Dinger's Aviation Pages

BLACKBURN ROC

A short description and appreciation. Revised in December 2025.

Thanks to Mark E Horan for details of the Rocs operational use from HMS Ark Royal and Les Whitehouse for details of Boulton Paul's involvement with Roc production.

Seemingly always featured in lists of "the worst aircraft", the Blackburn Roc was an innovative attempt to provide an aircraft to deal with "fleet shadowing" aircraft at a time when the Royal Navy thought that warships could protect themselves from enemy aircraft with anti-aircraft (AA) fire alone. Produced in relatively tiny numbers, only a handful saw action. Yet they managed to account for one enemy bomber, were credited with damaging three more and drove off fleet-shadowing aircraft on two occasions. The only aerial combat loss of a Roc was a single one to enemy AA fire during a dive-bombing attack on gun batteries in France.

Overview

The Blackburn Roc was a development of the Skua fighter/dive bomber, designed to meet specification O.30/35 for a two-seat fighter with the added ability to "spot" for the gunfire of the fleet. It was initially meant to operate mainly on floats, being catapulted off battleships and cruisers, but also be able to operate off aircraft carriers. It was fitted with a rotating electric-hydraulic driven turret mounting four .303 Browning machine guns. This "type A" turret was manufactured by Boulton Paul, being based on the French-designed SAMM turret, for which Boulton Paul had secured a production licence. Boulton Paul already had some experience in aircraft turret production having produced the enclosed pneumatic turrets for the front gunner's position on the Boulton Paul Overstrand bomber (the first turret used by the RAF) and the company had also been responsible for installing the partially-enclosed Fraser-Nash FN-1 "lobsterback" turrets into late production Hawker Demon two-seat fighters. The production of the Roc was undertaken for Blackburn by the Boulton Paul factory at Pendeford on the outskirts of Wolverhampton. In all 136 Rocs were produced. The first production Roc serial number L3057 (there were no specially built prototypes) flew on 23rd December 1938. It must have been heart-breaking for Boulton Paul to be producing the Roc when their own turret-armed design, the Defiant, the prototype of which had first flown a year and a half earlier, was 80 miles per hour faster (Boulton Paul had tendered their own design to 030/35, the P85 with either Merlin or Hercules engines). Defiant production was underway from July 1939 and Rocs and Defiants were produced in the same factory for a year, the last Roc not being delivered until August 1940. The Roc differed from the Skua in having dihedral on the wings, doing away with the Skua's upturned wingtips, this improved stability. It carried no wing guns. The Roc featured a hatch in the floor for the gunner to use. The gunner did not wear his parachute when manning the guns (unlike in the Defiant where a special slimline "parasuit" with a built-in parachute was worn by the gunner) instead it was stowed in a receptacle inside the turret, near the gunner's knees, or on the inside of the fuselage for the gunner to clip on to the front of his harness before exiting through either the sliding doors at the rear of the turret or the floor hatch. The underside of the aft of the wings was flat, compared with the Skuas complex curved structure in this area. The Roc's propeller was of a slightly larger diameter than that used on the Skua, with an extra 3 inches (7.6 cm) on each blade, to try to improve speed and climb. However, with a modern understanding of transonic drag on propellers, Matt Bearman of the Whirlwind Fighter Project, speculates that this lengthening of the blades might have actually served to limit the top speed (see his article in Issue 35 of "The Aviation Historian" magazine). The Roc could be fitted with a "universal carrier" under each wing along with "light series carrier" bomb racks for up to eight 24 Ib (11 kg) "Cooper" bombs or 30 Ib (13.5 kg) incendiaries. The loads that each universal carrier could carry were listed in the pilot's notes as either a 250 lb (113 kg) "B" or semi-armour piercing (SAP) bomb or a 100 lb (45 kg) anti-submarine (AS) bomb or a bomb container. It was cleared for dive-bombing up to angles of 70 degrees. Although one of its roles was that of a fighter, the extra weight of the turret made it even slower than the Skua and in a level, stern chase it could not catch anything but the slowest of German seaplanes.

Design Philosophy.

For a whole article on the Royal Navy doctrines that led to both the Skua and Roc click <this link>.

For a whole article on the Royal Navy doctrines that led to both the Skua and Roc click <this link>.

In internet articles, magazine articles and books the one phrase that is used again and again about the Roc is that it was designed to "deliver a broadside" to an enemy aircraft. The author then usually goes on to ridicule the concept and make disparaging comparisons with three-masted sailing ships. The Roc, assuming it could catch up with its prey, would be much more likely to approach from below and try to bring its target down with no-allowance shooting, firing ahead and over the top of the pilot. The tactic of no-allowance shooting was very much at the heart of the philosophy behind the Roc and Defiant and yet it is hardly ever mentioned in descriptions of both aircraft, and the few articles available today on this subject only serve to obfuscate the principles behind it. However, one difference between the Roc and Defiant should be noted. The Defiant pilot had a gun button on the control column to fire the guns in the turret. There was a switch in the turret that could transfer control to the pilot, the intention being that the turret would be positioned facing forward, with the guns at an angle pointed upwards and then the pilot could fire the guns himself when he had an enemy aircraft in front and above him. The Roc pilot's notes do not show such a button on the control column. So it must be presumed this was not an option open to Roc pilots and they would have had to rely on the gunner to open fire once they were in a good position.

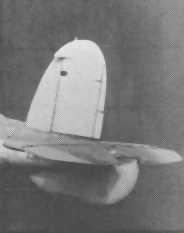

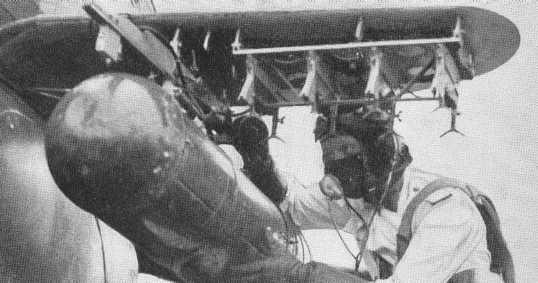

The Boulton Paul "Type A" turret fitted to the Roc. Normal entry was via sliding doors in the rear panels of the turret although entry via a hatch in the floor was also possible.

The thinking behind the Roc's design was heavily influenced by the Royal Navy's belief that the fleet at sea would be able to defend itself from air attack by anti-aircraft (AA) fire. The Navy invested huge amounts of money in this policy; building and converting a whole range of dedicated anti-aircraft cruisers that were designed to put up an impenetrable barrage of AA. For example, each of the Dido class anti-aircraft cruisers mounted ten 5.25-inch anti-aircraft guns in five turrets for high and medium defence (more AA guns than defended many British cities in 1939). For low-altitude defence, each Dido carried eight 2 pdr pom-pom guns in two quadruple mounts and eight large-calibre .5-inch machine guns in two quadruple mounts. Battleships and aircraft carriers even had eight 2 pdr pom-poms in single mountings! Anyone seeing an eight-barrelled pom-pom firing would be easily convinced that no aircraft within range could possibly survive.¹ It was considered that defending fighters would simply get in the way of the AA barrage and that turning an aircraft carrier into the wind and steering a straight course to launch fighters when enemy bombers were attacking would make the carrier extremely vulnerable. Of course, a "fleet shadowing" aircraft could stay outside the range of the AA barrage and radio back the fleet's position to the enemy, and it was to ward off this kind of aircraft that the Roc was designed (and indeed it was for that purpose they were used off Norway in 1940). You could regard it as a kind of flying machine gun post, flying around the fleet to extend the range of the AA barrage and ward off approaching enemy aircraft. A fleet shadowing aircraft would hope to avoid contact with opposing fighters by hiding in cloud cover, popping out every so often to keep contact with the ships it was shadowing. You can see that a traditional fighter with forward-firing guns might find it difficult to cope with this strategy if there is plenty of cloud cover to hide in. A turret-armed fighter has two pairs of eyes to search for the shadower and spot it as it flits in and out of the clouds, and the turret can be turned quickly to engage the target before it disappears again. Against such targets, fleet shadowing aircraft such as the Japanese Kawanishi E7K, Italian Meridionali Ro 43, German Heinkel He 60 or later Heinkel He 114, the Roc might have been a potent adversary, but in 1939/40 such designs were being superseded by faster and heavier armed aircraft such as the Arado Ar 196 and Aichi E13A which could outrun and outgun the Roc (although it should be noted that the A-1 version of the Arado Ar 196 used on German warships lacked the forward-firing cannon armament of the shore-based A-2 version). No sooner had the Roc been ordered than experiments with shipborne RDF (radar) held out the promise of being able to detect incoming enemy aircraft and launch fighters in time to intercept them. It was the advent of radar that changed the whole concept of air defence of the fleet.

The spotter aircraft the Roc was designed to counteract: On top is the Italian Meridionali Ro 43. On the left is the Japanese Kawanishi E7K and on the right is the German Heinkel He 60.

The other major role of the Roc was as a spotter for the guns of the big capital ships of the fleet. It was envisioned that a large majority of the production run would end up fitted with floats to enable them to be catapulted from the Royal Navy's battleships, battlecruisers and heavy cruisers. The Roc's turret armament was meant to defend it from attack by the spotter aircraft of the opposing fleet and enable the Roc to actively go after such enemy aircraft itself.

The Royal Navy also saw the Roc as an escort fighter to accompany torpedo bomber strikes against an enemy fleet, staying alongside the torpedo bombers as they went in for the attack. Such a scheme may seem laughable, but I wonder if the Swordfish crews that threw themselves against the Scharnhorst and Gneisenau in the "Channel Dash" might have appreciated an escort of Rocs to keep the Fw190s away for a couple of vital minutes? For that matter what about the Devastators and Avengers at Midway? Would an escort of a few turret fighters have kept the Zeros away for long enough for at least a few torpedoes to find their mark? Or would it merely have added to the slaughter?

Nice close-up shot of a Roc in flight. You can see the racks under the wings for both a 250 Ib bomb and the "light series" rack for up to four small bombs on each wing. The large lugs protruding from the bottom of the aircraft are attachments for the launch trolley used to catapult FAA aircraft from aircraft carriers early in the war. Although it had no forward-firing guns this Roc has a reflector gunsight for the pilot; this was also used as a sight when dive-bombing and allowed fighter training with a gun camera (carried in a small pod on top of the wing on the starboard side). The protrusion at the top of the front windscreen is a signal lamp (the Skua had this positioned on top of the canopy, near the aerial).

Production

The Roc was late going into production. It would seem that the Air Ministry tried to order it in 1936 against specification 26/36 but this was then cancelled, presumably because the Blackburn aircraft company was not in a position to fulfil the order. So it had to wait until the 28th of April 1937 before an order was placed (AM Spec 15/37, Blackburn contract number 534401). Even then Blackburn did not have the factory space required. Instead, all Roc production took place at Pendeford; Boulton Paul's factory and airfield complex on the outskirts of Wolverhampton (the airfield is now built over and Pendeford is now a suburb of Wolverhampton). Boulton Paul were given responsibility for the redesign of the fuselage to accept the turret. The Rocs were ordered in one batch of 136 aircraft allocated serial numbers L3057 to L3192. The first Roc flew on 23rd December 1938, but it was not until March 1939 that Rocs began to trickle off the production line and it was not until July 1939 that production seemed to have settled down to a steady flow. Boulton Paul were instructed that the production of Rocs must take priority over that of Defiants⁷. The last Roc off the production line was delivered in August 1940. Although there were no "prototype" Rocs, the first three Rocs, L3057, L3058 and L3059 were all tested extensively at the Aeroplane and Armament Experimental Establishment (A&AEE) at Martlesham Heath. The sixth Roc (L3062) was tested by the Navy at Worthy Down and found to be nose heavy, this was confirmed to be the case with the earlier Rocs as well and a modification to the tailplane incidence was introduced to correct it. Roc L3062 was used for trials onboard the carrier HMS Ark Royal in May 1939 (there is a photo of it landing on the Ark Royal in Stuart Lloyd's "Fleet Air Arm Camouflage and Markings" book).

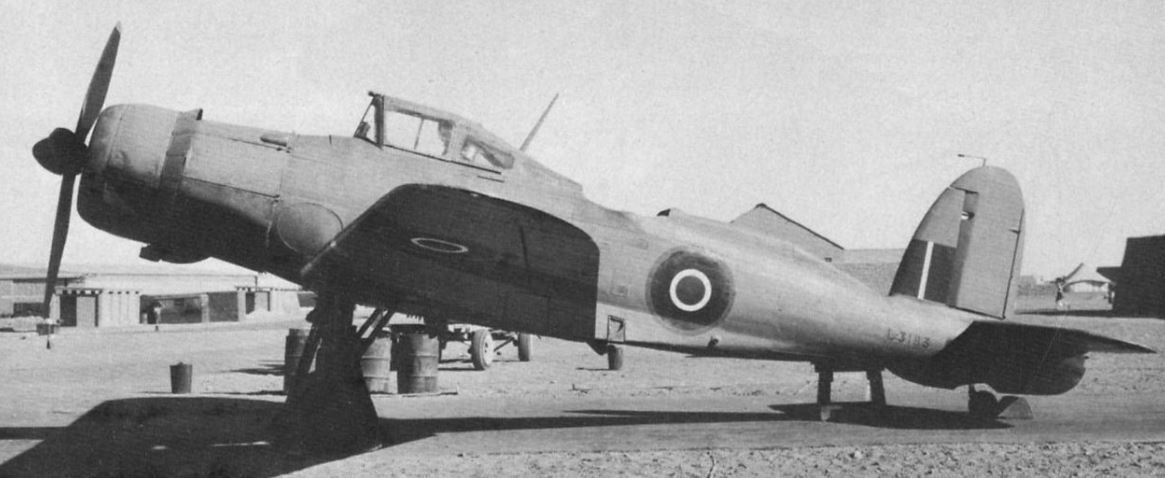

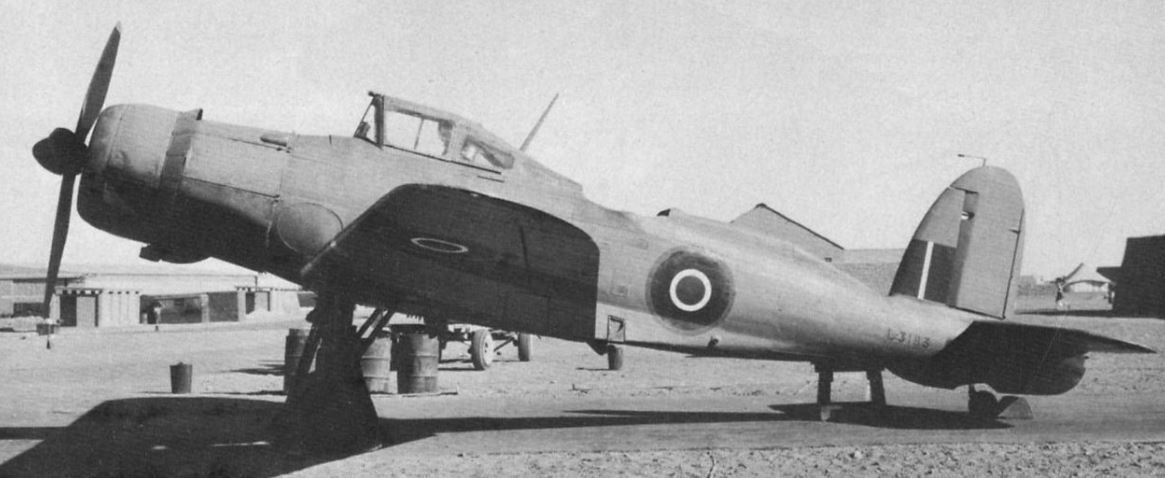

Early production Roc L3059, The Roc was a large aircraft; look how small the pilot looks in the cockpit. The two lines behind the landing light on the wing are two small strakes, a permanent feature on both the Roc and Skua; it was to these that the light bomb carriers were attached when needed. This is the first Roc to be fitted with floats. In December 1939, it crashed on test near the Blackburn factory at Brough on the river Humber. The aircraft was recovered and broken up for spare parts.

Floats

The Roc was designed to be fitted with a pair of floats of the same type as used by the earlier Blackburn Shark biplane. The provision of these floats was covered by Air Ministry specification 20/37. The small sea-rudders on the floats were operated by the brake pedals in the cockpit. The Roc was meant to be suitable for launching from the catapults installed on British battleships and cruisers. For such launches, the Roc's turret would be rotated so that the guns pointed forward and the sliding doors at the rear of the turret would be left open so that the gunner could brace the back of his head on a padded headrest built into the rear dorsal fairing. In August 1938, 4 months before the Roc first flew, it was already apparent that the Roc's lack of speed would make it a poor fighter. At a conference to discuss the situation, the Director of Air Material had suggested that Roc Floatplanes be allocated to the large capital ships of the Royal Navy, with no less than 3 Rocs apiece for Malaya, Warspite, Repulse, Renown, Queen Elizabeth and Valiant and a single Roc for Rodney.² This suggests that the Roc would have been used primarily as a spotter to replace the Fairey Seafox and Supermarine Walrus but with the added ability to ward off enemy fleet spotting aircraft. Five Rocs in the UK are known to have been modified with floats (there is only direct photographic evidence for four). It was found that the flying qualities of the first Roc with floats fitted (L3059) was poor (it was lost in a crash), but the fitting of a large dorsal fin under the tail improved the stability of the four other Roc floatplane modifications that are known to have followed in the UK (L3057, L3060, L3143 and L3174). The last of these operated with the turret removed and a target winch fitted. Research by Thomas Singfield and Ewan Partridge, for their book "Wings Over Bermuda", shows that some of the 5 Rocs operated by 773 FRU based on the island of Bermuda may have operated on "home-built" floats. L3069, the first Roc to arrive in Bermuda, was certainly fitted with floats (it arrived before the construction of Bermuda's airfield). Roc L3084 may have also have been trialed with floats by 778 Squadron at Lee-on-Solent.

Roc with floats fitted, this is the original L3056 which did not have a ventral fin extension. In many books and articles on the Roc, the use of floats is often presented as almost an afterthought; yet it was essential to the initial doctrine of having a catapult-launched spotter aircraft that could defend itself and also attack enemy spotters, as well as drive off enemy fleet-shadowing aircraft.

This picture shows the large ventral tail fin used on subsequent conversions.

Roc floatplane L3143 is rolled out of a hangar. The sheer size of the Roc is evident in this picture. Notice the undercarriage recess has been covered over but not painted. The enlarged ventral tail fin can be seen.

Cine-Camera

Roc (L3089) was modified with a special lightweight turret, stripped of gun equipment, to take a cine camera for air-to-air filming. Photographs of it show that the section between the front cockpit and turret was modified so that it could not retract. The Roc in question ran into a petrol bowser in March 1941 and then had a landing accident in December 1942 (details at this <link> ). It went on to have another two landing accidents. It saw service until May 1944, being one of the last Rocs to be retired. Photographs of another Roc, L3186, show it had a similar modification.

Roc L3089, with a turret adapted for a cine camera and a modified fairing between the front cockpit and the turret. L3089 was one of the longest serving Rocs, not being retired until May 1944, although it had 4 major accidents during its career.

Late production Roc L3186, photographed in a pristine camouflage finish. Notice the turret, stripped of guns, and the modified area between the turret and front cockpit. It lacks the "triangular" windows of the standard Roc and does not retract. This Roc was used by 771 Squadron in the Orkney Islands. It crashed with the loss of both crew members in December 1941.

Radio Equipment Mystery.

The radio equipment to be carried by the Roc was originally specified as an R1082 receiver with a T1083 transmitter. This was the same as the Skua, except the Skua also had an R1110 receiver set which was capable of homing in on the rotating beacon carried by British aircraft carriers and installed at some shore stations. The specification does not mention the R1110 homing receiver as fitted to the Skua. However, the R1110 set was considered "Top Secret" and so may simply have been left off the original specification to hide its existence.

The combination of R1082 and T1083 allowed communication by Morse code (both the pilot and gunner were provided with Morse "keys", the gunner actually operated his from within his turret). The R1082/T1083 radio equipment did provide an "intercom" between the pilot and gunner, so they did wear earphones and had microphones in their oxygen masks. As a backup, the Roc was to be fitted with a "Gosport" speaking tube. The R1082/T1083 was perfectly capable of being used for speech communication, either to another aircraft or back to a ship, if the equipment was fitted with the necessary coils. However, the Royal Navy doctrine of enforced radio silence meant that speech communication was discouraged, to the extent that the official manual for the T1083 transmitter advised that the microphone transformer be shorted out by a piece of wire to disable speech in Fleet Air Arm use (see AP1186 Section 1, chapter 5, paragraph 93).

However, there is a question mark over the radio "fit" the Roc eventually ended up using in service. A diagram in AP1571A, the airframe maintenance manual for the Roc, shows the interior of the aircraft and the simple outline of the radio and its dials looks nothing like the R1082/T1083. It does have a closer resemblance to the TR9, the combined transmitter/receiver radio used by Spitfires and Hurricanes in the Battle of Britain and also fitted to the Navy's Sea Gladiator fighters and the diagram is actually labelled "combined transmitter receiver unit". There is also a "separate receiver unit" (see diagram below). The Roc pilot's notes also seem to read as if speech communication was possible and the cockpit diagram shows a transmit/receive control unit in the cockpit the same as that used on the TR9, the notes also refer to a "combined transmitter/receiver" when referring to the operation of this control. However it also refers to another control knob which altered the volume of a "separate receiver", this was almost certainly an R1110 homing receiver. It would certainly make sense to fit the TR9 to the Roc, it would have enabled the Roc to talk directly to their carrier or base and other aircraft, making intercepting and cooperation much easier. With the Navy having to use the TR9 on the Sea Gladiator it would make sense to fit them to the Rocs as well. However, the standard TR9 did not have an "intercom" facility, so if it was the radio equipment fitted the crew would have had to talk to each other via the Gosport tube. A later version of the TR9 set with intercom was developed for the Boulton Paul Defiant. A note in file ADM 1/10103 in the government archive at Kew has a request, in August 1940, for the Defiant's set to be fitted into Rocs to give it the intercom facility, which would seem to prove that the TR9 was certainly used by Rocs. Sqdn Leader "Nobby" Clarke's account of a combat between his Roc and a Heinkel 59 floatplane in late September 1940, specifically states he talked to his gunner via an intercom. Maybe someone out there can throw further light on the subject of the Roc's radio equipment? If so, please get in touch.

There is an excellent article on Royal Navy aircraft radio equipment at the start of the war on Matt Willis' Naval Air History website at <this link>.

Range

There is some confusion about the range of the Roc. Many books and online guides quote a figure of 810 miles, but this is simply an impossible figure for the standard Roc. The Skua had a range of some 760 miles, this was provided by fuel tanks with a combined capacity of 163 imperial gallons, this was made up of a 39-gallon tank in front of the cockpit and two side-by-side tanks of 62 gallons each between the pilot and gunner position. The Roc carried only 117 gallons of fuel, this was provided by the same 39-gallon tank as the Skua in front of the cockpit but only a single, albeit slightly larger, tank of 78 gallons behind the pilot. The extra space between the pilot and gunner was largely taken up by the radio equipment which had to be placed here to keep the balance of the aircraft within acceptable levels (on the Skua the radio equipment was carried just aft of the gunner's position). There was enough room to allow the gunner to use the escape hatch in the floor of the fuselage. So it is impossible to see how the standard Roc could have had a longer range than the Skua while carrying considerably less fuel and also weighing more (the Roc weighed 6,124 lb when empty compared to the Skua's 5,496 lb) and having the extra drag of the turret. it would seem unlikely that a standard Roc would have a range greater than 550 miles (combat radius of some 200-220 miles). However, a bulged "belly tank" of some 70 gallons capacity was fitted to at least one Roc and it would seem likely that it was the fitting of this that gave rise to the often-quoted figure of 810 miles range. However, this belly tank was by no means a standard fitment and it is not mentioned in the Roc pilot's notes. It seems likely this belly tank was only produced in prototype form following complaints about endurance from the squadrons using the Roc for defensive patrols around the naval base at Scapa Flow (see combat history below).

Above is a photo of the single Roc fitted with the "pregnant" belly bulge to accommodate an extra fuel tank to boost range.

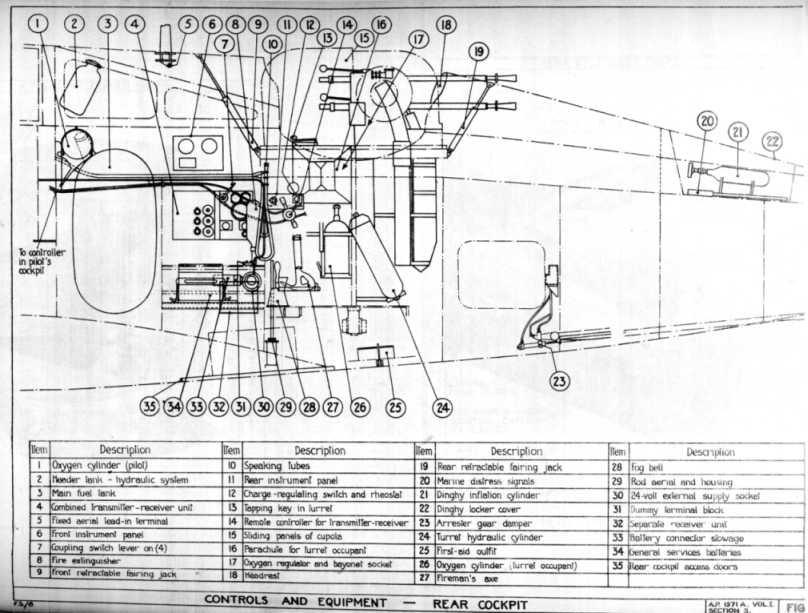

Diagram from AP1571A showing the interior of the Roc. Note the single fuel tank (3) and escape/access hatch in the floor (35), also the "Combined transmitter-receiver unit" (4), "Separate Receiver unit" (32) and the Morse code "Tapping key in turret" (13). Perhaps surprisingly it still has space for an Air Ministry "Fog Bell" (28); this handbell was to attract attention if the aircraft landed or crashed in a fogbound field, it has a secondary role to scare off inquisitive cattle! The cocking handles on each of the Browning machine guns were something that was dropped after the first few prototype Bouton Paul "A" type turrets (a single detachable cable loop was used instead). This indicates the diagram may be of an initial layout and not necessarily fully representative of production Rocs.

Made Ready for Finland

In early 1940, it was decided to give a large part of the production run (33 aircraft) to the Finns, at the time fighting the Russians. Preparations went as far as painting the aircraft ready for delivery and collecting them together in Scotland for the flight. The end of the Finnish "Winter War" stopped delivery. The Finns had a reputation for getting the most out of the assorted aircraft they operated and it would have been interesting to see what use they would have made of the Rocs had they arrived. One suspects they would have been better used as dive bombers rather than fighters. By all accounts, the Roc's performance as a dive bomber was good, and if it made its getaway flying just above the ground or sea it was a difficult target for enemy fighters to engage, and in such a fight there was at least a chance that its four belt-fed turret guns could bring down a pursuing enemy fighter.

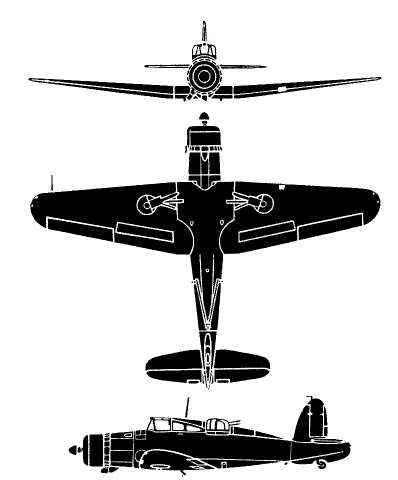

Blackburn Roc profile from wartime aircraft recognition postcard. Note it does not show correctly the "flat bottom" area or the gunner's underside hatch.

Blackburn Roc Specification

Two-seat naval turret fighter

Engine: One 815 hp Bristol Perseus XII engine (gave 900 hp plus for short bursts)

Max speed 223 mph (359 kph) with the engine on emergency power, cruising speed 135 mph (217 kph).

Range and Endurance: - The subject of controversy; see main text.

Armament: four 0.303 Browning machine guns with 600 rounds per gun housed in an electrically operated turret. Two 250 lb (113 kg) "SAP" bombs or "B" bombs or 100 lb (45 kg) anti-submarine bombs could be carried (one beneath each wing) and a standard RAF light series carrier bomb rack could also be fitted beneath each wing. Each carrier could hold 4 x 24 lb (11 kg) "Cooper bombs" or 30 Ib (13.5 kg) incendiaries.

Two-seat naval turret fighter

Engine: One 815 hp Bristol Perseus XII engine (gave 900 hp plus for short bursts)

Max speed 223 mph (359 kph) with the engine on emergency power, cruising speed 135 mph (217 kph).

Range and Endurance: - The subject of controversy; see main text.

Armament: four 0.303 Browning machine guns with 600 rounds per gun housed in an electrically operated turret. Two 250 lb (113 kg) "SAP" bombs or "B" bombs or 100 lb (45 kg) anti-submarine bombs could be carried (one beneath each wing) and a standard RAF light series carrier bomb rack could also be fitted beneath each wing. Each carrier could hold 4 x 24 lb (11 kg) "Cooper bombs" or 30 Ib (13.5 kg) incendiaries.

A factory-fresh Roc (L3084) on a test flight. Note in the top picture the projections under the fuselage, these are the forward pair of four fittings for attaching the catapult launch trolley. This Roc may have been fitted with floats for trials at Lee-on-Solent during 1940. The airframe survived the longest of any of the Rocs, being used as a static test rig for engines at Eastleigh until at least August 1945.

Flying Qualities and Equipment.

The Roc was not committed to combat in any great numbers. Probably only a dozen or so saw service at any one time with front-line combat squadrons (800, 801, 803 and 806). Although it was slower and less manoeuvrable than the Skua its wing dihedral did cure the slight instability problems suffered by that aircraft. The extra weight of the turret went some way to preventing the "nose-overs" that plagued the Skua when the undercarriage brakes were applied too heavily. The quiet Bristol Perseus XII sleeve-valve engine was very reliable³, albeit somewhat expensive. Like the Skua, it was fitted with a two-position variable pitch propeller, but of slightly larger diameter. The Roc was a simple aircraft to fly, although its huge size could be daunting to pilots at first. It had good visibility from the cockpit, essential for deck landings. It had the same dual-purpose dive-brake / flaps as the Skua and was stressed to carry out dive-bombing attacks. Like the Skua, it was fully equipped as a carrier aircraft, having an arrestor hook, folding wings, inbuilt buoyancy, and an emergency dinghy. Another feature shared with the Skua was an emergency parachute in the tail. This parachute was designed to pull up the tail of the aircraft if the aircraft entered a "flat spin" and convert it into a "normal" spin, from which recovery could be made once the parachute had been released.

Service and Combat History.

Scapa Flow

The Roc was first used operationally from October 1939 in small numbers to help defend the naval base of Scapa Flow, with 803 Squadron flying a mixture of Skuas and Rocs from the airfields at Wick and then Hatston. The presence of 803 Squadron did not stop a raid by Ju88s on 17th October which badly damaged the old battleship HMS Iron Duke. In response to this, RAF Gladiators and Hurricanes were also deployed to protect Scapa Flow and they filled the short-range "interceptor" role while the Skuas and Rocs concentrated on longer-range patrols. These missions involved long flights to cover the Home Fleet on its forays into the North Sea and to escort convoys and trawlers. It quickly became apparent that the shorter range of the Roc was a disadvantage compared with the Skua. The commanding officer of 803 Squadron requested that his Rocs be replaced by Skuas, but the request was refused. He was advised that the squadron would shortly be receiving Fairey Fulmar fighters as replacements, until then he should limit the Rocs to shorter-range patrols, so the Rocs remained on strength (803 Squadron wouldn't end up receiving Fulmars until October 1940). As the severe winter of 1939/40 turned to spring the Luftwaffe once more turned its attention to Scapa Flow, with a series of air raids on the base in March and April. By this time, Scapa's defences had been improved with radar warning and a very effective anti-aircraft barrage, and although the Germans used their fastest, most potent bomber, the Ju88, the raids achieved little besides damage and some casualties to the cruiser HMS Norfolk. During one of these raids, a Roc from 803 Squadron claimed to have damaged a German bomber. On the 12th of March, a Skua and a Roc from 803 Squadron sighted and attacked a German submarine with 100 lb (45 kg) anti-submarine bombs, forcing it to crash-dive.

Nice view of Roc L3090 with type "A" roundels on both the wings and fuselage. Notice the line where the tail assembly joins the fuselage. Production of the tail assemblies of both the Skua and Roc were subcontracted to the General Aircraft Company and brought in as complete units. This Roc served with 774 Squadron in the UK. In 1942 it was shipped to Sierra Leone in West Africa for use by 777 Squadron.

Off Norway

After the German Invasion of Norway, the aircraft carriers HMS Ark Royal and HMS Glorious hurried back from the Mediterranean. On 23rd April 1940, 800 and 803 Squadrons took 2 and 3 Rocs with them respectively when they sailed to Norwegian waters aboard the Ark Royal, (some sources say there was also a single Roc on board HMS Glorious but this is disputed). The three Rocs of 803 Squadron were launched twice on 28th April when they drove off German Heinkel He III aircraft shadowing the British carrier force. This was exactly the role originally envisaged for the Roc, although it was disappointing that the Rocs could not overtake the fleeing enemy aircraft. The newly-formed 806 Squadron was assigned a number of Rocs and took them up to Hatston, however, they did not have enough range to allow them to accompany the squadron's Skuas on raids to the Bergen and Stavanger areas.

805 Squadron was formed at Donibristle in Scotland in early May 1940 with the intention that it should become an all-Roc squadron to operate in the floatplane role against the Germans in Norway. The formation of such a unit was probably prompted by the remarkable success of "Bishop Force", a flight of six Walrus flying boats that operated out of Harstad during the Norwegian campaign. The squadron completed initial training on the landplane Roc and then moved south to Lee-on-Solent to await delivery of the floatplane conversions. With the withdrawal from Norway, there was no longer an immediate need for such a squadron and it was disbanded only a few weeks later.

Dunkirk

The next combats for Rocs came over Dunkirk, where 801 and 806 Squadrons both operated a mixture of Skuas and Rocs. The only confirmed "kill" by a Roc took place about 6.30 pm on 29th of May 1940 when a Roc of 806 Squadron piloted by Midshipman Arthur Day, with his gunner Naval Airman Harry Newton, claimed one Junkers Ju88 destroyed (it was seen to crash into the sea) and another damaged in an action in defence of British evacuation shipping. The aircraft shot down was almost certainly not a Ju88, but a Heinkel He 111 of I/KG1.⁴ A diving attack had allowed the Roc to pull up underneath the Heinkel and shoot it down using the "no-allowance" method, one witness said the bomber was " literally sawed in half..." The short range of the Roc was not such an issue for cross-channel operations and its extra defensive firepower was appreciated. In June, 50% of 801 Squadron's strength was made up of Rocs. 801 Squadron used its Rocs for dive-bombing attacks on German E-boats in Boulogne harbour on 12th and 13th June 1940 that badly damaged one boat and caused lesser damage to another two, they also machine-gunned a row of German lorries packed with soldiers. They took part in another dive-bombing attack on gun positions on Cap Griz Nez on 21st June, losing a single Roc to AA fire, its pilot Sub Lt Anthony Day and Gunner Airman Frederick Barry, being killed. Thus, by a bizarre coincidence the only pilot to be killed in combat flying a Roc, had the same surname as the only pilot to have claimed an aerial victory using a Roc. They were not the same person (as has been mistakenly claimed in online articles). Sadly Arthur "Daisy" Day and his TAG Harry Newton, who had together claimed the aerial victory, both died together only 3 months later, flying a Fairey Fulmar fighter that collided with another Fulmar when attempting to land on the carrier HMS Illustrious. For further details of Skua and Roc operations over Dunkirk see < this link>.

Rocs in flight.

The Battle of Britain and after...

During the Battle of Britain period, the units operating Rocs near the South Coast of England found themselves on the front line. This included 2AACU (Anti Aircraft Co-operation Unit) based at Gosport near Portsmouth, various Naval flights operating out of nearby Lee-on Solent and 559 fighter training squadron at Eastleigh (now Southampton airport). On the 13th of June, a Roc from 2AACU exchanged fire with an enemy aircraft. On the 12th of August 1940, a Navy Roc operating from Lee-on-Solent was surprised by a Bf109 on its tail but managed to escape by going into a steep dive and using the dive brakes to pull out low over the water (the Bf109 pilot did claim the Roc as "destroyed"). On the 16th of August, Gosport airfield was attacked by Stuka dive-bombers and two Rocs were damaged. On the 18th of August, Gosport was raided again with extensive damage caused.

The most well-documented Roc encounter with an enemy aircraft came on the 26th of September 1940 when a big Heinkel 59 floatplane was engaged and damaged over the Channel, an event fully described by Sqdn Ldr DH Clarke in the article "The Decision is Always the Pilots" in the October 1961 edition of the RAF Flying Review and also included in his book "What Were They Like to Fly". Flying with an inexperienced gunner Clarke was unable to get underneath the Heinkel, which, being a floatplane could fly along just inches above the water, meaning a no-allowance attack was impossible. Flying so low it was difficult to even bring the Roc's guns to bear, Clarke was forced to do low, skidding turns around the floatplane, trading gunfire with its three gun positions. He chased the Heinkel back to the French coast until a shortage of fuel forced him to break off the combat. Some 2 months earlier the British "Y" wireless listening service had become aware that Heinkel 59 air/sea rescue aircraft had been radioing back the position of British ships and convoys. The British had therefore warned the Germans, by a radio broadcast from the BBC, that any such aircraft would be attacked. Even so, Clarke had waited for the German aircraft to fire first before allowing his gunner to fire back.

Blackburn Roc L3085 of 2AACU, the aircraft flown by DH "Nobby" Clarke during his encounter with a Heinkel He 59 over the Channel. Notice Clarke's "saint" insignia in a diamond on the fuselage. Standing in front of the Roc is Don Sutherland who helped service the aircraft. The photo is from the Sutherland family collection. The Roc had been delivered to 2AACU on the 16th August 1940. In April 1941, it survived a collision with a barrage balloon cable, but lost its pitot tube in the process, meaning the pilot misjudged his landing and the undercarriage collapsed. It was repaired and went on to serve in the Orkney Islands, being written off after a ditching in February 1943.

During the winter of 1940-41, Rocs were sometimes used in Scotland and the north of England on ad hoc night-fighter patrols against German bombers and mine-laying aircraft. Certainly, Rocs operating out of RNAS Donibristle kept an eye out for German raiders when conducting training missions over the Firth of Forth.

At the end of August 1940, a number of Rocs were allocated to the Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF) No 110 Squadron, based at Odiham. The unit had an army co-operation role, to support the Canadian forces in the UK. It was equipped with Westland Lysanders, but after the poor showing of the Lysander during the fighting in France, the Canadians were casting about for an aircraft more suited to the role and for a while Rocs equipped one flight of the squadron. In early 1941, the squadron was renamed as 400 Squadron and began to receive the Curtiss P40 Tomahawk fighter. It relinquished the Rocs in February 1941.

The last Rocs with an "operational" combat role were those operated by 777 Squadron from a base at Hastings in Sierra Leone in West Africa. While serving as a "Fleet Requirement Unit" (FRU), it was also responsible for the defence of Sierra Leone, which became of strategic importance because of aircraft and ships staging through Freetown to supply the Takoradi air route across Africa. Five Rocs were operated by the unit, alongside two Boulton Paul Defiants and some Supermarine Walruses. Rocs were used by 777 Squadron until August 1943.

Target Tugs

From early 1941, most Rocs were used for training, many being converted to target-towing. For the target tug role the rear turret was removed and a windmill arangement installed on the port side of the fuselage adjacent to where the turret had been. This windmill could be engaged to haul in a target drogue. A rectangular box to hold the drogues was fitted under the fuselage, this could hold either two of the windsock-sleeve type drogues or three flag style drogues. The turrets stripped from them were refurbished and used on other aircraft types. Roc trainers and target tugs found their way to the Mediterranean, Egypt, Sierra Leone, South Africa, Trinidad and Bermuda. Most accounts claim that the Roc was withdrawn from service in 1943, but there are are quite a few logged incidents of Rocs still being flown in 1944, particularly overseas. For example, Roc L3176 is documented being used by 793 Squadron at Piarco in Trinidad until April 1944, and Roc L3191, also in Trinidad, seems to have only been withdrawn from use in August 1944. Likewise, L3127 and L3141 were being flown at RNAY Wingfield in South Africa in March 1944. Roc L3118 (photo further down the page) operating out of Arbroath in Scotland, was written off after loosing power and hitting a stone wall on 13th April 1944. The fuselage of Roc L3084 survived as an engine test rig at Eastleigh until 1946.

Roc target tug in Egypt, probably L3086 of 775 Sqdn at Dekheila (Alexandria).

Roc L3183, another target tug in Egypt. Again, used by 775 Squadron at RNAS Dekheila.

Roc target Tug L3100, operating from Kindley Field on Bermuda.

Roc target Tug L3100, operating from Kindley Field on Bermuda.

The use of the Roc in combat is covered well in the book "Blackburn Skua and Roc" by Matthew Willis; it includes some enlightening comments on what it was like to use the turret by ex-Roc crewman Ken Sims.

Use of Rocs as "Machine Gun Posts"

Various published sources report the bombing of Gosport prompted the stationing of 4 Rocs around the perimeter of that airbase, with the rear fuselage propped up and their turrets permanently manned during daylight hours to operate in the ground-to-air role. This would have been an understandable reaction because, after the bombing of Gosport on the 18th of August 1940, Messerschmitt Bf109 fighters flew around the base for an extended period with seeming impunity, shooting down all the barrage balloons in the vicinity. This convinced many on the base that further low-level attacks were imminent. ⁵

In 2019 a photograph of a Roc in just such an installation appeared on social media (both Facebook and Twitter). It appears genuine. However, rather than being at Gosport, it is clear this photograph was taken at the nearby Eastleigh Airfield (now Southampton Airport). Which raises various questions. Were Rocs used in this mode at both Gosport and Eastleigh? Or were the Rocs only used in this way at Eastleigh and it has been misreported as being Gosport?

Blackburn Roc used as a static machine gun post. The engine has been removed and the rear fuselage is protected by sandbags. The setting is clearly Eastleigh; in high resolution, you can see details of the terraced housing with a railway line running in front of it. The distinctive roof styles match up exactly with the houses that run along the A335 Southampton Road / Wide Lane alongside the current Southampton Airport. At the time this photo was taken the Roc would have been in a field just north of Eastleigh Airfield as it was then known. The field was used as a dispersal area for aircraft (clearly shown in Luftwaffe reconnaissance photos of the period). Southampton airport has now been extended north so that the Roc's position would now be in the middle of the runway. In the background can also be seen the factory chimney of the old Pirelli Cable Works. Eastleigh was used by both RAF and Royal Navy units which explains the sailor on top of the Roc!

While this employment of the Roc in the ground-to-air role is usually ridiculed in internet forums and articles it is worth noting that the Boulton Paul Type A turret used in the Roc was also employed on some naval patrol boats for air defence. A photograph of a Boulton Paul Type A turret on a patrol boat is featured in the book "Boulton Paul Aircraft", compiled by the Boulton Paul association. The turret was also used in an "anti-aircraft tank" prototype based on a Light Tank Mk V chassis built at the British Army's workshop at Lulworth (The light AA Tank Mk I that went into production and served with the British Army in Britain and the Western Desert featured an open turret armed with four of the Army's standard Besa 7.92mm machine guns rather than .303 Brownings). Two Beverette Mk III armoured cars were fitted with Type A turrets and handed over to the RAF Regiment for airfield defence. So it was not so unusual for the Roc's turret to be used in the surface-to-air role. In fact, a Defiant gunner (the Defiant used the same type A turret) claimed to have shot down a Bf 109 during the Battle of Britain after the Defiant itself had crash-landed and was stationary in a field! A ground-to-air engagement of a different sort!⁶ The Boulton-Paul type A turret was particularly suitable for this type of use because it used its self-contained electric motor to pressurise its hydraulic system and only required some batteries to operate, unlike other makes of British hydraulic turret that needed a running aircraft engine and pump to work. In the photo above you can see a "trolly acc" (basically a box full of batteries on wheels usually used to start aircraft engines) with a cable leading from it to a socket on the side of the Roc. This socket was a standard feature built into even the earliest Rocs, so it must have been anticipated that there would be a need to practice using the turret on the ground and it was thus an easy step to adapt it as a "machine-gun post".

Roc in Pictures

This interesting picture above shows a formation of Rocs. Note the wide difference in the type of fuselage and wing roundels. Also, note that the second aircraft has a reflector gunsight and there is a gun camera mounted in a pod near the wing root. All the aircraft carry bomb racks. It seems to have been common for the front sliding portion of the cockpit to be removed altogether (as in the 4th aircraft and the photo below). The fairing aft of the turret and the section of cockpit "greenhouse" between the pilot and turret were raised and lowered automatically to allow the turret to be rotated without obstruction, hence the difference in profile between the aircraft. The wireless aerial also "bent" with the retracting greenhouse section.

A great picture of a pair of Rocs (same aircraft as in the close-up shot further up the page). It is taken from a wartime postcard that was produced by photographic methods. The Roc was a very large aircraft, note how small the pilot looks in his cockpit.You can see the "light series" bomb rack beneath the wing and the larger rack for a 250 lb (113 kg) bomb inboard of it. The nearest Roc has the serial number L3118. Pictured here when used by 759 Squadron at Eastleigh in 1940, it later went on to serve in the Orkney Islands and mainland Scotland, being written off after an accident in April 1944.

Another Roc with a non-standard style of roundel on the fuselage.

The picture above is not of a Roc, but of the stub wings on the wheels of a Westland Lysander, however, it does show up close exactly the same type of bomb racks used on the Roc. On the right is the Light Series Carrier, able to take four light bombs, this bomb rack was also used on Skuas. On the left is the 250 lb (113 kg) rack, in this case holding a supply container. In late 1940 a number of Rocs were used alongside Lysanders by the Canadian 110 Squadron in the UK in the army co-operation role.

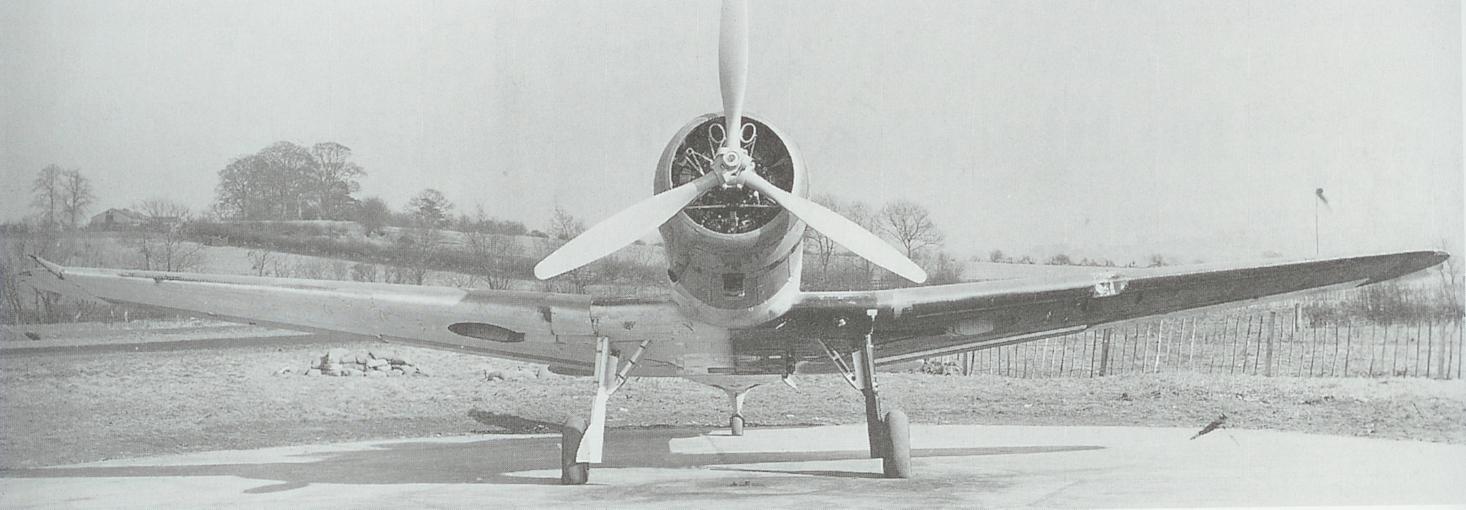

Head-on view of a Roc without the front spinner on the propeller. This picture clearly shows the two small sections of undercarriage door which flipped out at right angles to the airflow when the undercarriage was extended. It also shows well the "flat bottom" of the Roc, you can just make out the hatch in the bottom of the aircraft for the gunner to exit. The half-black/half-white colour scheme was that adopted at the start of the war to try to make friendly fighters more easily identified by the Observer Corps through binoculars at height.

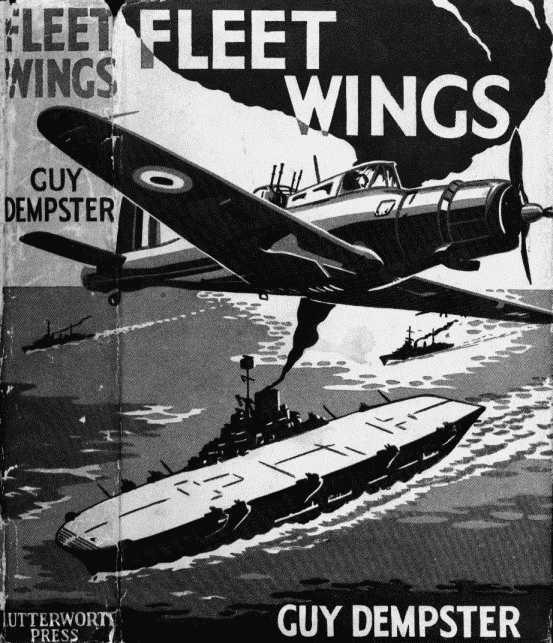

The dust jacket of this wartime boy's adventure story shows a Roc over an aircraft carrier. Many books on World War II aviation that mention the Roc, even Putnam's " Blackburn Aircraft since 1909", mistakenly state that the Roc never made any carrier flights at all, they most certainly did, and not just training flights either (see combat history above), this is confirmed in the combat reports of the squadron's involved. A photo of Roc L3062 of 803 Squadron operating from HMS Ark Royal is featured on page 57 of Stuart Lloyd's book "Fleet Air Arm Camouflage and Markings". To prove that Roc trainers also operated from carriers another photo on page 72 of the same book shows a Roc target tug on HMS Formidable. The combat reports of the various Fleet Air Arm Squadrons that used Rocs on operations are available via the Public Record Office at Kew.

Considered for Alternative Use

In October 1938, before the first Roc had flown, a meeting of the Air Council had decided that Roc production should go ahead while acknowledging that it was unlikely to be a good combat aircraft.² It was pointed out that the Roc could be used as an advanced trainer by the RAF if needed. With hindsight, it is sad that this very sensible suggestion was not carried out, and the Rocs were not handed over to the RAF "en bloc". As trainers for gunners for the Defiant squadrons and the same type of turret fitted in Halifax, Ventura and Albermarle bombers the Roc would have been very useful. It would have been ideal for use on short-range air-sea rescue duties by RAF Coastal Command, dropping smoke floats and sea markers to help rescue vessels locate downed pilots or maybe even dropping inflatable dinghies (whole squadrons of Defiants were used in this role, but not until 1942). As it was, Boulton Paul were told that production of Rocs should take priority over Defiants⁷.

Notes.

¹ The Royal Navy's doctrine that the Fleet could defend itself was flawed. The 2 pdr pom-pom and Vickers .50 calibre guns were nowhere near as deadly as was hoped (later in the war the Navy switched to the much more lethal 40mm Bofors and 20mm cannon) and the volume of fire they put up was itself a problem since under sustained attack a ship could quickly run out of AA ammunition. The 5.25 heavy AA gun was a formidable and deadly weapon, but the fire-control systems used at the start of the war proved unequal to the task of ensuring it hit its target. The Navy had expected the main aerial threat to come from slow torpedo bombers (the form of attack it favoured), and the German's use of accurate dive-bombing (first experienced off Norway) caused a rapid reappraisal of strategy. Unfortunately, when the Navy did experience the large-scale use of torpedo bombers against itself it was by the Japanese who used their revolutionary "Long-Lance" torpedoes which could be launched outside the effective range of the AA barrage. It was the arrival of radar that transformed the nature of fleet defence by fighter aircraft, making it possible to detect incoming bombers and launch high-speed single-seat fighters as a defence.

² Source for use of Roc floatplanes from Capital Ships and the decision to go ahead with production from the article "Shopping for Naval Aircraft in the Thirties" in the "Out of the Archives" section of Air-Britain "Aeromilitaria" Volume 28 Issue 109 Spring 2002.

³ The Bristol Perseus was the first sleeve-valve engine to go into quantity production. To meet the stringent tolerances required for the fit of parts the Perseus was largely hand-built with a high wastage of parts that did not conform to the required standard. This made the engine slow to manufacture and expensive to make, but it had a good reputation for reliability. With their next sleeve-valve design, the Taurus, Bristol tried to slimline the production process and subcontract the manufacture of components to aid mass production with the result that the Taurus initially had a poor reputation for reliability, something that has rather tarnished the reputation of sleeve-valve engines ever since. New methods of making components to higher tolerances came to the rescue of the Taurus and also enabled the big Hercules sleeve-valve engine to be mass-produced (although they were always more expensive than the equivalent RR Merlin). The methods pioneered by Bristol also came to the rescue of the Napier Sabre sleeve-valve engine.

⁴ Correct identification of the Junkers Ju 88 in the first 9 months of the war was hampered by a lack of good photographs of the type. The identification charts of German aircraft contained only a very crude, inaccurate representation. So it was common for the Heinkel He111 to be misidentified as a Junkers Ju 88 and vice-versa. To see an example of the Ju 88 identification silhouette available in early 1940 see this link.

⁵ In the book "So Be It!" Don Sutherland, who was based at Gosport at the time, reports that many of the personnel went AWOL after the bombing. A little-reported aspect of the Battle of Britain.

⁶ This engagement took place on 26th August 1940. The Defiant Gunner was Sgt Baker flying with pilot Sgt Thorn of 264 Squadron. The same Bf109 was also claimed by Pilot Officer Marston of 56 Squadron flying a Hurricane!

⁷ See Chapter 20, page 160 of "Boulton Paul 1917-1961- Aircraft, Projects and Studies", by Les Whitehouse, published by Crecy in 2021, ISBN: 9781910809488

Sources

A full list of sources can be found on the Skua and Roc Bibliography page.

Modelling the Blackburn Roc

If you are interested in building a model of the Blackburn Roc <This Link> will take you to a page listing the various kits that have been released over the years. <This Link> will take you to a page devoted to getting the details of building a Skua or Roc correct.

A full list of sources can be found on the Skua and Roc Bibliography page.

Modelling the Blackburn Roc

If you are interested in building a model of the Blackburn Roc <This Link> will take you to a page listing the various kits that have been released over the years. <This Link> will take you to a page devoted to getting the details of building a Skua or Roc correct.