growing stake in the aviation marketplace. Prompted by Harold Balfour, a friend of Louis Strange, Whitehall Securities took a controlling share of the Simmonds company in 1930, renaming the company Spartan Aircraft Ltd. In February 1931, the company was moved from the Rolling Mill site at Weston to East Cowes on the Isle of Wight. This was part of a plan to merge the activities of the Spartan aircraft company with that of the Isle of Wight based Saunders-Roe (Saro) company, which Whitehall Securities also had an interest in. At first, the two companies were kept as separate entities, with Spartan concentrating on landplanes and Saro concentrating on flying boats. Oliver Simmonds still had a place on the board of Spartan Aircraft (along with Louise Strange). Arrow production had begun at the Rolling Mills site, with four being built there before production was moved to the Isle of Wight. In total, 15 Spartan Arrows were built.

A Spartan Arrow, recognisable by the different style of rudder to the original Spartan. It had a slightly greater wingspan and length than the original Spartan.

Alongside the Arrows, Simmonds had designed a new three-seat aircraft. This was effectively a three-seat version of the Arrow, with the Arrow’s configurable asymmetrical wings, but it retained the rudder of the earlier Spartan, interchangeable with the half-elevators. Like the earlier 3-seat version of the Spartan, the configuration was for the two passengers to be seated in an enlarged cockpit in front of the pilot’s position. 19 were built in this configuration before the layout was changed to the pilot being seated in front, with the passengers seated behind, 6 being built in this configuration and known as the three-seater Mark II. These 3-seater aircraft were a great success in operation, with the obvious cost saving of carrying two passengers instead of one on air-taxi and pleasure flights.

A Spartan 3-seater Mark II with the pilot seated in front of the two passengers. On the Mark I the pilot sat at the rear.

Simmonds design input on Spartan aircraft seems to have ended with the three-seater. The next aircraft to carry the Spartan name was the Spartan Cruiser, a small three-engined airliner. This stemmed from an initial design by Edgar Percival for Saunders-Roe which was transferred to Spartan when it was decided that Saro would concentrate on flying boats while landplanes were the responsibility of Spartan. Oliver Simmonds and Louis Strange stayed on the board of Spartan and then in turn became involved in the setting up of Spartan Air Lines, which used Spartan Cruisers for regular services between London and the Isle of Wight. Spartan Air Lines merged with United Airways to form British Airways Ltd at the end of 1935. The Spartan aircraft company name had stopped being used from 1935, when it was absorbed into Saunders-Roe.

Last aircraft to bear the Spartan name was the Spartan Cruiser trimotor. A neat design, it could carry up to 10 passengers (although 6 was more common). It had little, or no, design input from Oliver Simmonds, being initially designed by Edgar Percival.

Simmonds Aerocessories.

When Whitehall securities arranged the merger of the Simmonds Aircraft company with Saunders-Roe in 1931, Simmonds received a payout of some £10,000. That is worth about £600,000 today. That same year, Simmonds attended the Paris Air Show and saw a display featuring a system of rods to connect the control surfaces of an aircraft to the joystick and pedals, rather than the cables usually used. He realised the advantages of weight-saving and easier maintenance for this system in larger aircraft and so purchased the rights to the system for the rest of the world, outside France. He then arranged for manufacture of this new system in Birmingham. This was the start of Simmonds Aerocessories and its associated group of manufacturing companies. Simmonds would travel the world, visiting air and trade shows, looking for new products he could buy the rights to manufacture. Perhaps his most famous product was a new type of self-locking nut with a fibre insert that largely replaced the earlier cotter-nut. People of a certain age in the UK will still call these “Simmonds Nuts”, while today the most common form is the “Nyloc nut” ¹ that uses a nylon, rather than fibe, insert. New types of fastenings became a speciality of Simmonds Aerocessories, with them also manufacturing the metal insert “Pinnacle” locking nut and the “Spire” range of low-cost “speed-nuts” along with a host of different types of cowling fasteners. The Simmons Group also manufactured the “Fran” range of oil filters, non-slip rubber surfaces for aircraft wings, the "Simmonds-Goudime” range of navigational aids, amongst a host of other aeronautical accessories. One innovation pioneered by Simmons Aerocessories was the “Pactor” fuel gauge, which used an electronic means of measuring fuel quantities. Simmonds Aerocessories were also the first to market the “Surform” plane.

Manufacture of Simmonds products in the UK was subcontracted to a host of companies, many in Birmingham. Then Simmonds started its own factory at Treforest in South Wales where manufacture of many of its products in the UK were consolidated to. It was in 1936 that the huge Simmonds Aerocessories headquarters building started to be built on the Great West Road and some manufacturing took place at the site, with additions to the building taking place until 1942.

Sir Oliver Simmonds FRAeS, pictured in New York on the 29th May 1944 on his way to Australia (authors collection).

Even before WW2, Simmonds had expanded to companies outside the UK, including France, Poland, Australia, Canada and the USA. In 1941 the Simmonds Aerocessories company in the USA developed a prototype target drone with a 9 foot (2.7 metres) wingspan, called the OQ-11, it did not enter service. During the war, more companies in the USA were acquired by the Simmonds Group and in the post-war years even more American companies were added. It was said that in the 1950s and 1960s, every aircraft manufactured in western countries (outside the communist bloc) had parts made by Simmonds Aerocessories.

It should be noted that in April 1946, questions were asked in the House of Commons about the inordinate profits that Simmonds Aerocessories seemed to have made in the early war years. It would seem that it was deemed that the company had paid its full share of taxes and the matter was dropped.

In 1947, Sir Oliver Simmonds abruptly sold all his UK businesses to Electric and General Industrial Trusts. Later in the 1940s he sold his French interests, but kept his US and Canadian investments. His son, Geoffrey Simmonds, would later go on to be chairman and president of Simmonds Precision Products. The Headquarters building was sold to the British Overseas Aircraft Corporation (BOAC), so the statue on the tower continued to serve the aviation theme. In 1960 it was taken over by the Smithkline Beecham pharmaceutical company. Between 2005 and 2008 the building was converted into apartments.

Today, a number of companies around the world retain the Simmonds name but they all operate as separate entities.

Member of Parliament.

Amazingly, while running Simmonds Aerocessories and also being on the board of Spartan Aircraft, Simmonds still found the time to run as a Conservative to be a member of Parliament for the Duddeston ward in Birmingham in 1931. He won, overturning a big majority for the previous Labour MP. Duddeston, with its largely working-class population and what would now be called “Peaky Blinders” feel, was an unlikely constituency for the Conservatives to win in the grip of the Great Depression. There must have been something about this young ex-fighter pilot to appealed to the electorate. He went on to win again in the 1935 election. As an MP, he was often involved with aviation affairs. He visited Spain during the Civil War to see the effect of aerial bombing and formed the Air Raids Precaution Institute to formulate policies for dealing with bombing and gas attacks. It was therefore ironic that his Duddeston constituency was amongst the most heavily bombed in Britain during WW2, with its population greatly decreasing. During the war, much of his focus in Parliament seemed to focus on aviation and air raid matters, although he was also the chairman of the committee overseeing the brick industry, to ensure continuing supplies for building and repairs during the war and also planning for post-war reconstruction. He lost to Labour in the landslide election of 1945.

Link to a full list of Oliver Simmonds speeches and questions in Parliament.

Afterwards

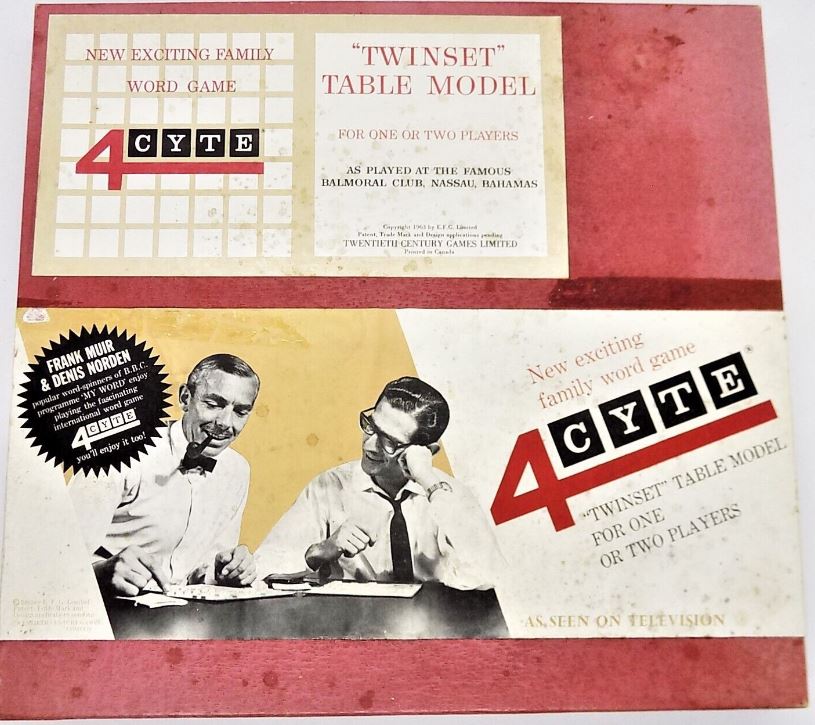

Simmonds had been knighted in early 1944 for services to aviation and politics. In 1948, having divested himself of most of his business interests in the UK, Simmonds moved to the Bahamas and reinvented himself as a hotel owner, founding the exclusive Balmoral Beach Club in the Cable Beach area of Nassau. To accomplish this, he had to set up his own construction company to do the work. The Balmoral club hosted many celebrity guest. While running the Balmoral, Simmonds invented a word game that he called 4CYTE (pronounced “foresight”), first released in 1962, that enjoyed some popularity for a time.

In the UK, the 4CYTE game was endorsed by the famous comedy scriptwriters Frank Muir and Denis Norden. In the USA the game had different packaging.

After the death of his wife, Simmonds moved to Guernsey in the Channel Islands in 1977, he remarried the following year. Oliver Simmonds died at the age of 87, on Friday 26th July 1985 at the Princess Elizabeth Hospital in Guernsey.

NOTES

¹ The principle behind the Simmonds nut and the Nyloc nut are the same, it’s just the material used in the insert that is different. Simmonds gained the rights to manufacture and sell the nuts in the UK and Commonwealth while the Elastic Stop Nut Corporation manufactured and sold them in the USA. The defining feature of the original fibre nuts was that the locking fibre insert should be of a red colour. This led to a court case in 1957 where the Elastic Stop Nut Corporation tried to stop Simmonds Aerocessories from importing lock nuts with a red insert into the USA. The judgement went in Simmonds favour.

LINKS

A full list of Simmonds and Spartan production on the Air-Britain website compiled by Malcolm Fillmore.

Graces Guide page on Simmonds Aerocessories with lots of the adverts used by the company.

Graces Guide page on Oliver Simmonds.

Copy of the Hampshire Airfields website page about Simmonds archived on the Wayback Machine.

Webpage about investigating the statue atop Wallis House, confirming it is by Donald Gilbert.

View of Wallis House from from the M4 on Google Streetview.

Photos of Simmonds Spartans in the Air-Britain archive

Photos of the last Spartan Arrow in the Air-Britain archive.

SOURCES

My interest in Simmonds was sparked by the Hampshire Airfields website by Dave H Fagan. Sadly, this has now disappeared although an archived copy can be found on the “Wayback Machine” – See link above.

My thanks to Les Ruskell of the FAST Archives at Farnborough for searching their records for mention of Simmonds.

A Biography of Sir Oliver Simmonds on the "Peoplepill" website <link here>.

An Obituary to Sir Oliver Simmonds that featured on the AP news website - It has now disappeared and it is not archived on the "Wayback Machine" - but a PDF copy of the text can be read at <this link>.

"British Civil Aircraft, 1919-59, Volume 2": By AJ Jackson, published by Putnam, 1960.

"Saunders and Saro Aircraft since 1917": By Peter London, published by Putnam in 1988. ISBN: 0 85177 814 3.

“Flying Rebel – The Story of Louis Strange” : By Peter Hearn, published by HMSO in 1994. ISBN 0 11 290500 5.

The Cheltenham Chronicle of 6th November 1926 is one of a number of newspapers that reported on Simmonds being ordered to pay compensations. My thanks to "Mikejee" on the Birmingham History Forum for unearthing this.